This post is part of a series of stories and articles I wrote exactly ten years ago, on this day in 2003. This one’s a feature article based on some time I spent visiting and helping out at the Catholic Worker hospitality house in New York. For more stories in the series, click here.

30th April 2003

A young Japanese woman with purple hair tripped along First Street, clutching to her chest all the books that she couldn’t fit in her fashionably miniscule backpack. A graffiti-covered computer keyboard dangled cryptically from a lamppost. Two small dogs yapped and strained at their leashes as they passed each other, almost escaping the grip of their owners, both of whom were precariously balancing leashes, lattés and cell phones. It was a typical morning in the East Village.

For about twenty feet in the middle of the block, however, the East Village momentarily vanishes. In those twenty feet, there are no boutiques, cafes or art galleries. There are no cute little shops selling trendy knickknacks to hip Village denizens. In those twenty feet, it’s still “The Bowery.” It’s still the place where men come for hot soup, a cup of coffee, a warm place to sit, and maybe a place to stay if they’re in luck.

That small patch of First Street is home to St. Joseph’s House, a hospitality house run by the Catholic Worker movement. There have been Catholic Worker houses in this area for 70 years, ever since an ex-Communist, Dorothy Day, joined with Peter Maurin, a self-educated French peasant, to open the first one in 1933. They funded their endeavor by producing the Catholic Worker newspaper and selling it for a penny a copy. The houses have always reflected the views of their founders, fusing socialist ideology with a strong Catholic faith and a large dose of anarchism. The Catholic Worker hospitality house has persistently resisted easy definition. It gives out soup every morning from Tuesday to Friday, and yet it is not a soup kitchen. It allows homeless people to stay for as long as they want whenever there is space, and yet it is not a homeless shelter. It is vehemently anti-capitalist and most of the residents have given away their possessions, and yet it is not a commune. It has spawned 185 other hospitality houses across the country and more all around the world, and yet they are linked by no official organization. It efficiently serves soup, provides shelter, distributes clothing and produces a monthly newspaper with a circulation of 82,000, and yet it has neither a leader nor even any discernible decision-making process. It is staffed entirely by volunteers, and yet nobody calls themselves a volunteer or, worse yet, staff. Its costs spiral ever upward – the annual budget for the two New York hospitality houses and an upstate farming commune is now $500,000. Yet the price of the newspaper remains a penny a copy and it still refuses any official funding, relying entirely on 25-cent annual subscriptions supplemented by extra donations from loyal readers. Dorothy Day once wrote that she asked an ex-soldier and an ex-Trappist monk what they thought of the hospitality house after they had both been staying for a while, and was surprised by the response: “The soldier said, ‘It’s just like the Army,’ and the Trappist said, ‘It’s like a Trappist monastery.’” Others have compared the hospitality house to an Israeli kibbutzim or an Indian ashram. Day herself thought it was a pretty accurate description when she heard someone call it a “revolutionary headquarters.” Maybe it is really some combination of all of the above. Or maybe it’s just a hospitality house.

What is certain is that none of this mattered to the people lined up outside St. Joseph’s just before ten o’clock on a recent Wednesday morning. All they cared about was the food. The men stood in line – women mostly go to Maryhouse, the other Catholic Worker house on Third Street – and chatted loudly. They traded information about new places to stay and places to eat, and told stories about people they knew. One man launched into a long anecdote about his brother-in-law whose new car had been stolen and stripped for parts, demonstrating the thieves’ technique by pretending to break the lock of a car parked in the street, much to the concern of passers-by.

Yet on the subject of why they came, many were more reticent. “I been coming here for years, but I don’t know too much about the place,” said a man who was sitting with his back against the grimy brick wall, his legs drawn up and the previous day’s Daily News propped on his knees. He wore a black cap and a thick black leather jacket to keep out the slight chill of this sunny spring morning. “I just come here, get my soup and leave,” he continued, staring over the top of his newspaper at some point in the middle distance. Despite his twenty years in Brooklyn, he still spoke with a trace of a West Indian accent. Like many people in the line, he did have a place to stay, but found it difficult to make ends meet on a combination of occasional work and small welfare checks. “The people here are friendly, and they treat you with respect,” he said. “But I don’t really hang around.”

