The eggs of the spot-billed duck. Shaved ice with a sweet syrup, served in a shiny new metal bowl. A crystal rosary.

These are just a few of the items on a list of “refined and elegant things” in the Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon. Then there are “things that make your heart beat fast”, “things that make you nostalgic”, and, on the other hand, “infuriating things” or “things later regretted”. And, beyond the lists, there are anecdotes, jokes, improvisational poetry competitions, and some quite beautiful observation of life.

One of the things I love about reading is the way it transports me to other places and times and lets me live a little in other lives very different from my own. And I enjoyed this journey a thousand years into the past, as part of Japanese Literature Challenge, to spend some time in the very congenial company of Sei Shonagon, a lady at the court of the Japanese Empress.

The Wonders of Chinese Poetry Gymnastics

Sei Shonagon is good company for several reasons. First, she has an encyclopaedic knowledge of Chinese poetry and is able to deploy it wittily in day-to-day life to do everything from winning an argument to telling a joke to making an appointment.

Sometimes the off-the-cuff puns and wordplay ping back and forth between the characters, with each one picking up on the other’s allusions and taking them further.

When someone steals cherry blossoms from outside the palace window at night, Shonagon makes a subtle reference to “someone who’d come there ‘still earlier than I myself’,” alluding to a line from a tenth-century Tadamishu poem while also indicating that she had witnessed the blossom theft.

The Emperor then picks up on the allusion and asks “Who else would have ‘come to it’ and seen the blossoms” (another line from the poem), and the Empress replies with a smile that “Shonagon ‘blamed the spring winds'”, another allusion to another poem that the Emperor then quotes from at length.

I have always wanted to be able to do things like this! So watching Sei Shonagon and her fellow courtiers in action was literary wish fulfilment for me. In reality, although I read quite widely, I recall very few details, and what I do recall always evades me at the relevant time. So I end up saying something like, “Oh, it’s like in that book, erm, you know, by that German author, when she says something like, well no, that’s not quite right, oh, I’ll have to look it up, but you know what I mean.”

The Importance of Paying Attention

Another reason why Sei Shonagon is good company is that she is a keen observer and shows the importance of paying attention to the best of life. To take just one among literally hundreds of examples:

“It’s beautiful the way the water drops hang so thick and dripping on the garden plants after a night of rain in the ninth month, when the morning sun shines fresh and dazzling on them. Where the rain clings in the spider webs that hang in the open weave of a screening fence or draped on the eaves, it forms the most moving and beautiful strings of white pearly drops.”

Descriptions like this occur throughout the book—so often, in fact, that the translator Meredith McKinney says she had to vary the wording to avoid sounding too repetitive in English. For the single Japanese word okashi, she uses mostly “delightful”, but also “charming”, “lovely”, etc. Even with that variation, there are still a lot of “delightful” things in The Pillow Book.

At first, I saw this as a flaw in the book. The turn of the first millennium was a time of great upheaval at the Japanese court, full of political intrigue and power struggles, many of which affect the Empress quite profoundly during the time period covered by the book. How could Shonagon ignore all of this and tell us instead about the delightful way in which the buds of the peach trees lie cocooned in their sheaths like silkworms? It seemed like what we would today call avoidance or denial.

Then I realised that there’s something very deliberate and wise about the way Shonagon chooses to pay attention to what’s right in front of her instead of the power struggles over which she has no control. It seems like a good prescription for life. The court may be in turmoil and the Empress’s position may be increasingly insecure, but isn’t it delightful to see the richly-coloured red leaves of the Chinese hawthorn showing so unseasonably in the spring green? And look at the charming cat with a white tag on her red collar, walking along by the railing of the veranda beyond the blinds, trailing her long leash behind her. How elegant she looks!

This is not avoidance but immersion in the stream of life. It’s awareness of the present moment, and it’s also gratitude for what you have instead of rage and resentment about what you don’t. It’s something I’d like to do more of in my own life.

The Invisibility of the Poor

One downside of this approach, however, is that other things beyond courtly intrigue are also invisible. Most notably, the mass of people who had to toil and suffer to sustain this small elite in their indolence and leisure are almost completely invisible.

This is a problem I encounter in most accounts of aristocratic luxury, and it’s present here too. On the few occasions when the ordinary people are not ignored, they are deeply patronised.

When the ladies decide on a whim to build an enormous snow mountain, it’s the servants who have to come from their homes and shovel all that snow, with the threat of having three days’ pay docked if they don’t come. Shonagon lays a bet on how long it will last and has the gardener guard it day and night to make sure nobody walks on it and damages it. But the Empress sends her own servants to destroy the mountain to play a trick on Shonagon, and they force the gardener to keep quiet about it “on pain of having his house destroyed.” All of this is presented as great fun.

On another occasion, on a poetry-writing trip to the countryside, the ladies come across some peasants milling rice and laugh at how unfamiliar it all is. In a list of “frustrating things”, Shonagon complains about people who talk about another person when that person is within earshot, adding:

“This is very embarrassing, even if the person concerned is a mere servant and not someone of consequence.”

