Are you responsible for the sins and failures of your adult children? If so, what do you do about it? These are the questions posed by The Sound of the Mountain, a beautifully quiet but powerful book by Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata.

Imagine you’re a parent who’s always done the right thing, lived life carefully and respectfully, had a decent job, raised a family. Then you see your children’s lives and marriages falling apart. Your son cheats shamelessly on his wife. Your daughter and granddaughter behave in ways you find distasteful.

Are you responsible for the sins and failures of your adult children? If so, what do you do about it?

These are the questions posed by The Sound of the Mountain, a beautifully quiet but powerful book by Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata, which I read for this year’s Japanese Literature Challenge.

The questions the book raises about parenting and ageing are complicated by the fact that Shingo, the main character, is not as blameless as he at first seems to be.

For example, Shingo originally fell in love not with his wife Yasuko but with her sister, and he only married Yasuko out of pity after her sister died and she became a kind of servant to her sister’s widower.

He still thinks about the sister, his first love, all the time. It goes so far that when he sees ugliness in his daughter and granddaughter, he attributes it to his original mistake in marrying the wrong sister:

“If Shingo had married Yasuko’s sister, then probably he would have had neither a daughter like Fusako nor a granddaughter like Satoko. This was hardly a proper occasion to stir in him so intense a yearning for a person long dead that he wanted to rush into her arms.”

On top of that, Shingo has feelings for his daughter-in-law Kikuko that seem to go beyond those a father-in-law should have. When the two of them meet and go walking in the Shinjuku Garden, it feels for all the world like a lovers’ assignation.

Shingo never acts on these thoughts and feelings, perhaps because of his traditional upbringing in the country, with its strict codes of morality. His son Shuichi, having grown up in the city in a younger generation, is not so tied to these codes, and so he follows through on his desires. He has an extra-marital affair which he refuses to break off even when his wife knows about it, even when her desperation at his infidelity becomes so intense that she aborts their long-awaited child.

All of these events echo through the life of the father, along with the breakdown of his daughter Fusako’s marriage and his son-in-law’s attempted suicide. People keep urging him to take action, but he doesn’t know what to do, and when he does try to intervene, he is ineffective. He takes refuge in the routine of commuting to the office every day and drinking tea and commenting on flowers in the garden. He takes refuge, perhaps, in the failures of ageing and the sympathy that his increasing forgetfulness brings him, another excuse for inaction.

This is a quiet, subtle book. Dramatic events happen, but mostly off-stage, and the main characters’ reactions to these events are muted, hesitant, incomplete. Most of the action described in the book is domestic and quotidian. It’s not a hero’s journey.

Shingo is no hero, but he’s no villain either. He’s an old man struggling to deal with the mistakes of his own life and to understand what role he should play in the lives of his grown-up children. Is his son’s infidelity an expression of his own repressed desires? Is his daughter correct to say that “you made me what I am by not liking me”?

As Shingo goes about his quiet, inoffensive life, shuttling to and fro on his commuter train and cutting back bushes in his garden to give the cherry tree more room to grow, these questions rumble in the background of the story like the sound of the mountain.

If you want to participate in the Japanese Literature Challenge or read other participants’ reviews, head over to Dolce Bellezza for the details.

You could also read my entries from last year on The Pillow Book and The Great Passage. And for another take on The Sound of the Mountain, read JacquiWine’s excellent review from a previous challenge.

There are 11 comments

I only read one Kawabata, a long time ago.

I like the sound of this one, with it’s questions about parenting. Thanks for bringing it to my attention.

It’s my first, and I’d like to try more. Which one did you read? Turns out Vishy is quite the Kawabata fan, so he recommended a couple to me. Hope you and your loved ones are doing OK amid the coronavirus outbreak <3

I’ve read Kyoto.

We’re all fine, so far. Thanks for asking. We’re stuck at home now.

We’re mostly stuck at home too – Serbia has introduced quite strict measures, even though they don’t have many cases so far. They’re trying to get on top of it and slow the spread as much as possible, which I can appreicate. I know things are much worse in France, so I hope you get through it OK and can get back to normal life and literary escapades before too long.

These are really frightening times.

I’m getting worried but so far, we’re all safe at home and don’t intend to go out, except for grocery shopping.

Take care.

I’ve only read one of his books and I distinctly remember thinking “I’m reading this on my commute on public transit in rush hour and I’m not getting out of it what I should be”. *chuckles* Ever since, I’ve meant to return and spend some time with his work, so I’ll be looking forward to more of your explorations.

Serbia seems like a decent place to be: keep well!

Haha, I know EXACTLY what you mean! I used to do a lot of reading on public transport, and what I call “quiet” books like this one would often get lost in all the noise and distractions. Some books are better when you have time and solitude. Hope you are doing OK and staying safe over there in Toronto!

I’m intrigued with your description of the book. With many of the dramatic events you detail in your review, it seems impossible that it is a quiet book. I definitely want to check this one out now!

Yes, it’s an interesting book in that way, Lisa. So much drama, and yet so restrained in the telling.

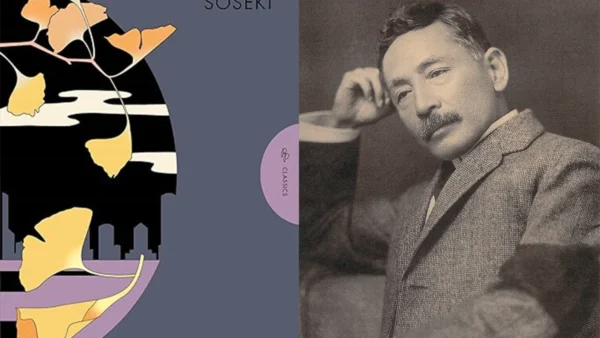

Lovely review, Andrew, and many thanks for linking to mine. I completely agree with you about the subtlety of this one. So much is repressed or lefty unsaid. Have you read Soseki’s novel The Gate? if not, you might find it of interest as there are similarities with the Kawabata.

Best, Jacqui

Hi Jacqui, Thanks for the recommendation! I haven’t read that one, but I’d like to now. While reading about it, I saw that it was part of a UNESCO project to translate masterpieces of world literature, and I spent a happy half-hour or so exploring that list as well 🙂