Another man added pointedly, “The good thing is, they don’t ask any questions. They don’t try to get in your business. They’ll just give you food, whoever you are.”

Nearer the front of the line, two men were comparing soup kitchens in the neighborhood. “This place is good because it opens early,” said a man with a three-inch Afro. “The Holy Redeemer, just around the corner, they don’t open until noon.” He stood in the middle of the sidewalk, away from the others who were all huddled against the wall. As he spoke, he backed off toward the curb, then pitched back towards the house, then paced up and down, forcing his listeners to keep turning their heads to follow him and also making it difficult for them to get a word in edgeways.

“Now I heard there was a bunch of Chinese people up at Grand Central, giving away fish,” he said. “Beautiful, fresh fish! Every day! But by the time I got there they stopped doing it. There were these people who’d gone up there and taken seven portions of fish. They caused trouble. Those Chinese guys were doing it for nothing, they didn’t need that. So they stopped. That’s the way it is – every time something good comes along, there’s always a few knuckleheads there to ruin it. And those Chinese, they don’t normally give nothing to you for free, at least not unless you’re Chinese. You try going into one of those places in Chinatown as a black man and see what you get.” A few heads turned towards the gray-haired Chinese man in the line, but he kept his head studiously buried in his newspaper.

“The Bowery Mission is good,” an elderly man interrupted.

“But they make you sit through a half-hour sermon before you even get any food!” shouted the man with the Afro, throwing his hands in the air and almost toppling into the street.

“That’s OK with me,” said the older man quietly. “Nothing wrong with hearing the Word of God.”

He tried to continue but was drowned out by a sudden roar from the man next to him: “Get the fuck away from those packages!” All heads turned to the front of the line, where a UPS delivery man had left a stack of packages unattended while he disappeared inside St. Joseph’s to deliver a large cardboard box with the slogan “From a small farm with love” printed on the side. One of the men had left the line and sidled up to inspect the boxes, but quickly moved away when he was noticed.

“Something wrong with him,” muttered the man who had caught him. “Seems like he wants to go right back to jail.” He coughed loudly and spat a large globule of mucus onto the sidewalk. “Been sick as a dog lately,” he complained.

“Nothing wrong with me,” the man with the Afro said cheerfully. “Never get sick, even in winter. I think it’s this thing,” he continued, pointing to his hair. “Keeps me warm. I know a brother who shaved his off after twenty years, went completely bald. After a few weeks he got sick. The doctor said to him, ‘What the hell do you expect? You been walking around with that hat on for twenty years! Your body got used to having it there.’” The men around him doubled up with laughter, guffawing until they were out of breath. Then they started to argue about the amount of body heat you lost through your head – was it 70 or 80 percent?

Suddenly the conversation stopped. A smell of soup wafted out of the open window, and the line went dead silent. The Chinese man folded up his newspaper. People toward the back of the line began shuffling forward. Soon the whole line burst into spontaneous yet subtle motion, as people tried to jockey for position without overtly jumping the queue.

The blue door swung open and there stood Haitian Gene, his massive frame filling the doorway. He stood barring the entrance for a few seconds, then stepped aside and counted the people as they surged through. Today was a quiet day, so there was space for everyone, either at the six long tables or on the bench by the front window. Gene, called “Haitian Gene” to distinguish him from another Eugene who lives in the house – the use of surnames would be unthinkably formal – wandered off with the New York Times under his arm and a cigarette behind his ear. He reads the Times from cover to cover every single day and can talk about any topic under the sun. As with many other residents and guests of St. Joseph’s, however, hard years on the streets have combined with drugs to take their toll on his body. He shuffles rather than walks.

