This post is part of a series in which I publish stories and articles I wrote exactly ten years ago. This one is a profile I wrote at Columbia Journalism School of Catholic peace activist Tom Cornell. For more stories in the series, click here.

December 1, 2002

It’s hard to know what gives Tom Cornell more pride – the time the Pope invited him to read the gospel in front of 40,000 people at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, or the time he was arrested in Washington D.C. for trying to occupy the Capitol on behalf of the unrepresented peoples of the world. The photographs lining the wall of his ramshackle communal farmhouse in upstate New York highlight all the apparent contradictions of a man who has devoted a long life to marrying devout Catholicism with a passionate belief in social justice. He shares common beliefs with liberals and neo-conservatives, communists and cardinals, and he harshly criticizes all of them. Yet as he puttered around on the farm, reminiscing about the past and arguing his vision for the future with undimmed fervor and wicked humor, the contradictions gradually melted away into consistency, and it was the ideological labels that began to look rather absurd.

Cornell made a brief, tongue-in-cheek effort to define himself as he sat down to dinner last week with the 13 members of the Catholic Worker community farm in Marlborough. “Tom Cornell, minister, public speaker, raconteur, bon vivant,” he said, before his face creased up into a broad smile and he added in a mock Irish brogue, “and horse’s arse.” It was hard for him to take himself too seriously, especially on that night. The members were celebrating Joan’s 70th birthday with a meal of soup and bread. Joan had asked not to be given any presents, so the only concession to materialism was a trio of party candles stuck into the loaf.

Voluntary poverty has been a principle of the Catholic Worker movement since it was founded in New York in 1933 by a converted communist, Dorothy Day, and self-educated French peasant Peter Maurin. Instead of doling out charity to the poor, they chose to live with them in communal ‘hospitality houses’ where anyone could come in and get a free meal and stay for as long as they wanted. To pay for their provisions, Day and Maurin began publishing and selling copies of the Catholic Worker newspaper for a penny a copy. Today the circulation is 80,000, and the price is still a penny a copy. Extra donations from readers provide the $500,000 annual budget needed to support the newspaper, the two hospitality houses in New York City and the Peter Maurin Farm in Marlborough. Nationwide, there are 185 Catholic Worker communities, although there is no formal organization linking them together.

The Catholic Worker has had a strong effect on Cornell’s life, at the same time as he has profoundly influenced the Catholic Worker. Now 68, he still regularly attends religious meetings and peace rallies, his graying hair and slightly bent frame marking him out as an elder statesman, until his piercing brown eyes and proudly jutting chin suddenly recall the young man surrounded by FBI agents in fading black and white photographs. “You can’t tell the story of the Catholic Worker without talking about Tom,” said volunteer Amanda Daloisio, 27, as she went into the kitchen of a Lower East Side nursing home to get leftover food for the Maryhouse hospitality house. “As I understand it, he was the right-hand man for Dorothy, and was often the voice of the Catholic Worker.”

After a Jesuit school education in Connecticut, Cornell first became involved in the Catholic Worker movement while studying at Fairfield University. The ideas in Day’s autobiography, The Long Loneliness, resonated with him. “To me, that was genuine Catholicism, there was nothing phony about it,” he said. He was particularly touched by her views on poverty. “I knew about poverty,” he said. “My father took 10 years to die. We couldn’t heat our apartment in Connecticut. I went into high school with one coat, a Robert Hall’s coat, and I got out of college wearing that same coat.” Cornell worked 60 hours a week in factories from the ages of 16 to 18, and then worked his way through college. His father was a World War I veteran but received no benefits in those days. His mother found jobs, but she never made more than $55 a week in her life. “She was educated and skilled, but she was a woman,” he said.

Cornell found in the Catholic Worker movement the combination of faith and social conscience he had sought. Deciding to volunteer while still a student, he first arrived on the Lower East Side on a warm April day in 1953. “It was appalling,” he said. “The 3rd Ave El was still there, so it was dark and noisy, with hundreds of thousands of people milling around. There was a smell of tuberculosis, of rotting lungs.” He found his way to the Catholic Worker house just off the Bowery and began the 50-year association that would shape his life.

