As the Empire was falling apart, Britain had a problem: how to keep control of all its former colonies and their resources as they became independent.

Acting in good faith was, of course, out of the question. Many of the leaders pushing for independence were talking of using their resources for the benefit of their own people, which went against everything the Empire had always stood for.

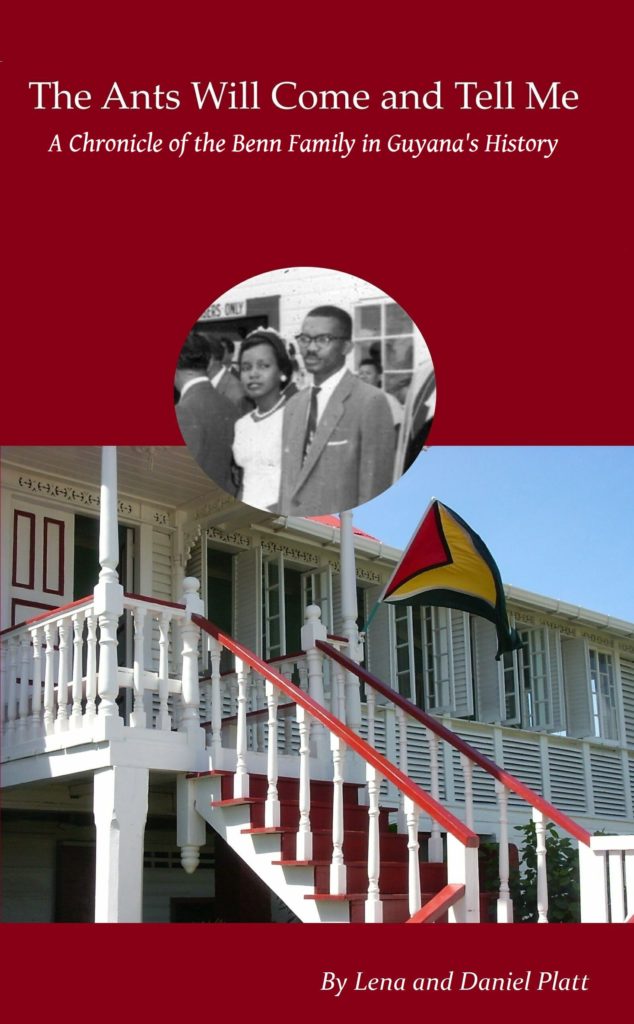

The solution they came up with was to hand-pick pliable leaders and discredit or destroy those who would oppose imperial interests, using the grimly familiar “divide and rule” strategy. In the new book The Ants Will Come and Tell Me, Lena and Daniel Platt tell the story of how this took place in Guyana.

The book is a history of both a family and a nation. Lena Platt is the daughter of Brindley Benn, one of the leaders of the Guyanese independence movement, and she tells the story of Brindley and his wife Patricia both as a political story and a family history. We see what it meant to the family when Brindley was arrested in 1953 as the British suspended Guyana’s constitution and imprisoned its opponents to pave the way for Forbes Burnham, their chosen candidate and a man who brought political repression and economic chaos to Guyana for decades. We see how that chaos affected the children, some of whom migrated across the globe in search of opportunity, while others stayed to try to improve things.

Race is an important dimension of the book. Guyana today is deeply divided along racial lines, with the predominantly urban descendants of enslaved Africans pitted against the predominantly rural descendants of indentured Indians. What this book taught me was that both groups initially worked together for Guyanese independence, only splitting in the mid-1950s when Forbes Burnham left the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) led by Cheddi Jagan and formed his own People’s National Congress (PNC).

Brindley Benn was notable for being one of the few Afro-Guyanese politicians to remain in the Indian-led PPP instead of joining Burnham’s predominantly Afro-Guyanese party. This led to trouble at various times, with the family receiving threats and with Benn’s political career suffering from his refusal to play along.

“Brindley Benn and his family were targeted with a special venom, because Brindley was an Afro-Guianese leader who refused to play into the race war scenario which had been carefully crafted by the British.”

The book cites newly declassified CIA memoranda to show that Burnham, on the other hand, was supported both by the UK and the USA, who saw him as less “radical” than the likes of Jagan and Benn. Here’s a quote from one CIA memorandum, which talks of the CIA’s “covert action” in Guyana and refers to a redacted “operation”:

“The CIA contacted Burnham subsequently, and in return for promise of financial assistance to the PNC, he gave assurances respecting his political program.”

