My thoughts on this Japanese classic, which explores themes of guilt, responsibility, individualism, and more.

What makes a book into a classic? The quality of the story and the prose style is a huge part of it, of course, but I think it’s also about somehow rising above the particulars of the story and grappling with themes that are relevant to all ages.

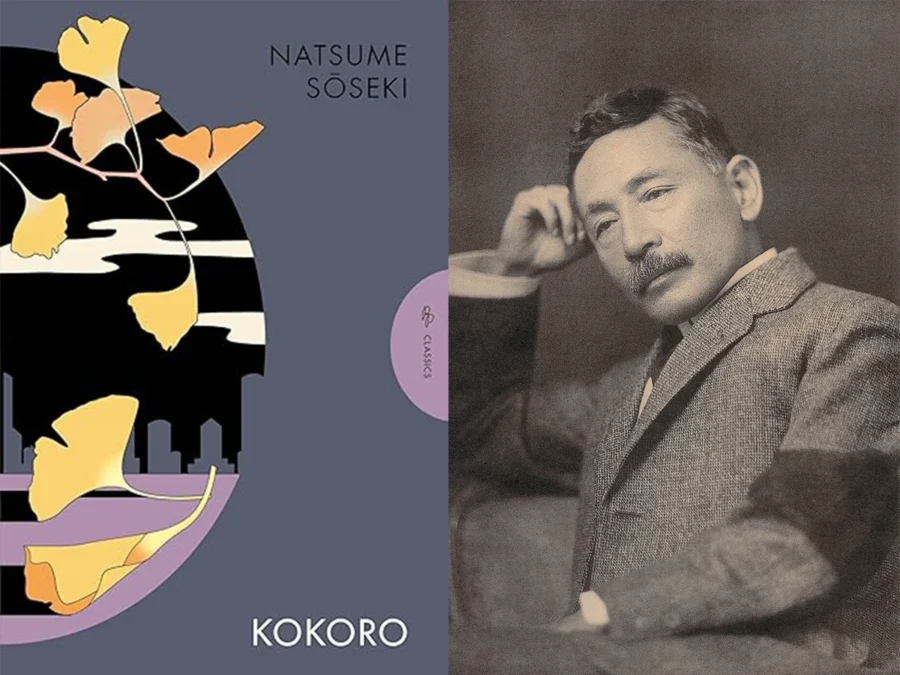

Kokoro by Natsume Soseki is one of the best-selling novels of all time in Japan, and I can see why. It’s a story about a young man’s complicated relationship with his older mentor, but it’s also a beautiful evocation of the end of the Meiji era, and beyond that it’s a meditation on timeless themes like guilt, honour, and atonement.

The book comes in three parts. In Part 1, the young narrator meets an older man whom he comes to call “Sensei”. Although the word is generally translated as “teacher”, the Sensei character in this book is not a teacher in the way we normally understand the word: he holds no academic position, indeed no position of any kind. He has retreated from the world and lives a ghostlike existence, shunning contact with most people except his wife. The narrator is at first offended by his aloofness, only coming to understand it much later:

“I pity him now, for I realize that he was in fact sending a warning, to someone who was attempting to grow close to him, signaling that he was unworthy of such intimacy. For all his unresponsiveness to others’ affection, I now see, it was not them he despised but himself.”

Part 1 proceeds quite slowly, with the narrator gradually getting to know Sensei and becoming both intrigued and frustrated by his older friend and mentor. The only clue he gets to Sensei’s odd behaviour is the fact that he makes monthly visits to the grave of an old friend.

In Part 2 of Kokoro, the narrator graduates from university and leaves Sensei behind in Tokyo to return to his country home, where his father is slowly dying. At the same time, the emperor is also dying, signalling the end of the Meiji era. When the emperor finally dies, a prominent general commits suicide to join his master in death. With his father close to death, the narrator receives a letter from Sensei in which he finally explains the secrets from his past that have cast such a shadow over his life.

