I recently visited Ceuta, a piece of the north African coast that belongs to Spain and is hence part of “Europe”. It was a very strange and disturbing experience to cross that border so easily just by showing my British passport, when many people with different-coloured passports die trying to do the same thing.

Here’s a photo I took of the border fence. The houses to the left are in Spain; the hillside to the right is in Morocco. There’s also a small village on the Moroccan side, just out of shot. When I was there, a Moroccan man was calling out to his family on the other side, who shouted back at him across the razor wire.

I’d spent three months in Morocco, and the difference in quality of life on the other side of the fence was palpable. Ceuta is very much a European city, with the usual pedestrianised boulevards, cafes and shops. There’s none of the desperation and poverty that I saw throughout Morocco. The GDP per capita there is about $20,000, similar to that of Spain as a whole, and about five times that of Morocco.

International borders preserve those differences of wealth. Those of us with the right passports get to come and go as we please, enjoying a relatively good quality of life; those of us born under the wrong flag get penned in, unable to travel to more prosperous zones without visas that are costly and difficult to obtain. If they are slaughtered in great enough numbers, we may, with much grumbling and resentment, allow limited numbers of them to join us. Otherwise, they’re expected to remain on the other side of the fence.

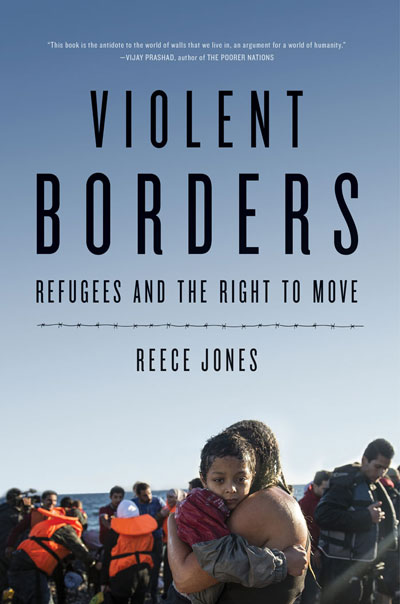

Those who refuse to accept this state of affairs die in large numbers as they attempt to cross increasingly militarised borders. I learnt a lot of new things about the history of borders and the violence inherent in them as I read the excellent book Violent Borders by Reece Jones.

Jones argues that the very existence of borders produces the violence that surrounds them. He identifies five types of violence resulting from borders:

- Overt violence by border guards and border security infrastructure: sometimes, people are shot by border guards, get impaled on a razor-wire fence, etc. Indian border guards, for example, have shot more than a thousand Bangladeshis since 2000.

- Blocking off the easy crossings forces people to take tougher routes across deserts or seas, in which thousands die.

- The threat of violence necessary to limit access to a particular enclosed territory.

- Economic, structural violence: depriving the poor of opportunities. In many cases, of course, this leads to actual violence and death (e.g. starvation).

- Violence to the environment through the construction of walls, etc.

He points out the problem with differentiating between refugees (deserving) and economic migrants (undeserving).

In the current system, a refugee fleeing political persecution is more legitimate than a migrant fleeing a life in a filthy, crowded, disease-ridden and dangerous slum where the only option is to work long hours in a sweatshop for very low wages. Focusing only on the limited, state-defined term refugee renders other categories of migrants, who are moving for economic or environmental reasons, as undeserving of help or sympathy.

Europe’s borders are the most dangerous in the world. Frontex has estimated that one out of every four people attempting to enter Europe by boat dies en route.

An interesting thing about borders is that, in their current form, they are very recent. For most of human history, boundaries between states and empires existed, but people moved across them quite fluidly. Ideas like citizenship and mandatory passports for entering certain territories only emerged in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As Jones says:

Prior to World War I, the only time passports were required was in times of war.

Even for most of the twentieth century, borders were much less heavily guarded than they are today, except in times of war and with obvious exceptions like the Iron Curtain.

So why the difference now? Jones points to growing global inequality as a key factor:

As late as 1700, wealth was spread relatively evenly around the world, with the wealthiest states wealthier than the poorest by only single-digit percentages.

In those days, the greatest inequality was within nations, not between them. There was less reason for people to want to migrate, and less opportunity. And when they did migrate, there were countries like the United States that had a need for labour and people to work the land, and actively encouraged new settlers.

Today, on the other hand, Norway has a per-capita GDP of $97,000, while the Democratic of Congo’s is $300. With such huge inequalities, it’s natural for the poor of the world to migrate in search of opportunity, and with improved transportation and communications, it’s easier for them to do so. The only way to stop them is to work seriously to achieve greater global equity. But who in rich nations really wants to do that? So instead, we build higher walls. Whereas in 1990 only 15 countries had walls or fences on their borders, by 2016 that number had risen to almost 70. And, as we all know, more are being planned.

But while people are penned in by borders, corporations have the right to cross as many boundaries as they want. If governments enact laws to rein in companies and protect their workers, the companies can just go elsewhere. The result is a race to the bottom. And, of course, when we need global cooperation on things like climate change, individual states fight for their own interests, not for the interests of the human race as a whole.

