The transition from childhood to adulthood can often be tough. It must be even harder when you’re a teenage girl in Syria who feels drawn to radical Islamist ideology but also has forbidden lesbian fantasies about her best friend.

The transition from childhood to adulthood can often be tough. It must be even harder when you’re a teenage girl in Syria who feels drawn to radical Islamist ideology but also has forbidden lesbian fantasies about her best friend.

It gets harder still when you find yourself growing up in the midst of a rebellion by the Muslim Brotherhood, with family members on both sides of the widening divide.

And then, to top it all off, you find yourself being manipulated by a male novelist to undermine your own beliefs, turning your certainties to ashes and exposing the self-defeating nature of the hatreds you have come to praise. He also seems to have a preoccupation with your body and describes it in lascivious detail for the benefit of strangers the world over.

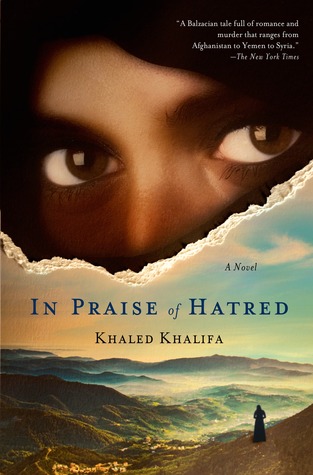

Such is the tough situation faced by the unnamed narrator in the fascinating novel In Praise of Hatred by Syrian writer Khaled Khalifa.

The book is set in 1980s Syria, but the story of ordinary people getting caught up in conflict between the opposing violences of a brutal government and fundamentalist suicide bombers is sadly resonant today. It’s beautifully written, and it sheds light on the interior world of a family making tough choices and sometimes being torn apart in the midst of larger events.

We see the appeal of the various hatreds the unnamed narrator succumbs to. They give her meaning and purpose, provide solidarity with others, and help her to deal with the ultimate hatred: the self-hatred that comes from the conflict between her own feelings and the messages about herself and her body that she receives from the world.

The fact of being unnamed is significant for fairly obvious reasons, and it works quite well within the novel. As she says at one point:

My life was a collection of allegories that belonged to others. How hard it is to spend all your time believing what others want you to believe; they choose a name for you which you then have to love and defend, just as they choose the God you will worship, killing whoever opposes their version of His beauty, the people you call ‘infidels’. Then a hail of bullets is released, which makes death into fact.

This struggle to find your own truth is something most of us go through as we grow up; the difference is that in this girl’s situation, the stakes are so much higher. It’s a powerful and complex portrait of a process that is very specific but also has much wider relevance.

Having said that, I think there’s often a problem when men write about women. It doesn’t necessarily happen, and I’m not saying that men can’t write from a woman’s perspective, but there is a danger of male judgments, preferences and preoccupations being applied to female characters.

I have a personal test I like to apply, and thankfully ebooks make it much easier: just search for the number of times the word “breasts” appears in the novel. If the writer is a woman, it will probably be quite low; for men, it can often be startlingly high.

In this case, the “breast test” results in an eye-watering count of 39. There are breasts with nipples like cherry stones, breasts that smoulder or bounce provocatively, breasts that hang like ripe apples or like tagines of polished marble. And for older or uglier characters, there are unappetising breasts, breasts that droop or are withered or shrivelled.

Although it’s clearly problematic for the male gaze to be applied to a girl’s view of herself and those around her, In Praise of Hatred still has much to recommend it. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts, whether you’ve read it or would like to (or not). And have you seen this problem of the male gaze in other books where men write from a female perspective?

There are 6 comments

Sounds like the book tries to take on some important issues. I like your test! I must say I can;t think of any books I have read lately written by men from a female point of view. I actually tend to avoid them consciously or not, because of the problems you mention.

It certainly does, Stefanie, and I think it’s worth reading for that reason, notwithstanding the breast obsession 🙂

Isn’t it a lot of misery for one person?

I love your test. I’m going to do it too, its a good idea because I really think that men are more obsessed with breasts than women.

Yes, a lot of misery, Emma! The book really conveys very effectively the stifling world and difficult choices of the main character. And yes, please let me know how the “breast test” works out with other books you’ve read 🙂

Hey Andrew,

Always glad to get your posts, no matter when. Disappointed I will not be able to get my hands on the new short story. Maybe someday? Was enjoying the review until you mentioned the breast thing. Will try and read the book anyway. Men are men. I sometimes think their penis should be on their chests.

As usual, your friend.

Jennifer

Haha, I like that image of the penis on the chest, Jennifer! It certainly does seem to be pretty central in how most men see the world 🙂