One of the fun parts of working my way through the Fictions of Jorge Luis Borges is trying to understand where the boundary lies between fact and fiction. In Hakim, the Masked Dyer of Merv, as far as I can tell, the balance tilts further towards fiction than in most of the other stories in his first collection.

One of the fun parts of working my way through the Fictions of Jorge Luis Borges is trying to understand where the boundary lies between fact and fiction. Borges always likes to blur that line by introducing real historical figures and referring to real sources (and a few imagined ones too).

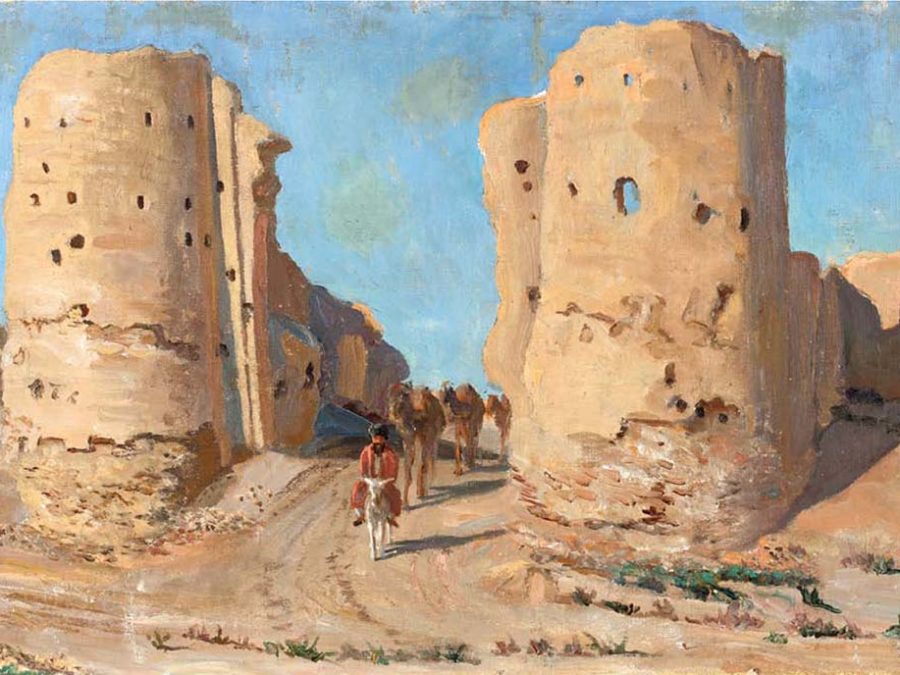

In Hakim, the Masked Dyer of Merv, as far as I can tell, the balance tilts further towards fiction than in most of the other stories in his first collection, A Universal History of Iniquity. We travel much further back in time now, to the 8th-century city of Merv, in modern-day Turkmenistan, to tell the story of Hakim, a man who bears a passing resemblance to the real historical figure of Al-Muqanna, a prophet who always wore a veil and who led an uprising against the ruling Abbasid caliphate.

But beyond the bare bones of the story, there are many elements which Borges seems to have invented, and some of them represent the early appearance of themes that would later become important elements of his fiction.

Mirrors, Maths & Infinity

The philosophy of the veiled prophet Hakim (aka the masked dyer of Merv) is based on a concept that will reappear in later stories: a world based on mathematics. He believes that the origin of all creation is an indescribable deity whose image cast nine shadows. These shadows then ruled over a first heaven, and a second heaven then came into being a symmetrical duplicate of the first, and a third as a duplicate of the second, and so on to the number of 999. That’s where we come in:

The lord of the nethermost heaven—the shadow of shadows of yet other shadows—is He who reigns over us, and His fraction of divinity tends to zero.

With all of this multiplication and duplication, we could easily end up with infinite worlds, each getting further and further away from the original creation. And, Borges (or Hakim) implies, we lose something in the process of copying each time, so that each new duplicate is an inferior version. So the process must stop with us:

The earth we inhabit is an error, an incompetent parody. Mirrors and paternity are abominable because they multiply and affirm it.

So, Hakim (or Borges) claims, the appropriate response to this incompetent parody is to refuse to perpetuate it through further duplication. No mirrors, no kids. It’s an interesting inversion of the popular religious commandment against making images of God’s creation because it’s so perfect—Hakim makes the same injunction, but on the grounds of its imperfection. As for procreation, although there have been several heretical sects who banned it, for obvious reasons they didn’t last long.

The Rise and Fall

Like the other protagonists in A Universal History of Iniquity, Hakim the masked dyer of Merv doesn’t last long either. He enjoys his time of glory, leading his army to victory after victory. His followers’ faith derives from the veil he always wears, which they think is because his face, having been blessed with truth by God himself, cannot be viewed by mortal men without making them blind.

The somewhat shabbier truth emerges, however, when first nails and then a whole finger drops off his right hand. A couple of bold captains finally dare to snatch away the veil, revealing not the beauty of God but a face riddled with leprosy. He attempts to explain it away, but is cut off by a typically laconic Borges ending:

No one was listening; he was riddled with spears.

There are 6 comments

Oh my! That’s quite a story with quite an ending.

Yes, I love those sudden endings of his!

It’s interesting that you find one of the most interesting aspects of reading these stories being to tease out the line between fiction/non-fiction (perhaps I would better say fact and invention?) in his writing. I wonder, though, if he would be pleased that that’s what’s so intriguing to you. (Not that that matters!) I did read a book with edited selections about his thoughts on writing and crafting over the summer last year, when I couldn’t get hold of a copy of this one, but I don’t think anything was said there which really answers my question. It’s just something I’m thinking about now, whether he mightn’t have wanted you to believe it was all true and real or whether he might have hoped you’d think it was all too magical to have actually happened.

You’re probably right! I wouldn’t be surprised if he considered the difference to be unimportant. I think it’s interesting to me in these early stories because he’s basically reciting existing factual accounts—the craft in these ones lies in the extent to which he fictionalises or arranges the facts for his purposes. In the later stories, there’s a lot more invention, and the tactic is more to use the illusion of fact to make the fiction seem more real. So I’ll probably be talking about it less as I move on to the next collections!

Do you think that he could also be commenting on the orientalist poems in Lalla Rookh about a veiled prophet by Thomas Moore as well?

Very interesting! I haven’t read those poems, but they sound as if they are on the same subject, so it’s a very plausible theory. Thanks for visiting and for raising this possibility.