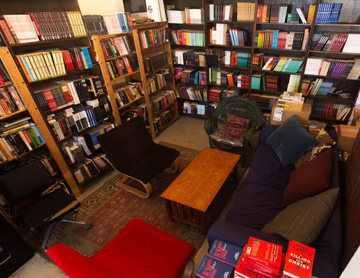

As Gene tramped off to read his paper, the last of the men went into St. Joseph’s. Their soup was already waiting for them on the tables, along with two slices of bread and a cup for tea or coffee. Rock music blared from the radio, and the sun streamed in through the frosted glass. Although the room was kept meticulously clean by mopping and scrubbing after every meal, it was still an old townhouse and the daily wear and tear from running a soup line was clearly visible. A large hole in the ceiling revealed rotting floorboards, and chunks of plaster occasionally dropped onto the tables below. The pots were dented and some of the cups were chipped, the tap dripped and one of the windows was held together with brown tape. But there were no complaints about the quality of the food. At the far end of the room stood four or five people in aprons, clustered around a massive aluminum vat which brimmed with hot lentil soup. A couple of them lived in the house, and the rest were volunteers who came in to help with the morning soup line. They all chatted cheerily as they passed out coffee, cleared up empty bowls and wiped down the tables for the next visitors.

At the sink stood Gregory, the only non-resident who volunteers for the soup line every single day. He works for a small pro bono law firm handling housing cases, and his bosses allow him flexible hours. He usually stays at St. Joseph’s until after midday, and has to make up the time by working late into the night at his job. He then wakes up early in the morning to get from his Queens apartment back to the Lower East Side in time for the soup line. His parents used to read the Catholic Worker newspaper when he was young so he always knew about the hospitality houses, and decided to volunteer about eighteen months ago. His reasons for coming so often are simple: he believes in what he is doing and he enjoys doing it. Although he doesn’t want to live at St. Joseph’s because he would have to give up his job, he loves spending his mornings there. Since George Bush came to power he has found himself increasingly troubled at the direction in which the country is going, and he finds solace in a community of like-minded people. “Now especially is a time when community is very important to me,” he said.

Behind him, a young woman with long dark hair in a pony-tail down to her waist stood watching in amazement as the chaotic activity around her somehow resulted in meals being served and tables being cleared. This was clearly her first day. She tried to help, but everything was happening too fast. She reached for a bowl of soup, but it was whisked away. Before she could pour the coffee, it had already been poured. Eventually she offered to take over from Gregory at the sink. Her name was Elizabeth and she was a graduate student in literature at New York University. She found out about the Catholic Worker when she went to confess her sins and was told to read Dorothy Day’s Loaves and Fishes as penance. “I was kind of inspired by it, and so I came down,” she said as she now mechanically passed the cups and bowls through the same routine – rinse, wash, rinse, dry, stack. She said she liked the directness and commitment of the book, and the fact that the Catholic Worker seemed to practice what it preached.

At 11:30 the soup line finished and everyone moved out to the back yard to relax and smoke. They sat around on upturned milk crates in the cramped concrete yard, chatting in the shadow of the five-story red-brick townhouse that is home to about half a dozen Catholic Worker volunteers and 20 other residents. Soon the talk turned to Luis, an 18-year-old soup line volunteer who is planning to become a Jesuit. He looked embarrassed as people began to ask him about celibacy. “Been doing a lot of handstands lately?” asked Joe, a former volunteer who now works at a day-care center. “It helps with the celibacy – makes the blood drain from your testicles,” he explained. After the jokes were finished, though, people congratulated Luis on his choice. Even Joe admitted that he would like to have been celibate himself. “Sometimes I think if I hadn’t been brought up Catholic, I might have been able to do it,” he mused.

At that point Elizabeth came out to say goodbye, and thanked Gregory for giving up his regular spot at the sink. After she left, Luis said, “Hey Gregory, I think she likes you.”

“Yeah, she even wore my gloves,” Gregory replied.

“It’s official, then,” said Luis. “You’ll have a joint bank account soon.”

The conversation continued in the cold, dark yard, and more people arrived. Janellah, who lived at the house for a couple of years after graduation, explained, “I work around the corner, so I just come by for lunch sometimes. They’ll feed anyone.” Janellah now works as an advocate for the homeless. She loved living in the Catholic Worker house, but left because she wanted to live on her own for a while. “When you find yourself fantasizing over sitting on a sofa, on your own, drinking a cup of tea, you know it’s time to get out,” she said.