In Violent Borders, Reece doesn’t restrict himself to international borders. He draws relevant parallels between international borders and more local forms of “walling off” such as the enclosures of common land in England in the Middle Ages. The common thread in all of the cases he points to is the exclusion of some people for the economic benefit of others.

Another thing I didn’t know: for most of history and until the end of World War II, the territorial waters of most states extended just three nautical miles from their coasts, and 95% of the oceans were open to free movement. It’s only more recently, as the oceans and the land underneath them have become important resources to be plundered, that states have aggressively extended their territorial waters and “enclosed” more than 40% of the world’s common oceans.

Jones ends by calling for the abolition of borders. If we truly care about reducing global inequality and ending poverty, this would do it. He looks at the progressive extension of citizenship in the USA and elsewhere to include previously excluded groups like women, the poor, and those of different races, and he sees the inclusion of those who happened to be born elsewhere as a natural evolution of that trend.

One day, denying equal protection based on birthplace may well seem as anachronistic and wrong as denying civil rights based on skin color, gender, or sexual orientation.

He also points out that, even when there are no restrictions, fewer people move than you might think. The US state of Maryland has double the average income of neighbouring West Virginia, and there’s free movement between the two, but Maryland is not inundated by economic migrants. Within the European Union, the elimination of border controls between nations has had very little effect on migration:

Only about 2 percent of EU citizens live and work in another EU member state. This figure has remained stable for about thirty years, and even the EU eastward enlargement has had little effect on it.

So we probably wouldn’t be inundated with the floods of refugees you’d expect. We might actually start to make a more serious attempt to deal with global poverty, since we’d have a bigger incentive to make people’s lives less hellish. And we wouldn’t have to live with the uncomfortable thought that our privileged existence depends on the existence of places like Ceuta and its razor-wire fence.

And here’s another thought—we’ve been bleating for years about the pension deficit and the lack of young workers to support the ageing population. Wouldn’t an influx of young, hard-working tax-payers be the answer to our prayers? If not, why not?

When I was in the small town of Khamlia in the deserts of southern Morocco, I got talking to someone who said his brother lived in Spain, and his father had been unable to visit him for years because he couldn’t get a visa. When I was in Albania, a young classical musician beseeched me to help him move to the UK. In Budapest’s Keleti train station in the summer of 2015, I met IT specialist, small business owners, teachers, parents and children from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and other nations, sleeping on the floor while they waited for dithering European politicians to decide what would be done with them.

What all these people wanted was so simple, and yet they were denied it based on a lottery of birth, while I can travel to and from their countries with ease. If I am asked to justify this on ethical grounds, I come up short. The idea of removing borders scares me slightly because of all the unknown consequences, but when it comes down to it, there is no logical or moral justification I can think of for keeping them.

What it boils down to is: “I am privileged, and my privilege is comfortable. In order to retain it, numberless others must suffer in poverty or die trying to escape it. But we should let a few of them in to salve my conscience, and I’ll make a big show of tweeting #refugeeswelcome to distinguish myself from those awful Brexiteers and Trump supporters.” This doesn’t seem very defensible to me.

Doubtless some will point to security as a justification. I’m writing this the day after a suicide bombing in Manchester in which 22 people died, and early reports say the bomber was a British-born man from a Libyan family. Fear of Islamic fundamentalists has prompted much of the wall-building of recent years.

But I honestly don’t think that walls are the answer. On the contrary, they may be making things worse. Dealing seriously and honestly with the global inequities that divide us seems like a better plan. The broader point, to me, is that we can’t live securely in a world of such huge inequalities. It’s just not sustainable. Either we tolerate increasing militarisation and expansion of the security state with increasing violence at its borders (and, despite that, still never being truly secure), or we face up to the fact that maybe things need to change at a very fundamental level.

What do you think? Can you think of a good logical justification for the existence of borders? Do you like the idea of a borderless world and complete freedom of movement, or does it unsettle you? Let me know your take!

There are 2 comments

Very interesting essay. You brought up the point of income disparity and I think that’s a pivotal point. We have to come to the point where it’s beneficial to everyone to work towards the common good. The U.S. Is a huge melting pot of people from all over the world. This has enriched our culture, and now it’s being threatened by fear. People become alarmed by anything they perceive as a threat to their comfortable lives. They’re afraid of terrorism, which causes them to act illogically. Historically, weather patterns caused mass migrations as well as causing new religions to form. ( the old gods weren’t protecting the any longer) I don’t think migrations will go away. I feel we need to work with this reality in an inventive way, but certainly not high walls. Birds are more fortunate than we are. They fly back & forth whenever they choose.

Hi Barbara,

You’re absolutely right when you say that it’s beneficial to everyone to work towards the common good. For one thing, climate change will force our hand, whether we like it or not. And if we don’t do it, the planet will be a very unpleasant or even impossible place to inhabit, and migrations on a much larger scale than today’s will certainly become a fact of life. It’s interesting that you mention the birds—I often think about them and their freedom of movement! But one interesting point in the Violent Borders book is that many other animals suffer because of our human walls and borders, for example getting boxed into a smaller territory, or having the ecosystem destroyed by walls that block water flow, etc.