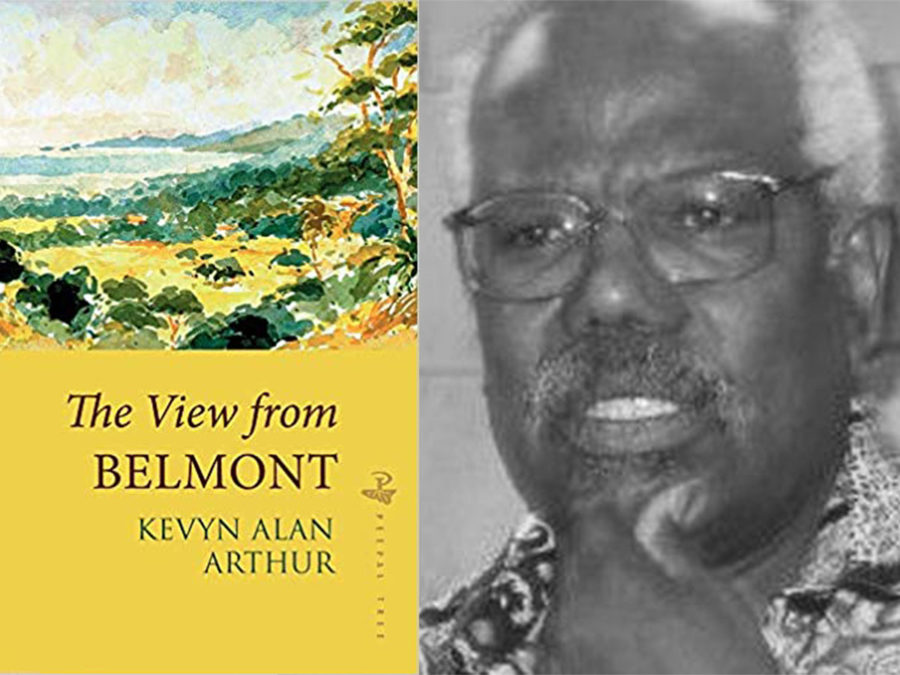

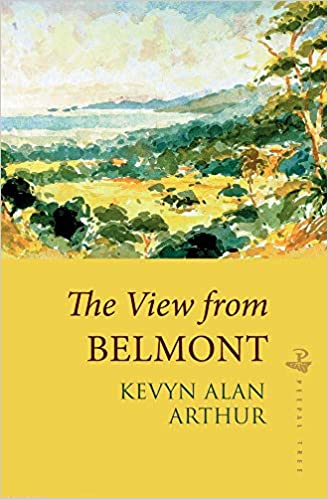

The View From Belmont raises interesting questions of race and gender amid the barbarousness of a slave-owning society. The dual narrative was a promising technique, but it didn’t feel fully realised to me. I’d have liked more of 1990s Trinidad to counter-balance the historical narrative.

The View From Belmont is another piece of Caribbean literature from my bookshop purchases in Barbados, and funnily enough, my review will be very similar to my review of Cambridge by Caryl Phillips, also from that trip. It’s an interesting dual narrative, but it felt unbalanced to me.

In The View From Belmont, just as in Cambridge, we get the perspective of a young white Englishwoman on a slave plantation in the Caribbean (this time Trinidad). Again, there’s a dual narrative, although this time it’s composed of the letters of the Englishwoman Clara and the responses of a group of Trinidadians who find the letters in the early 1990s.

And again, it’s unbalanced. When I read the setup, I expected much more back and forth between the two narratives. But as with Cambridge, we end up spending the vast majority of our time with the white woman. The modern-day responses are usually just a paragraph or a page, following 10 or 20 pages of Clara’s letters.

There’s also no significant interaction between the past and present narratives. Reading the letters is just an act of curiosity, and it has no real impact on their lives. We also don’t get much sense of their lives or characters beyond the brief introduction.