Voluntary poverty, the principle espoused by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, is clearly not easy to live by. Day herself spoke of the temptations of wealth, saying, “No, it is not an easy business, this poverty.” However, it is a central plank of the Catholic Worker movement. Day’s idea was that one should not simply dole out food to the poor but should live with them and share their conditions. Or as Peter Maurin put it, “We cannot see our brother in need without stripping ourselves.” They were always careful not to glamorize poverty, making a clear distinction between voluntary poverty chosen for religious reasons and the “inflicted poverty” suffered by so many millions of people from birth. Peter Maurin saw voluntary poverty not only as the right thing for people of conscience to do, but as a way to end poverty altogether: “Everybody would be rich if nobody tried to become richer, and nobody would be poor if everybody tried to be the poorest.”

After lunch – more lentil soup – the house became much quieter. Many of the residents help out in the neighborhood by babysitting, visiting elderly people or delivering food. Some simply retreated upstairs to enjoy a rare moment of peace and quiet. Others worked on the many small repairs needed to patch up the old house. Only Eugene was left in the main room, standing in the kitchen drinking a cup of coffee. He was almost the direct opposite of big, barrel-chested, shaven-headed Haitian Gene. His gray hair straggled over his ears, and although he was by no means short, his stooping gait made him appear so. Whereas Haitian Gene moved slowly and spoke very little, Eugene was a bundle of nervous energy, pacing up and down and gesticulating wildly as he spoke in an avalanche of words. After gulping down several cups of coffee in quick succession, he invited me to go out and pick up food with him, and we set off with two shopping carts, chatting as we trudged through the chilly streets.

Eugene explained that he lived in Queens for 50 years, but that when times were bad he would always cycle over the bridge to come to the soup line at the Catholic Worker. The first time he did this was in 1977. Five years ago, he lost his job and his place in Queens and asked to move in. At first they said they were full – with only 26 dormitory-style beds in the house, space is always a problem – but eventually he was able to move in. Like all residents of Catholic Worker houses, Eugene will be able to stay for as long as he wants and receives free food and shelter plus $20 per week in “ice cream money” to cover emergency needs. The only rule is that those who are able must contribute in some way to the running of the house. Eugene’s main task is to collect food.

And collect is what we did. After a brief stop to pick up unused milk from a local Catholic middle school, we went down on to Cabrini Medical Center to gather packages of food that were past their use-by date. Eugene was well known everywhere he went. People on the Bowery greeted him as he passed, and at the hospital he stopped off for a cup of coffee and a chat with the nutritionist and some of the administrators. The shot of coffee fueled another stream of conversation, mostly about old movie stars. It was enough to carry us back to the Catholic Worker to drop off the food. “Any coffee on?” Eugene shouted as he rushed through the door. The few people who were now scattered around the main room smiled at the familiar refrain. Patience for people’s idiosyncrasies, it seems, is a crucial part of communal living.

As the afternoon wore on, some of the residents started preparing a huge pot of pasta for dinner. Others were lucky and had the night off. One of them was Jim, a 51-year-old ex-musician and ex-priest. Over a cigarette in the back yard, he explained that one of the things that attracted him to the Catholic Worker was the concept of voluntary poverty, difficult as it is. For him, the hardest thing was giving away his collection of 2,000 LPs. He still sometimes forgets that he has given them away, and starts saying, “I have this great record. . .” But he knows that even his LPs are not really that important. He said his spiritual teacher once asked him, “What is essential to you having joy in your life?” The teacher defined joy not as temporary happiness, but as long-term spiritual wellbeing. Jim said he thought about it for a long time and realized there wasn’t much. Telling this story now in the fading light and increasing cold of the St. Joseph’s back yard, he stopped and looked down at the ground, a little embarrassed. “To be honest, if someone was telling me this shit, I’d say, ‘Take it home!’” he said sheepishly. “But I’m just telling you the way I see it. I know it sounds corny.” He paused for a while, then looked me straight in the eye and said, “Doing the soup line gives me that joy. I don’t know why, but it does. I feel like now at 51 I’m right where I should be. I’m where I should have been since I was 18, although at the time I wasn’t ready for it.”

Jim found that the people with the most to give were the people with the least material wealth. “I don’t know why, but it seems to work that way,” he said. “When you have things you seem to cling onto them. When you don’t, you realize you don’t really need them and it’s easier to give up whatever you do have.” Apart from the basic necessities of food and shelter, he said that everything else is unnecessary, and that the only important thing is to provide the necessities for those who don’t have them.

