Click here to find out what people are saying about On the Holloway Road.

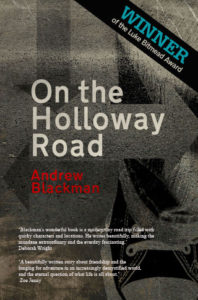

My debut novel On the Holloway Road (Legend Press, February 2009) won the Luke Bitmead Writers’ Bursary and was shortlisted for the Dundee International Book Prize.

The book is available in branches of Waterstone’s, Borders and other UK bookshops, and can be ordered online from Amazon, Waterstone’s, WH Smith and other booksellers, or direct from the publisher, Legend Press.

It is also available to download as an eBook from Waterstone’s or on Kindle US/UK.

It tells the story of two young Londoners who, inspired by Jack Kerouac’s Beat classic On the Road, embark on a similar search for meaning and freedom in modern-day Britain. Along the way they listen to a scratchy old cassette recording of On the Road, and find their journey consciously and unconsciously mirroring that of Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty. They discover, however, that the horizons of 2008 Britain are considerably more limited than those of 1950s America, and their attempts to lead a spontaneous life are dogged by speed cameras, policemen, traffic wardens and CCTV.

A beautifully written story about friendship and the longing for adventure in an increasingly demystified world, and the eternal question of what life is all about.

Zoe Jenny

Blackman’s wonderful book is a modern-day road trip filled with quirky characters and locations. He writes beautifully, making the mundane extraordinary and the everyday fascinating.

Deborah Wright

There are echoes of Jack Kerouac in this freewheeling adventure down the CCTV-ed, drizzly corridors of modern Britain. But really this, too, is a novel about emptiness and failure, and an inability to engage. It’s not the most cheery read, but it does have some glorious sprees.

Daily Mail

‘On the Holloway Road’ follows Jack and Neil on what should be a journey of discovery and adventure. Their journey is punctuated by a host of minor characters, skilfully depicted by Andrew Blackman, who manage to consistently disappoint two travellers who are deliberately looking for more than they will be able to find.

Notes from the Underground

Here’s a very short extract:

I first met Neil not long after my father died. I was living in a big old red-brick Victorian semi in north London with my mother and her vicious cat Sparky, trying and failing to finish a long, learned novel packed tight with the obscure literary allusions and authentic multicultural credentials that the publishers loved in those days. Then out of nowhere Neil rode into town, all bravado and muscles, shaved head and mad, staring eyes. He was still just a boy, really, but a boy with an ASBO at fourteen, a caution at fifteen, a spell in junior detention at sixteen and with a boy of his own by seventeen. He was a boy who was wild, dangerous and soft-hearted, a boy who read Nietzsche one minute and manga the next, a boy who wanted to learn everything, see everything, do everything, a boy who wanted to live more badly than anyone else I knew.

Compared to my own sad, shambling existence in the shadows of life, his was a kaleidoscope. I peeped from behind my mother’s curtains at the world outside and wrote about people like Neil. I never believed that he really existed until I met him.

Here’s how it happened. It was one of those long, cold winter evenings in London, when the streets are slick with a rain you don’t recall having fallen and the lights are an orange ball above you in the damp, black chill, fighting feebly against the night. Water hangs in the air with nowhere to go and as you brush against these tiny cold needles they stab your face, making you draw your hood closer about you. Long, dark alleyways harbour thieves and villains, furtive drug-dealers, nervous knife-wielders and young drunk couples rutting. Through it all runs the Holloway Road, a long straight road with dismal shuttered shops on either side, the gloom punctuated at infrequent intervals by the bright lights of a pub, kebab shop, curry house, burger joint.

One or two of the old fish and chip shops remain, but they are relics of a time fast being forgotten. A younger crowd roams the streets on these nights, ravenous for real red meat, big slabs of it slathered in ketchup and hot chilli sauce. Fish seems strangely genteel for such a crowd. Even an inch of grease and a side order of thick, stodgy chips cannot hide the slight effeminacy of the tender white fish that melts away at the first bite. The crowd on the Holloway Road these days wants meat that you can bite into, gristle that you can chew on, blood that you can wipe off your lower lip. It wants its beer cold, its curry hot, its lights bright and its music loud. Nothing luke-warm, nothing ambiguous for this crowd.