After leaving university he asked Dorothy Day for a permanent job with the Catholic Worker, hoping for some minor involvement in the newspaper side of the organization. “She said, ‘OK, here’s your desk, and here’s your galleys. You’re putting out the paper.’ I was managing editor of the Catholic Worker,” he said. When he protested that his only experience was with the high school literary magazine, she replied, “Well, here’s a copy of the proofreaders’ signs, that’s all you need, you just have to learn to do this. And you go to the printer with these galleys and they’ll teach you.” Cornell said that this was typical of Day’s style. She had very strong opinions on the direction the movement should take, but gave great responsibility to people whom she trusted to follow that vision. Cornell soon began taking speaking engagements and signing petitions on Day’s behalf.

While working for the Catholic Worker, Cornell soon became involved in the broader progressive movement. In the late 1950s he made several trips to the shipyards at New London, Conn., with other peace activists like A.J. Muste and Dave Dellinger, to board the newly built submarines and claim them for the Family of Man. “Typical pacifist hyperbole,” Cornell recalled with a smile.

The non-violent direct action continued throughout the 1960s, with Cornell steadily taking a more prominent role. In 1963 he invaded the Capitol, an event captured in the framed Washington Post photograph of the arrest on his wall. Then in 1964, he got together with other radical Catholics, like Jim Forest and Father Dan Berrigan, to found the Catholic Peace Fellowship in protest against the Vietnam War. “I couldn’t have asked for a better co-worker,” said Berrigan. “Tom was intelligent, resourceful and courageous. He took a strong stand against the war and stuck to it.”

Cornell left the Catholic Worker house for a few years after marrying another member, Monica, in 1964, and having two children, Tom and Deirdre. However, his connection to the Catholic Workers remained strong, and his activism continued. In August 1965, he became one of the first people to burn his draft card with a group of other protesters in Union Square. Bruce Porter, then a reporter on the peace beat for the New York World-Telegram and Sun, recalled the event: “I remember as they were about to get them lit, a group of counter-protesters sprang up with fire-extinguishers, and just doused them. But they got them lit in the end. And then they got arrested.” Porter covered Cornell’s other actions in the peace movement in those years, and remembered him as “a very heartfelt, conscience-driven guy. I found him interesting because he didn’t have that messianic, blind expression – he was very rational and had a real sense of humor.”

Although Cornell would spend six months in jail for burning his draft card, and the struggle against the Vietnam War would shape the next eight years of his life, the events that had a greater effect on him took place earlier that year, in March 1965, in Selma, Ala. He still struggled to control his emotions as he described the marches, the murders of fellow civil rights workers, and Pres. Lyndon Johnson’s speech to Congress shortly afterwards. “When we heard Lyndon Johnson saying in his Southern accent, ‘We shall overcome,’ we knew immediately that we had won,” he said. “There we were, these old hardened radicals, with tears pouring down our faces.”

However, Cornell found that racial and social injustice persisted long after the victories of the civil rights movement. He remained a critic of the establishment, while at the same time gradually becoming more accepted within it. He helped Pres. Jimmy Carter to negotiate the Panama Canal Treaty in 1977, receiving in return a letter of thanks and an official pardon for his earlier criminal convictions. He became an ordained deacon and advised the conference of bishops on various peace and justice issues, such as their position on the reintroduction of draft registration in 1980 and the Peace Pastoral condemning nuclear deterrence in 1983. His proudest moment in the church came with his invitation to the Vatican as part of the jubilee celebrations in 2000.

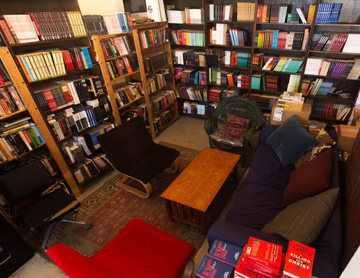

Cornell has lived in Catholic Worker houses for almost 50 years now, apart from the brief spell in a private apartment just after he got married. He and his wife Monica set up a hospitality house in Waterbury, Conn., in 1982 and lived there for 11 years before moving to the Peter Maurin Farm. As with all Catholic Worker houses, it is difficult to tell which of the 13 members of the community are ‘workers’ and which are ‘guests.’ In fact, they don’t even have words to describe the distinction.