It’s not fair, of course, to expect an aristocratic writer from a thousand years ago to be socially progressive. Sei Shonagon’s attitudes reflect the society in which she lived, a rigidly hierarchical society in which officials of the fifth rank look down on those of the sixth rank and those of the sixth look down on those of the seventh. The fault is with the society more than the book, but it still grated on me at times.

Immersion in Another World

Anyway, a third reason why Sei Shonagon is such good company on this tour through 11th-century Japan is that she is a meticulous observer and recorder, not just of details but also of characters and social dynamics. I developed an extensive picture of what life was like for her and her fellow courtiers, and inhabiting that world for a while was a treat for the imagination.

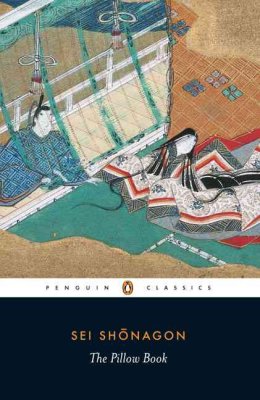

For those who are interested, there are extensive footnotes (at least in my Penguin edition), explaining exactly who each person is and how they relate to the others. I dipped into some of these but skipped many of them. This is not a book in which you need to keep flipping to the footnotes to understand what’s happening. You can enjoy it without any notes at all; the notes simply give extra depth for those who are particularly interested.

One thing to be aware of is that The Pillow Book is fragmentary. It consists of short chapters devoted to separate incidents, observations or lists, and the chronology is all over the place. There’s no coherent story to follow, and you shouldn’t read it expecting a sense of progress, resolution, or character development.

Read The Pillow Book, instead, for a steady accumulation of delightful details and witty observations. Read The Pillow Book to feel for a few hours as if you live in 11th-century Japan with an erudite, eloquent, snobbish but entertaining companion to guide you through it all. Read The Pillow Book, also, to remember that no matter what else is happening and what regrets and worries you may have, the here and now is often quite delightful.

What Do You Think?

I read The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon as part of a readalong for the Japanese Literary Challenge. You can read other bloggers’ thoughts here:

I’d love to hear your thoughts on The Pillow Book, so please leave a comment below!

There are 10 comments

Great commentary Andrew. Though I have not read it myself, The Pillow Book has been on my radar for a long time. I think that the idea of dealing with the day to day issues of life over the “big stufff” is a common issues for humans that goes back a long ways.

Thanks Brian! Yes, you’re right—the Tao te Ching was talking about this 4,000 years ago. But sometimes I think it’s good to get a reminder. Not that we have to avoid the big stuff, but just remember the present moment as well. Hope that this post made The Pillow Book bleep a little louder on your radar 😉

This sounds so delightful! 😉 Seriously though, I think I have had this book on my shelf for a very long time. I like what you say about how she reminds about being present and grateful and not railing against the things you cannot control. Seems like a good lesson for the times we live in today too. I will get around to reading this someday!

Haha, yes, delightful indeed! I think the balance between engaging with the world and being overwhelmed by it is a tough one to strike, and with things the way they are, paying attention to the present moment seems like a good policy.

Andrew, I read your review the first day you published it, and I have come back to read it several times since. Your ability to write about books astounds me; you pierce through to the hidden elements as easily as the important (more obvious) ones. I appreciate how you highlight background information, or make connections for us, so beautifully that I wonder how I’ve missed it in my reading through, and I feel compelled to return to the book for a reread. Thank you so much for being a part of the challenge, for writing brilliant posts, and adding to my reading experiences. I will link to this in my Sunday wrap up post.

Wow, thank you so much, Meredith! As it happens, I love the way you write about books, so this praise means a lot coming from you. I think that one of the wonderful things about book blogging is that you realise how different people read the same book in different ways, and I love discovering the ways in which other people see things that I’d missed.

I really enjoyed the challenge, and speaking of missing things, I’m wondering how I’ve managed to blog for all these years without being aware of it and joining it before. Anyway, thanks for organising it, and I’m already looking forward to next year and adding books to my TBR list 🙂

Hahaha: how I do relate to your “but you know what I mean” scenario.

You raise any excellent point about the class issues lurking behind this book. I’ve read about this volume before but I don’t recall having that pointed out previously. The snow mountain story is delightful, until you think about the servants having such a strain placed on them, in service of that delight. Rather like the point raised by Jo Baker in Longbourne about the Bennett’ sisters’ muddy clothing after all those “romantic” walks in the country.

Ah, I’m glad I’m not the only one 😉 That’s why I like writing—I get to herd my thoughts together in a way that never seems possible when I’m talking.

I haven’t read Longbourne, but yes, I’m sure the servants would have had a very different perspective on what’s romantic! It’s a tricky thing for me as a reader—I don’t blame Sei Shonagon any more than I blame Jane Austen for reflecting the class attitudes of their time and position. But I do feel the absence of that other perspective when I’m reading about the activities of a small minority.

Beautiful review, Andrew! The Pillow Book is one of my favourite books. I keep going back and reading my favourite passages and lists again. Glad you liked it ? Thanks for sharing your thoughts ?

Thanks Vishy! I enjoyed it too, and I’m glad your post prompted me to remember some of the things I liked about it. Might be time for a reread 🙂