Part 3 consists of this very long letter, essentially a memoir of Sensei’s life, focusing in particular on the way he was betrayed by his uncle and then came to betray his own friend, K. The guilt over that betrayal is what has made him retreat from the world—but more than that, it’s a kind of existential crisis brought on by the realisation that even good people will do the most evil things in particular circumstances. His uncle betrayed him for money, and he betrayed his friend for love. After that, he cannot function in the world:

“True enough, my uncle’s betrayal had made me fiercely determined never to be beholden to anyone again—but back then my distrust of others had only reinforced my sense of self. The world might be rotten, I felt, but I at least am a man of integrity. But this faith in myself had been shattered on account of K. I suddenly understood that I was no different from my uncle, and the knowledge made me reel. What could I do? Others were already repulsive to me, and now I was repulsive even to myself.”

And this is where Kokoro takes on broader resonance. The Meiji era brought a conflict between traditional Japanese values and the new Western individualism being brought in from outside. The old moral code emphasised honour and responsibility for one’s actions, exemplified by the general who committed suicide, partly out of loyalty to the emperor and partly to atone for his failures on the battlefield years earlier.

Sensei is caught between these two worlds: he is unable to live up to the stringent moral code of traditional Japan, but he is also unable to free himself from it and fully embrace individualism. So he lives his life in regret and remorse for his own moral failings, as well as bitterness over the failings of others, until he is finally able to expiate it all through the powerful letter he writes to his young friend, in which he lays bare the secrets he has been carrying for decades and warns the narrator to avoid his mistakes.

The structure of Kokoro is interesting: the first two parts are quite slow-moving, while Part 3, narrated by Sensei himself, packs the real emotional punch. Yet the power of Part 3 partly depends on the earlier sections—it’s about contrasting the old, dying traditional values with the newer ways of the younger generation. So although I’d be tempted to suggest that Soseki could have written Part 3 as a standalone novel, in the end I think that all three parts play an important role.

So although I found Kokoro somewhat uneven, I can certainly see why it became a classic of Japanese literature. I’d recommend reading it—and if you do, just hang in there through the first two parts. Part 3 is worth it!

I wrote this post for Japanese Literature Challenge 19, hosted by Dolce Bellezza. Check out her site for more discussion of books from Japan throughout January and February.

There are 10 comments

Neat! I enjoyed Kokoro very much.

And when answering a questionnaire for The Classics Club, I just realized Soseki is the Japanese classic author I have most read – 10 books,

Modern Japanese is Haruki Murakami (21 books)

Wow, that’s a lot – which would you recommend I read next? So far I’ve only read Kokoro.

I take your advice, knowing that part 3 is especially rewarding helps keep perspective.

Yes, it’s worth hanging in there for part 3!

Hunh, interesting. I just read an introductory essay to Walter Scott’s The Heart of Midlothian and it has a similar theme (social/political change and how one can be caught “in between”: different country, different era, but that one element seems consistent and likely appears in many other classics as well.

Yes, I think it’s one of those perennial themes that cuts across different cultures. Reminds me of a lot of postcolonial literature too.

I really like the sound of this one, and the slow pace of the first two parts probably wouldn’t worry me (based on the types of books I enjoy reading). I read Soseki’s novel The Gate some years ago and loved it, so maybe it’s time for me to return to him this year.

Yes, I think you’d enjoy this. Thanks for the recommendation – will look up The Gate now

Andrew, your reviews are rich in content and exquisite in delivery. What a pleasure to read what you have to say about books!

I am struck, immediately, by this quote from Part 1: “For all his unresponsiveness to others’ affection, I now see, it was not them he despised but himself.”

Wow. That alone gives me such pause, as I think about relationships I have known, and even ways I have felt myself at times.

I have Kokoro on my shelf, of course I do, unread. Since I find myself with a broken foot, on top of everything else that has happened lately, I surely must read it this time through the Japanese Literature Challenge 19. Thank you for your participation.

Thanks so much, Meredith! Yes, that quote is beautiful and poignant, isn’t it? It takes on extra resonance as we read more in Part 3 about Sensei’s character and his guilt over his past actions. I can certainly relate to it as well – it’s common to associate aloofness with a sense of superiority, but I think it’s often attributable to the very opposite.

Hope you get to Kokoro for this JLC and that you like it as much as I did! Thanks again for hosting this wonderful event. I’ve had a busy start to the year and haven’t had much time to read other entries, but I’ll try to catch up now.