People can come to any Catholic Worker house and stay as long as they want. Cornell pointed to another member of the community, who was sitting apart from the others and staring blankly at the wall. “That’s Slim,” he said. “His mother brought him in one day and said, ‘I just need someone to look after him for a while. He’s a bit touched. I’ll be back to pick him up on Monday.’ That was in 1937.”

Apart from Slim, Cornell is one of the longest-serving members of the Catholic Workers. “Tom is a bridge to an earlier era, a force of continuity,” said Robert Ellsberg, a former editor of the Catholic Worker newspaper and now editor in chief of publishing company Orbis Books. “His example of raising a family and transmitting his values to his own children is important. It’s not easy to do. A lot of people retire from that difficult and dangerous life when they have a family and responsibilities, but Tom’s stuck with it. That says a lot.” Cornell’s son, Tom Jr., also lives on the farm, and his daughter Deirdre is training to be a missionary in El Salvador.

Cornell, however, is not content merely to let the next generation take over. He is still full of clear ideas and plans about how to continue trying to make the Catholic Church more socially progressive and a stronger advocate for peace. With typical intellectual dexterity, he uses the ‘right to life’ argument to support his social justice agenda. “The right to life is always framed as opposition to abortion, euthanasia, suicide, and it does include those things,” he said. “But it means more than that. It’s also the right to the means of life. And the means to life include job training, education, a decent job doing good work, and recompense for that labor sufficient to raise a family. A living family wage. That’s a right-to-life issue.” He was keen to distinguish himself from conservative right-to-life advocates, who “are very concerned about people. . . until they’re born.”

He was also firmly against being associated with liberals. “People think that radical, that means liberal but more so,” he said sadly. “No it doesn’t! It means you start from different premises. You get to the roots of a problem, and those roots may be different. You wonder, with the American liberals, what’s their agenda? Their agenda is a bourgeois agenda. It’s not concerned with working people. It’s not the agenda of the world’s poor. It’s basically saying, ‘I want to be able to get my rocks off, no matter what.’ Well if that’s liberalism, you can shove it.”

As for the Catholic Worker movement, he does worry that it is becoming less coherent, as some houses start to hire paid staff, and others are no longer even Catholic. He wants to travel around and tell stories about Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, to try to pass on their values to the next generation, but he finds there is too much still to do and not enough time to do everything.

He will be spending Christmas in Baghdad, for example, on a mission of solidarity with the victims of American bombing and sanctions. From there he will travel to Rome to lobby the Vatican to take a strong stand against the war. “We’ve given a blank check to every government to wage every war since the fourth century,” he said of the church. While others became disillusioned, Cornell’s belief in personal responsibility led him to take it upon himself to try to reverse 1,600 years of history. “Real change can only come at the individual level,” he said. “Each person has to take personal responsibility for the world around him, and do what he can to change it.” From flamboyant acts of civil disobedience to the daily grind of the soup kitchen, Cornell has done what he could to make the changes he believed in. And he’s not finished yet.

There are 5 comments

Cornell is an intriguing character. Though I am not a believer in Christianity I find many of its principles noble. It seems that the Christian worldview would go hand in hand with such activism.

Hi Brian

I’m not a believer either, but I am fully signed up to most of its basic principles. Theoretically you’re absolutely right – the Christian worldview should go hand in hand with such activism. In practice, unfortunately, it’s not always the case…

Nice profile. Too bad Tom Cornell raised Tom Jr. to be a rapist. So many rapists in the Catholic Worker.

Hi Vee, I’ve never heard of any rape allegations, either against Tom Cornell Jr. or the Catholic Worker in general. Do you have some more information you can share? It’s not that I don’t believe you, but I’d like to see some corroborating evidence for such a serious allegation. Feel free either to comment here or to email me using my “Contact” page.