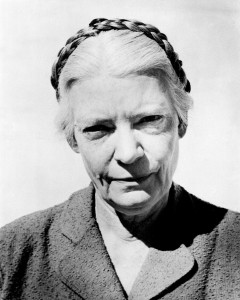

Jim’s ideas, like everyone else’s in the house, are heavily influenced by Dorothy Day. Indeed, Day’s presence is everywhere, from the photos on the walls to the everyday conversations – ask a Catholic Worker what they believe, and the response will often begin, “Well, Dorothy used to say. . .” There is even a small room at Maryhouse dedicate to her memory, containing an ever-burning candle and the table on which her body was laid out after her death in 1980. Her personality so dominated and shaped the movement that many wondered if it would survive after she died. It has not only survived but thrived, not by transforming or looking to new leaders but by operating almost as if Day were still alive. Its members seem to use “what Dorothy would have done” as a guide both for their own lives and for the direction of the Catholic Worker. To introduce yet another paradox, it is a progressive movement based on tradition. It is not tradition in the sense of a blind adherence to the past, but more like G.K. Chesterton’s definition: “Tradition is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who are walking about.” Maybe a democracy of the dead is the closest thing the Catholic Worker has to a system of government.

A common set of beliefs also binds the movement together. Because of its anarchist roots, there is of course no complete commonality of views. Maryhouse on Friday nights hosts discussions on both religious and political issues, and the debate can be quite vigorous. But war is one thing on which there is no difference of opinion. The Catholic Worker has always been strictly pacifist – many of its members were jailed for draft resistance during World War II and the Vietnam War – and it remains so today. Somebody once described the Catholic Worker as “the only soup kitchen that has a foreign policy.”

That foreign policy is on display every Saturday morning at Union Square, as residents of St. Joseph’s and Maryhouse join up with members of the War Resisters’ League for the peace vigil that they’ve held every Saturday since Sept. 15, 2001. There were about a dozen of them on a recent Saturday, clustered around Abraham Lincoln’s statue holding large banners. It was the first weekend in a long time that the sun had been out, and over the two hours their numbers got up to about 20. At the height of the resistance to the invasion of Iraq, there had been almost 100. The largest banner read, “Terrorism is only increased by more terrorism.” Another displayed a quote from novelist Barbara Kingsolver: “What I want is so simple I almost can’t say it: elementary kindness. Enough to eat, enough to go around. The possibility that kids might one day grow up to be neither the destroyers nor the destroyed.”

A young woman strolling in the park with her boyfriend stopped to read the Kingsolver quote. She finished it, thought for a moment, then curled her lip and said, “Whatever. It’s over. The Iraqi people are free now.” She turned and walked away, linking arms with her boyfriend and pulling him close to her.

The man holding the banner shouted after her that the Iraqi people were not in fact free, but she was gone. He sighed and smiled in resignation. It was the only negative comment of the day, so he wasn’t doing too badly. His name was Paul Stetzer and he was a retired science teacher; neither a member of the War Resisters’ League nor affiliated with the Catholic Worker. “I’m just a guy who shows up sometimes,” he said with a shy smile.

On the other side of Abraham Lincoln stood Carmen Trotta, a member of both groups. He was busy explaining to an old man nearby how to handle a court appearance. They had both been arrested on Good Friday with 22 others for boarding the USS Intrepid aircraft carrier after the Stations of the Cross procession across Midtown. “You could plead guilty, but then you have to pay the court fee,” said Trotta in the bored voice of someone who has been arrested many, many times. “That can be up to $60.”

The old man, whose name was Sam, looked nervous. He was not used to being arrested; it was only as the assault on Iraq intensified that he felt motivated him to take action. “I never took part in these civil disobedience acts before,” he said. “I never wanted to. But with things the way they are, I just felt it was something I had to do.”

