I’ve read gulag memoirs before, but Shadows on the Tundra affected me even more deeply than the others—perhaps because of the age of the narrator, or perhaps the Lithuanian history that I didn’t know before, or perhaps just the stark horror of the scenes that Grinkeviciute depicts, combined with nostalgic glimpses of life back home, when her giddy innocence reminded me of Natasha in War & Peace.

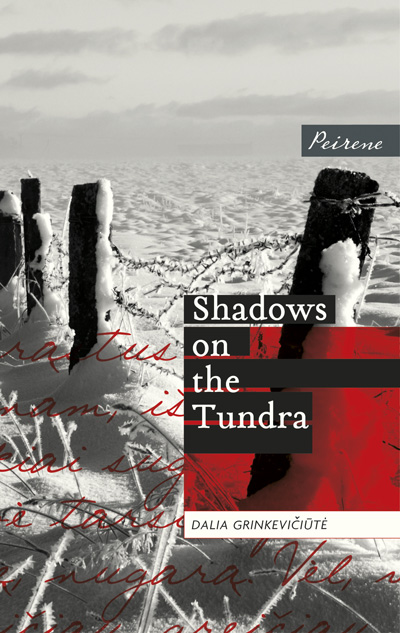

The story of how Shadows on the Tundra came into existence is almost as amazing as the book itself. As a 14-year-old girl, Dalia Grinkeviciute was deported with her family from Lithuania to a Siberian labour camp. Seven years later, in 1949, she escaped home and wrote her memoirs on scraps of paper which she buried in a jar in the garden to keep them safe from the KGB.

But then she was arrested again, and when she returned years later, she couldn’t find the jar. Only in 1991, after Grinkeviciute’s death, was the manuscript finally discovered and published. It went on to become a Lithuanian classic, and the original handwritten copy is now housed in the National Museum in Vilnius.

The tale itself is brutal. Shadows on the Tundra starts with a seemingly never-ending journey on trains, buses and boats across the USSR to the Arctic coast in the far north of Siberia. The conditions are unbearably cramped, food is scarce, but soon things get much, much worse. The 450 Lithuanian deportees are deposited in the uninhabited tundra on the shore of the Lena river with some wood, bricks and other basic provisions and are put to work building the barracks that will house them through the long Arctic winter.

The senselessness of it all is astonishing. They work long, sixteen-hour days of manual labour in sub-zero temperatures for a small ration of bread. Soon the snow comes, so deep and thick that their barracks are buried in it, and they have to dig out a tunnel from a window to reach the outside world. No heating is provided, but when they “steal” firewood from the state’s ample supply, they are arrested and punished.

Unsurprisingly, people start dying at a horrifying rate. Starvation and hypothermia are obvious dangers, but diseases like scurvy and dysentery are also rife. They could be cured easily with just a slight improvement in diet, but instead the bodies are piled up in the snow. An Arctic winter is also completely dark, of course, so the horror of this life is hard to comprehend. It’s a miracle that anybody survived.

Throughout Shadows on the Tundra, Grinkeviciute never explains the reason for this brutal punishment. Only in the Afterword are we told that it was part of Stalin’s mass deportation of the political, economic and cultural elites from Lithuania and neighbouring Baltic states as a way of exerting control. The whole project is senseless. Later in the book they begin canning fish, and they continue even after the fish have rotted—the impossible targets simply have to be met.

Amid the horror, there are poignant glimpses of Dalia’s normal life back home only a few months earlier.

“I was taking a shortcut through Vytautas Park and about to skip down the steps, when suddenly I stopped dead in my tracks, entranced by the sight before me. The sun was golden, the city aglow at my feet, the air smelt of blossoms. For the first time in my life, my heart throbbed with the joy of springtime, which was my springtime too. I took a deep breath, closed my eyes and felt incredibly happy. ‘Ah, life, how splendid you are. And youth—how splendid too! What a joy to be alive!’ My eyes, wide with excitement, welled up with tears of adolescent bliss and I headed full tilt down the hill, drawn by the siren call of the theatre, of music and the rapture of young life.”

I’ve read gulag memoirs before, but Shadows on the Tundra affected me even more deeply than the others—perhaps because of the age of the narrator, or perhaps the Lithuanian history that I didn’t know before, or perhaps just the stark horror of the scenes that Grinkeviciute depicts, combined with these nostalgic glimpses of life back home, when her giddy innocence reminded me of Natasha in War & Peace.

My only disappointment was that the story ended in 1943, with Dalia still marooned in the Arctic, shivering in a small yurt where “a piercing wind was blowing in from the sea and the waves were crashing madly against the shore.” I wanted the impossible—to know about Dalia’s escape, her life in hiding back in Lithuania, being arrested again and then, much later, trying to put a life together from the ruins of her youth.

But she didn’t get a chance to tell that story. What we have is a fragment, but it is a powerful and important fragment. It’s a story of survival in the harshest circumstances, of the kindnesses and cruelties that come out in those circumstances, of human nature at its worst and best. It’s a story I’d recommend to anyone.

If you enjoyed this post, please check out more of my book reviews, or sign up for my free newsletter.