I love the writing of Jorge Luis Borges. Back in the early days of this blog, I was so deeply affected by reading his collection of ‘fictions’ that I broke my optimistic vow of reviewing every book I read. It seemed impossible to review a book so vast and varied—it would be like trying to catalogue the contents of one of the infinite libraries of Borges’s stories.

So, instead, I set myself an even more impossible task: to review each story individually. All 101 of them.

My failure was predictable—the only disappointment was that I didn’t even get past the first review: a look at the bizarre life and abrupt death of the cruel redeemer Lazarus Morell. Then, life intervened: two books published, a move across the Atlantic to Barbados, then back across to Crete, and then five years of living everywhere and nowhere.

The Borges Collected Fictions lay waiting all this time in a cardboard box in my parents’ loft, finally emerging again last year for me to reread and be amazed by all over again.

And so, more than 11 years after my brief encounter with Lazarus Morell in part 1, I have decided to resurrect this impossible project and embark on part 2 of my Borges Marathon: the story of Tom Castro, the improbable impostor.

Note: all of these reviews will contain spoilers. I don’t know how to review stories as short as these without mentioning important plot points.

The Improbable Impostor Tom Castro

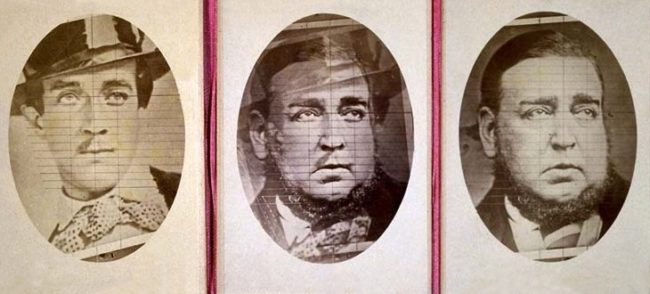

In one sense, The Improbable Impostor Tom Castro is a simple story of an impostor claiming the identity of a long-lost aristocrat, playing on the desperation of the missing man’s mother to deceive her and claim the Tichborne family fortune.

But this is Borges, so nothing is simple. The impostor, Tom Castro, is no evil genius: he’s a simple, bumbling Englishman who “could (and should) have starved to death” as a young man in South America but somehow made it to Australia, where he meets the concoctor of the plot, a black man called Ebenezer Bogle who is as astute as Castro is slow-witted. Bogle’s only apparent weakness is a prescient terror of crossing the street.

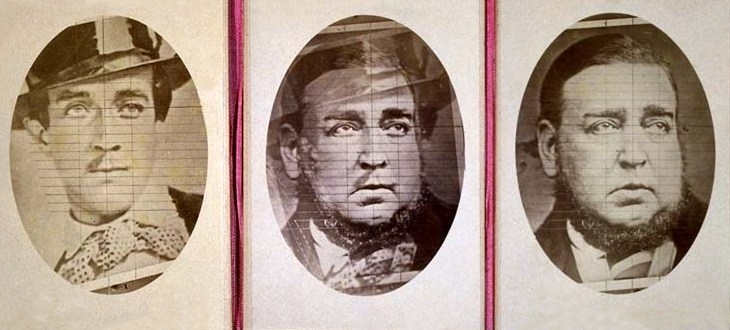

Bogle’s genius consists of realising that if he wants to claim the Tichborne fortune, it would be useless to put forward an impostor who resembles the missing man.

“Bogle knew that a perfect facsimile of the beloved Roger Charles Tichborne was impossible to find; he knew as well that any similarities he might achieve could only underscore certain inevitable differences.”

So instead he puts forward Tom Castro, a man who bears no physical resemblance to Roger at all, a man who is virtually illiterate when Roger was articulate and well-read, who speaks no French when Roger was fluent in it.

“He sensed that the vast ineptitude of his pretense would be a convincing proof that this was no fraud, for no fraud would ever have so flagrantly flaunted features that might so easily have convinced.”