Still, the idea of a modern response to colonial-era letters is interesting, and it could have delivered more, but there’s only space for limited and quite superficial reactions, mostly revolving around arguments over who likes or doesn’t like Clara and speculation over why the letters remained in Trinidad instead of being sent to England as she intended. It felt like a missed opportunity.

Clara, at least, is a more interesting and sympathetic character than Emily Cartwright in Cambridge. She comes to Trinidad with her husband but is promptly widowed, and her attempt to take over the running of the cocoa estate amid misogynistic scorn from her neighbours is quite compelling. She’s also more of a rebel than Emily, more independent and more compassionate.

Nevertheless, she still supports the institution of slavery, so Clara is definitely a conflicted character and not someone you can exactly “root for”. Then there’s the issue of her relationship with her slave, Kano. Can you actually have a relationship with a person who is legally your property? Can it ever be truly consensual? It feels horribly exploitative and coercive, especially because Kano initially tries to refuse her, and also because Clara doesn’t seem to really know or understand him at all, or indeed to have any real interest in doing so. She wants sex (or, as she puts it, to be “tupp’d by a black ram”, but she doesn’t even let him kiss her:

“I still find the thought of kissing those very large lips of his, in a romantic manner, to be unappetizing in the extreme!”

The modern-day Trinidadians argue about Clara and Kano, with some taking Clara’s side and others not:

“Thelma say, ‘But look at this worthless white bitch, eh?’ and Barbara say, ‘You ain’t shittin’.’ But Ruby, as usual, went to Mrs. Bayley defence, arguing how she think the woman being sensible and taking charge of her life, and all she really wanted was companionship, that she could sympathise with her.”

The View From Belmont raises interesting questions of race and gender amid the barbarousness of a slave-owning society. The dual narrative was a promising technique, but it didn’t feel fully realised to me. I’d have liked more of 1990s Trinidad to counter-balance the historical narrative.

There are 6 comments

Interesting that so much of the narrative is spent on the white woman. I wonder why that is? Do you think if it was more from the Black perspective and more blatantly critical that it would have had difficulty finding a publisher? And if so, that says a lot about white supremacy and colonialism and how its consequences continue to be an issue.

Another good question! I don’t know why he did it this way, but you may well be right. Your comment reminded me of a visit to an old Barbadian slave plantation that was full of exhibitions on the plantation owners’ lives and the details of their farm machinery, but had very little mention of what life was like for the enslaved Africans who did all the work. When Genie asked why Black people were not represented, the staff member said it was a “sensitive subject” ????

There are a couple of fascinating chapters in Clint Smith’s How the Word is Passed about decisions made around whose perspectives are represented and all those overlooked “sensitive subjects” at tourist sites (and prisons, often constructed on old plantation sites, count as tourist destinations, cuz there’s merch for visitors apparently!).

Oh, thanks for the recommendation! That sounds like a wonderful book. I’d read about the gift shop at Angola, perhaps in an article based on this book now that I think about it. Time to read this one!

Hunh, that’s curious! Especially given that you’ve read another book recently which seems to exhibit the same pattern.

In this case, because there’s an explicit dual narrative, it seems to invite the question of fairness and representation even more directly.

Is it possible that the author was trying to make this point, in fact? That the dominant narrative in colonialism drowns out all the other voices. Another form of erasure?

There have been studies done recently which show that a diverse staff leads to benefits for workplaces and employers (for instance, in terms of different perspectives for more dynamic problem-solving) because there are more voices in conversations. Maybe Arthur was deliberately illustrating what it’s like when a single character’s perspective sucks all the air out of the room and leaves so much unsaid and unacknowledged on the other side of the conversation?

Good point – that could be the purpose in both cases. If so, however, I didn’t find it very successful. It felt more like reinforcing the dominance of the white narrative than illustrating or challenging it. But it’s interesting to think about why these authors chose to write this way, so thanks to you and Stefanie for contributing some good ideas!