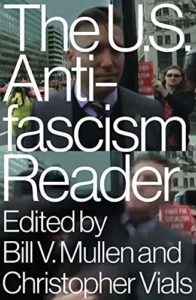

Reading The US Antifascism Reader lately gave some useful context on this much-maligned but essential movement. It’s a collection of essays and speeches by historical figures from W.E.B. Du Bois to Franklin Roosevelt, Aimé Césaire to Barbara Ehrenreich, in which we see different approaches to combating the dangers of fascism.

For most of my life, opposing fascism was something that most of us could agree was a good idea. Then anti-fascism was shortened to “antifa” and characterised by President Donald Trump as a shadowy, violent threat to the nation’s security. I spoke to a couple of people in the U.S. who complained about antifa radicals infiltrating Black Lives Matter protests, without even realising what antifa stood for.

Reading The US Antifascism Reader lately gave some useful context on this much-maligned but essential movement. It’s a collection of essays and speeches by historical figures from W.E.B. Du Bois to Franklin Roosevelt, Aimé Césaire to Barbara Ehrenreich, in which we see different approaches to combating the dangers of fascism.

Street combat was always one tactic used by the movement, but it was far from central. Despite the media mischaracterisations (e.g. this viciously inaccurate Fox News hit piece that makes antifa sound more like Al-Qaeda), that’s still true today. Throughout the movement’s history, dialogue and conversation have been much more important than violence. That’s not surprising, since the whole point of anti-fascism is to defend democracy and freedom against the existential threat of fascism. Violence is a last resort, to be used sparingly—otherwise, the movement would be utterly self-defeating and wouldn’t have lasted so long.

To define anti-fascism, of course, you have to be clear about what fascism is, since that’s a term that often gets lobbed around as a general term of abuse. The editors of this book, Bill V. Mullen and Christopher Vials, define fascism as:

“a particular strand of right-wing politics, separate from classical conservatism or even other strands of right-wing authoritarianism (e.g. Pinochet’s Chile, the Somozas’ Nicaragua), in that it is not driven primarily by traditional elites wishing to preserve their economic interests. Rather, it is a largely middle-class movement animated by a highly symbolic, populist, and mythic drive for national renewal, grounded in militarism or male violence, anti-Marxism, racism, and authoritarianism. In addition, it actively mobilizes the population against national minorities and/or the political left.”

By this definition, traditional elites are not the drivers of fascism but its enablers. They often support fascist movements in their early days because of their own fears of left-wing movements and working-class enfranchisement, but in the end they get swept aside themselves because fascism is a movement that comes from outside the traditional ruling class. This fits in quite well with what I know of the rise of Hitler in Germany and Franco in Spain, among others.

Anyone who’s paid attention to Donald Trump’s speeches will notice that he ticks quite a few of the boxes in the above definition of fascism. MAGA was a drive for national renewal, and his speeches were peppered with the language of male violence, racism, authoritarian rhetoric, violent antipathy to the left, and attacks on minorities.

What stopped Trump from being a true fascist was probably his short attention span. True fascists build well-organised movements, with disciplined, violent cadres to take control of the levers of power. As infuriating as Trump’s tweets were, it’s probably lucky that he wasted so much time on Twitter instead of building a movement that could have taken control of the Capitol instead of just invading it for a few hours and taking selfies.

So Trump was not a true fascist by this book’s definition, but anti-fascists opposed him anyway. That gets to the heart of the dilemma faced by anti-fascism throughout history: how do you decide who is a fascist, who is dangerous enough to oppose? If you move too soon, you shut down debate with well-meaning conservatives; if you wait too long, it’s too late.

A true fascist, given the chance, will destroy democracy, imprison or kill his opponents, and shut down the possibility for principled opposition. Last year, I read the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci, an Italian Member of Parliament who was arrested by Mussolini, along with many other members of the parliamentary opposition, and spent most of the rest of his short life in jail, where he defiantly resisted the famous wish of his prosecutor: “For twenty years we must stop this brain from functioning.”

Some of the essays in The US Antifascism Reader grapple with this very problem: how to identify fascists and stop them before they have so much power that they destroy the ability to stop them. And how to stop them without undermining the very democracy you’re trying to protect.

