A harrowing true account of a small child surviving the Cambodian genocide.

One of the most harrowing parts of my trip to Asia and the Pacific earlier this year was visiting Cambodia and learning about the horrific crimes of the Khmer Rouge in the Cambodian genocide, in which the government killed around 2 million of its own people, around a quarter of the country’s population, in less than four years.

In the capital, Phnom Penh, Genie and I visited the notorious S-21 prison camp, a former school where the Khmer Rouge imprisoned and tortured thousands of people before taking them to be murdered in the “Killing Fields” on the edge of the city. On the way out, we met Norng Chan Phal, who had been imprisoned at S-21 as a small child and was one of only a handful of survivors. Genie took the photo shown above and we bought a copy of his book, which tells his story.

Although it’s Norng Chan Phal’s story, the book was written by Kok-Thay Eng, a Cambodian academic who put it together based on interviews and archival research. So it tells the personal story of a child caught up in the middle of genocide, but it also provides some useful context about what was happening in Cambodia at the time.

Even with the context, though, the suffering is completely senseless, and that’s one of the hardest things to understand about the Cambodian genocide. The story starts before the Khmer Rouge came to power, with Norng Chan Phal living a simple but happy rural existence with his family, who were relatively successful thanks to his father’s carpentry business and the income from a herd of cows and buffaloes on their family farm.

After the Khmer Rouge took power, all private property was collectivised. The family lost their livestock and possessions and were sent to work on a collective farm far away in another part of the country. Conditions were tough, but they survived and adapted to the new reality of working for the collective.

But then people began disappearing, for no reason anyone could discern. The Khmer Rouge would just come and take them to Phnom Penh, and usually they’d never be seen again. There was no reason given—the disappearances seemed random. Then, one day, they came for his father, and a little later, they came for his mother, along with Norng Chan Phal and his little brother.

This is how the genocide worked, according to what we learned at S-21. The Khmer Rouge was constantly on the lookout for enemies and was particularly suspicious of people like Norng Chan Phal’s family, who although not rich, had previously enjoyed some relative wealth and possessions. So they rounded up people, took them to a place like S-21, and tortured them until they confessed to being enemies of the revolution and provided names, any names. Then they rounded up those people, and anyone associated either with the original detainees or the new ones. Once people had confessed and provided more names, they were killed. If they didn’t confess, they often died under torture or from starvation or sickness in the camp. It was just a vast, senseless machine for destroying human life.

When they were first taken from the collective, Norng Chan Phal was excited. He was a little boy and didn’t understand what was happening. He thought he was being taken to see his father in the city and would get his favourite prewar treat of a cone of shaved ice with sweetened coconut milk. But he never saw his father again. He saw his mother being beaten and tortured, and then he and his brother were separated from her and sent to the kitchen with some other very small children. He glimpsed her once looking down at him from a barred window, gesturing at him to stop his brother from crying so that the guards wouldn’t punish them. When he looked up again from calming his brother, she was gone. He never saw her again either.

The Khmer Rouge regime was toppled by invading Vietnamese forces in 1979, and the guards cleared all the prisoners out of S-21 as word spread that the Vietnamese were approaching. Norng Chan Phal still believed his parents to be alive at that time and worried that they would never find him if he was evacuated, so he hid in a pile of dirty clothes and told the other children to do the same. It saved his life: most of those who were evacuated did not survive.

For long days, the children lived in the abandoned prison camp, too scared to leave their hiding place. As the oldest, Norng Chan Phal eventually went out to see what was happening, but found only the bodies of people tied to beds with their throats slit. Finally, the Vietnamese forces found them, and they were taken to an orphanage.

Years later, Norng Chan Phal reunited with those of his siblings who had survived and discovered that his parents had not. The last part of the book details his adult life, in which he married and had children and worked in construction.

“Phal felt proud and said, ‘My brother, our co-workers, and I were satisfied with our work since Cambodia was torn by wars for many decades; bridges, dams, buildings, irrigation system, and infrastructure were severely destructed. On behalf of a Cambodian citizen, I had to share my responsibility to reconstruct what was destroyed.”

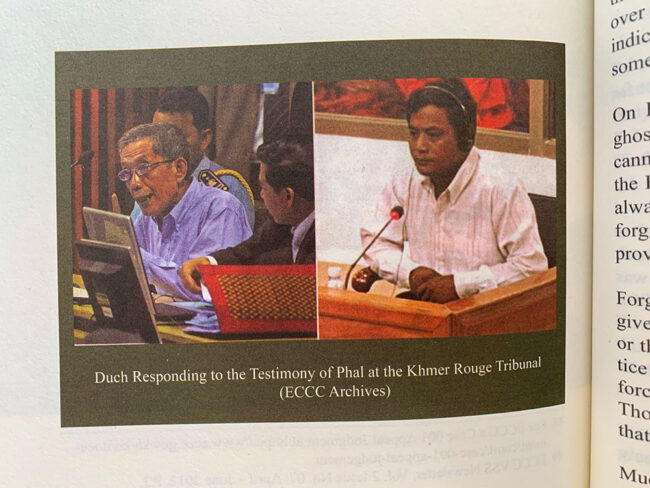

He also testified as a witness at the tribunals at which former Khmer Rouge leaders were tried and sentenced, including the former head of S-21.

The book ends on a note of reconciliation, with Phal now a “happy family man bearing no grudge against the Khmer Rouge.” The author gives other examples of the incredibly difficult task of reconciliation taking place around Cambodia.

Reading this book was like visiting S-21 and the Killing Fields: it’s very hard and harrowing, but I learned a lot from it and am glad I did it. The pain of reading and learning is infinitesimal in comparison to what Norng Chan Phal and millions like him suffered under the Khmer Rouge. We need to read stories like this if we are ever to evolve beyond saying “Never this specific type of atrocity again” and get to the stage where we refuse to accept or justify any atrocities against any people.