In spite of the Catholic Worker movement’s strong activist element, it is not a political organization. Its co-founder Peter Maurin was suspicious of organizations, writing, “If the best kind of government is self-government, then the best kind of organization is self-organization.” He believed in personalism, by which he meant taking personal responsibility for achieving social change, living out one’s beliefs rather than simply joining a party. The personalist concept, which still guides the Catholic Worker today, is akin to the idea Gandhi expressed in his famous line, “Be the change you want to see in the world.”

The people at the Catholic Worker house live out their beliefs every day by serving soup, handing our clothes, giving shelter and opposing war. They often find themselves aligned with leftist groups, and indeed Peter Maurin advocated “Christian communism,” but the Catholic Workers are inspired by a much older text than the Communist Manifesto. Their convictions come from a very simple reading of passages in the Gospels such as, “Whatever you did unto the least of these my brethren, you did unto me.”

They are not heroes or saints, as some would have it – they still laugh about a gushing New York Times profile of them a few years ago that was headlined “The Givers.” Nor are they bizarre eccentrics trying to reconcile the irreconcilable, as others have labeled them. They are just ordinary people trying to live according to their conscience in a society in which it is increasingly difficult to do so. They are simply Christians trying to live according to the Gospels, following what Peter Maurin described as “a philosophy so old it seems like new.” They have given up some of the luxuries of life so that other people may enjoy some of the basics. Maybe the fact that this is so unusual says more about us than it does about them.

There are 9 comments

This was a great article. I had heard about the Catholic Worker movement but only knew a little bit about it. In my opinion, it does seem to mesh with the views espoused in the Gospels.

Thanks Brian, glad you enjoyed it! It’s strange that living in a manner consistent with the Gospels is so rare. I suppose it’s difficult to do in the modern world, but I liked their honesty and determination.

Thanks for this wonderful article, Andrew! I haven’t heard of Dorothy Day and her movement before. It was very inspiring to know about her and about the Catholic Worker movement. I want to read her book ‘Loaves and Fishes’ now. I am loving this series ‘Ten Years Ago’ 🙂

Yes, they’re not very well known. Loaves and Fishes is a fascinating book. It’s a shame – I just gave the book away, and would have sent it to you if I’d known. Anyway it’s quite old, but I’m sure you can find a second-hand copy somewhere. Glad you like the series! I plan to continue it – am coming to the end of my Columbia Journalism School articles, and will be starting on Wall Street Journal soon, which will be a little different 🙂

Looking forward to it!

“If God does not build the house, in vain do its builders labour…. Those who are sowing in tears will sing when they reap” The tears of our guests are usually hidden inside their depression, but those words of Psalm 127 have been fulfilled with a vengeance recently. Ali and Jean Richard, both former long-term guests at Dorothy Day House, have both been given ‘Indefinite Leave to Remain’! Also Abukar who lived with us for two weeks, got ‘leave to remain’ two days in! Certainly a time for rejoicing!

We are a gaggle of volunteers and starting a brand new scheme in our community.

Your web site offered us with valuable info to work on.

You have performed an impressive process and our whole neighborhood can be thankful to you.

Hey – nice piece, but it is false to say that the Catholic Worker has always been strictly pacifist. This was not at all clear during the early years of the movement, and Day’s opposition to World War II was a shock to many members and subscribers. There were early Catholic Workers who left to movement and volunteered to fight for the Allies. And, if you read the Catholic Worker from the late thirties and early forties, you will find numerous essays on Aquinas and the just war tradition written by CUA’s Msgr. Barry O’Toole. (You will also find, of course, Day’s more thoroughly pacifist take on the war.) Pacifism only emerged as a central pillar of the movement during World War II. And, commitment to civil disobedience only became central later, when Day would protest nuclear attack drills during the fifties. But, something in what you say is true: since roughly the fifties, hospitality, pacifism, and civil disobedience have been central, unifying features of the movement.

Thanks very much for the comment! It’s fascinating to hear about that early history of the Catholic Worker movement. The people I spoke to for the article had joined in the fifties/sixties and later, so for them, pacifism was a central part of the movement. I know that in WW2 it was a much more controversial position, since fighting Hitler could be much more easily justified under the “just war” tradition than later conflicts like Vietnam. Didn’t know about those internal conflicts within the Catholic Worker, so thanks very much for letting me know about that. I’m glad you stopped by.