Other essays put the focus of anti-fascism less on leaders and more on the population. What makes some people susceptible to fascism? The excerpt from the 1950 book The Authoritarian Personality by Theodor Adorno and a group of Berkeley psychologists covers an interesting attempt to develop a scale to measure “implicit antidemocratic trends”. They postulated that personality traits, many formed in childhood, made some people more prone to accept fascist or anti-democratic propaganda. These traits are:

- Conventionalism

- Submissiveness

- Aggression against those who violate conventional values

- Opposition to subjective/imaginative tendencies

- Superstition

- Preoccupation with identifying people as strong/weak, leaders/followers

- Destructiveness and cynicism

- Outward projection of their own emotional impulses

- Exaggerated concern with other people’s sex lives

I also liked Aimé Césaire’s essay linking fascism with colonialism and arguing that fascism involves European countries applying the violence of colonialism internally against segments of their own populations. Fascism is, for Césaire, a consequence of colonialism:

“What am I driving at? At this idea: that no one colonizes innocently, that no one colonizes with impunity either; that a nation which colonizes, that a civilization which justifies colonization—and therefore force—is already a sick civilization, a civilization that is morally diseased, that irresistibly, progressing from one consequence to another, one repudiation to another, calls for its Hitler, I mean its punishment.”

There’s a lot more in this book, too much to cover in a single post. Unfortunately, the demise of Trump doesn’t mean the end of the threat of fascism in the U.S. And Europe has plenty of its own far-right movements to contend with. As more and more people become rightly disillusioned with the political elites that have treated their lives as something disposable, they will look for alternatives, and the job of people who care about democracy is to ensure that fascism is not the alternative that triumphs. It’s been a long struggle, and The US Antifascism Reader contains useful lessons from people who’ve fought the same fight in the past.

The ebook version of The US Antifascism Reader is currently free to download from the Verso Books website.

This post is my contribution to Reading Independent Publishers Month (#ReadIndies), hosted by Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings and Lizzy’s Literary Life. The idea is to celebrate indie publishers by reading and reviewing their books. It runs for the whole month of February, so there’s plenty of time to join in! Thanks to Vishy for letting me know about it.

Verso calls itself “the largest independent, radical publishing house in the English-speaking world”, and I find it a great source of reading about the sort of politics I’m interested in, i.e. how the world works and what we can do ot make it work better, not just the parliamentary machinations that tend to dominate political news. I’ve reviewed several Verso books here, including Arundhati Roy’s reassessment of Gandhi and an exposé of the inherent violence of national borders.

There are 9 comments

I’m a great fan of Verso, and this sounds like a fascinating and necessary book. Fortunately I think I have a copy somewhere. Thanks for taking part in #ReadIndies!

Me too, Kaggsy! I’m a sucker for their year-end ebook sale 🙂 Thanks for organising the event. Is it an annual thing? If so, I’ll put it in the calendar and try to get more organised to post more next year.

Beautiful review, Andrew! This is a very important book for our times. Verso publishers looks very fascinating! Thanks for sharing your thoughts ?

Verso is terrific. And you’ve done a fine job of tackling a very big subject in a relatively short piece. This sounds like essential reading. And I’m echoing your comment that this spectre has not faded for the U.S. (or, elsewhere, for that matter). The recent election could spark complacence, especially for those of us who are wearied, but there are millions of people who voted in favour of 45’s brand of authoritarian power, and many lawmakers afraid to name it as a threat to democracy. At least reading and thinking makes it a little easier to approach difficult conversations.

Yeah, they’ve got some really interesting stuff! I tend to get carried away buying dirt-cheap ebooks in their year-end sale and then slowly working my way through them for the rest of the year. You’re right, the threat doesn’t end with Trump. I’ve been catching up with the TV version of The Handmaid’s Tale lately, and it’s disturbing how plausible it is. I’m watching it, and my skin is crawling most of the time, and yet I’m thinking yep, there are people right now who would want the world to be like this.

Inoffensive review, Andew.

Thanks Jose. Inoffensive isn’t generally the effect I’m going for, but thanks for the feedback.

Written four years ago. How things have changed since this billet.

We were in denial that the Agent Orange could come back but he’s there, more toxic than ever. *sigh*

And things don’t look so good in Europe either.

Yes, I suppose this was written shortly after the storming of the Capitol, which at the time I naively assumed would mean the end of his political career. I remember times when a minor indiscretion would force someone out of politics for good, but now, it seems, there are no consequences for anything. That’s one of the scariest things about the times we’re in.