When Burnham finally took power with US and UK help in 1964, he didn’t relinquish it until his death in 1985. His rule followed the same trajectory as so many dictators in money-poor, resource-rich nations around the world: as long as he kept the resources flowing, he received staunch Western support despite his undemocratic rule, but when he began to nationalise important industries like bauxite and sugar, he became a pariah.

One of the strengths of this book is the authors’ inside knowledge of the Benn family, the Jagans, and other players in the Guyanese political world. We get a real sense of what life was like for them as individuals, not just politicians or historical figures. And it also sheds light on the broader social history of the country.

But the closeness of the authors to their subject matter also means that this is not a dispassionate academic account. This is Guyanese history from the point of view of the Benn family. Important facts, like Burnham’s CIA backing, are well sourced and accounted for, so you can trust the facts presented in the book, but don’t expect to see criticism of Benn or the family members.

What you will see is a compelling account of an important period in Guyanese history. You’ll see the detail of how external powers can interfere in a country’s destiny, from overt measures like the British suspension of the constitution to covert support for divisive figures and subtle changes to the electoral system that shifted the balance of power. The book quotes Arthur Schlesinger Jr reflecting decades later on his role in advising President Kennedy on how to get Jagan out of power:

“I felt badly about my role 30 years ago… what really happened was the CIA got involved, got the bit between its teeth and covert action people thought it was a chance to show their stuff… I think a great injustice was done to Cheddi Jagan.”

Brindley Benn was politically marginalised under the long Burnham regime, but The Ants Will Come and Tell Me continues his story right up to his death in 2009, and the book also brings us right up to date with Guyanese history, including further US interference in the 2015 election and then an account of the crazy saga of the long-delayed 2020 election, which led one official observer to say:

“I have never seen such a barefaced, ugly and deliberate attempt to rig an election. Yes, I have seen attempts and I am aware of attempts where elections were rigged, but not in this kind of manner; not in this ugly, barefaced and obvious manner. It was utterly disgusting.”

I’d viewed the election controversy from the outside with confusion, not really understanding all the different parties and what was at stake, so I found the detailed account in this book a useful explainer.

Overall, I’d recommend The Ants Will Come and Tell Me to anyone with an interest in Guyanese history, or to general readers who want to understand why, more than half a century after the main wave of decolonisation, so many of the newly independent nations have struggled to escape from their former colonisers.

The book’s title refers to Benn’s hopes for a better, fairer world, which he didn’t expect to see in his lifetime but which he hoped the ants would come to his grave and tell him about. Right now, I hope the ants are maintaining a discreet silence, but the thing about beliefs like Benn’s is that they’re so rooted in basic, commonly shared ideas of fairness and justice that their time must come eventually.

With climate change making the policy of aggressive resource extraction seem even more insane than it did before, I can only hope that events like those detailed in the book, in which the freedom and rights of half a million people were sacrificed for some rich countries’ need for bauxite, will be consigned to the dustbin of history. And if I’m not around to see it, please arrange for some ants to come and tell me too.

There are 4 comments

Sounds like a great book. You’d think the US and UK would learn that their continued interference in other countries in supporting often despotic leaders because they think thy will be more pliable is a failed strategy that only comes back to bite everyone in the backside. But no, they keep at it all to for the sake of corporations being able to make more money. Grrr.

Yeah, you’d think 😉 The thing is, I think a lot of people in the US and UK do understand this, but we don’t have the power to change it. And the people who do have the power don’t want to change it. I used to think our leaders were trying to act in the national interest and were incompetent. Now I think they’re acting according to narrow class interests and are very successful.

Perhaps you can arrange for communications yourself by skillfully deploying trails of sugar or honey!

This sounds like an informative read. The political machinations remind me of how lost I felt through much of Marlon James’ Brief History of Seven Killings (which also described a lot of American influence in inappropriate places and a lot of political party names that seemed like they should be more pro-people).

Haha, yes! Why didn’t I think of that?

The political machinations are hard to convey in a review without it seeming like alphabet soup, but it felt quite clear in the book, even though the subject matter was mostly new to me. Ah yes, that’s another book I meant to read but never got around to. That’s a long list!