Why Does the Story Work?

Borges plays with fiction and nonfiction all the time in his stories. He frequently uses elements of fact, but changes details at his own whim, gleefully blurring the usually sharp lines between fiction and nonfiction.

The Improbable Impostor Tom Castro is based on a real story, the famous Tichborne case from Victorian England. But the character of Ebenezer Bogle seems to be completely invented, as far as I can tell: the only mention of a similar character in real life is Andrew Bogle, a former slave who was a witness in the case but played no central role. A bogle is also a mischievous sprite in Scottish folklore, which may have added to the appeal of the name.

As with the story of Lazarus Morell, The Improbable Impostor Tom Castro disobeys the usual rules of storytelling. Just as it is building to a climax, the story deflates. Key events like the deaths of main characters and the unmasking of Tom Castro’s elaborate fraud happen off-stage and are remarked upon in passing. We are shown only a few brief scenes, like the meeting of Bogle and Castro in Australia and the joyous ‘reunion’ of Lady Tichborne with the man she believes to be her son. The rest of the story reads more like a biography. It shouldn’t work, but it does.

I think the story works because it eschews the artifice of storytelling. The detached style of a nonfiction book, the lack of symmetry or a plot arc, the inconvenient interventions of Fate: all of these make the story of Tom Castro seem more real, more true to life.

Borges is like Ebenezer Bogle, spinning us the most unlikely of tales and using a counterintuitive strategy to convince us. Remember that line about the ‘vast ineptitude of his pretense’? Borges, like Bogle, flagrantly flaunts the features that might so easily have convinced. He could so easily have used the techniques of storytelling to build believable characters, to show us scenes and bombard us with details that appeal to our senses and help us to see the story as real.

The fact that he does none of these things echoes the way that Ebenezer Bogle produces an impostor who doesn’t even try to look or sound like Roger Tichborne. By not even trying to sound convincing, he convinces us. Also in his favour is the fact that readers, like grieving mothers, desperately want to believe.

Read more posts in my “Borges Marathon” here.

There are 8 comments

Well, better late than never for the story reviews! And perhaps with the passage of time and experience and rereading them, it will all be that much richer for it. Really liked how you talk about why the story works.

Thanks, Stefanie! Oh, I see your link hass changed. I look forward to checking out your new blog. Exciting 🙂

Hi Andrew, thank you for your great reviews of Borges! They are truly helpful gaining new perspectives as a reader who is new to Borges, and motivate me to read his stories more carefully. I now embark on my (lifelong?) journey: reading a Borges story, and then reading your review as a conversation with a friend, afterwards. I am reading them in Dutch (so please forgive me for not sharing my own interpretations – since this would only lead to crooked, non-native English expressing – due to a lack of vocabulary – to superficial thoughts). But know your reviews are much appreciated!

Petra

Hi Petra, Thanks so much for leaving this comment! I have been writing these Borges reviews mostly for myself and was wondering if anyone else found them interesting or worthwhile. So your encouragement means a lot to me. I haven’t made progress with my Borges Marathon for a few months now, so I think it’s time to return to it.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on any of the stories, and please don’t feel constrained by language. Judging by this comment, I’d say your English is excellent! In any case, it’s good to know that I have a conversation going on with a friend somewhere in the world.

The idea that he is not trying to sound convincing being one of the elements that makes him seem all-the-more convincing intrigues me. It’s like that old adage about how the most effort of all can go into a book that appears to be effortlessly constructed. I’ll enjoy following along with your project. And even though I no longer have my copy of this collection, I might borrow one from the library at some point and read a few alongside.

I’d love it if you could read along for a few! It would be great to get your perspective on the stories, and it would also give me some motivation to complete this project some time in this century 🙂

Nice presentation! I discovered Borges in my late teens, loved his writing then. Definitely time to revisit, thanks for reminding me

Thanks Emma! I found so much there on a second reading recently after a long gap, so I hope you do get to revisit him.