After my unintended gatecrashing of a class with Derek Walcott earlier in the day, this was an event I was actually allowed to attend. It was an interview with two major Caribbean writers, Austin Clarke and Earl Lovelace, followed by readings from their latest work.

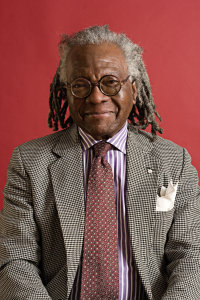

First up was Austin Clarke, a Barbadian novelist and short-story writer who has lived for most of his life in Canada. He named George Lamming’s Pleasures of Exile as his favourite Barbadian book, and the short story collection There are no Elders as his favourite of his own books. He said Lionel Hutchinson was the most underrated Barbadian writer.

I was interested to hear that Clarke never wanted to be a writer. His ambition was to go to Canada, study law and economics, and come back to Barbados to run the country. At another point he said his ambition was to be a lawyer, because in his day the men with the most style were all lawyers. Unfortunately the interviewer didn’t follow up and ask how and why he changed his mind and ended up being a writer.

I was interested to hear that Clarke never wanted to be a writer. His ambition was to go to Canada, study law and economics, and come back to Barbados to run the country. At another point he said his ambition was to be a lawyer, because in his day the men with the most style were all lawyers. Unfortunately the interviewer didn’t follow up and ask how and why he changed his mind and ended up being a writer.

He also said that if he’d stayed in Barbados, he’d probably have been a teacher, not a writer. Almost all of the well-known writers of that generation went abroad, to England, Canada or the USA – some for a few years or a decade, others permanently. Barbados is a tiny island, and there simply isn’t a big enough book-buying public here to support writers. This is something George Lamming also talked about when I went to a talk he gave here a couple of years ago:

Lamming ended by talking about the difficulty of forming a national literature in such a small country (about 270,000 population, of which the book-reading population is much smaller). He asked the question, “Can you have a national literature if you don’t have a book-reading class?” The sovereignty of a literature depends, he said, on books belonging to the whole people, being talked about by people, and the implication he left us with was that this is not happening in Barbados.

It’s sad, to me, and made me wonder if more could be done to link the literature of the different islands together. The book-reading population may be small in Barbados, and in St Lucia, and in Dominica, but across the whole Caribbean you have 40 million people, which is surely big enough. Yes, language is an issue, but even in the English-speaking Caribbean alone there are 5 million. Anyway, I know it’s not easy, and that these are small islands with limited resources, so much of the focus has to be on economic development. But it’s sad to hear a writer say he had to go somewhere else in order to be a writer.

Clarke said there was only one book in his household growing up, the Bible, but his father was away a lot and his mother used to invite other women over and they told stories to each other, mostly horror stories. So his early influence came not from books but from oral story-telling, which I thought was interesting. I’ve always thought of reading as essential for any writer, but it shows there are other ways (although Clarke is also a well-educated man and would have read a lot later in life).

He then read from his work-in-progress memoir, but to be honest I found it quite difficult to follow. He’d left his reading glasses in Toronto and had to borrow a pair, and he was clearly struggling to read. I empathised with him, knowing how difficult it is to give a reading, so I’ll reserve judgement on the memoir until it comes out. I think it’s going to be called Membring, from the shortened form of “remembering” in Barbadian spoken language. For now I bought a copy of Amongst Thistles and Thorns, which I got him to sign, and am looking forward to reading.

One thing I found disappointing was the lack of any opportunity for audience participation. I’m not a big question-asker myself, but I do like the way it breaks things up and introduces other perspectives: some wacky, some long-winded, but some interesting.

Another observation: so many of the big-name Caribbean writers are very old now. Clarke is 77, Lovelace 76, and Walcott 82. Others like George Lamming, V.S. Naipaul and Kamau Brathwaite are of a similar age. Who are the younger writers? I’m sure there are some very good ones, but they don’t seem to have such a high profile. Maybe I’ll find out more as the Bim Literary Festival continues…

For a roundup of other posts in my series on Bim Literary Festival 2012, click here.

There are 14 comments

When I was studying Francophone literature, we had a Caribbean classification, for writers like Marysse Conde (who is wonderful). I can quite understand that the tiny population of Barbados doesn’t support a flourishing book market, but the island community might. Still, there are so many problems that writers face, it’s a miracle sometimes that any ever get published! Oh but the poor guy without his glasses – that must have been a little painful. And interesting that those writers are all so old. I do hope there is a new generation growing up, but perhaps they leave the islands early and head to the mainland, becoming subsumed into a larger culture but still with particular native concerns?

Hi litlove,

Yes, I’ve been meaning to read Maryse Conde for a while now. Do you have a particular recommendation? I was thinking of Crossing the Mangrove, but would love to hear your views.

I think you’re right that they leave early and go to either the UK or North America, but that happened with the older generation too and they were still known as West Indian writers. It could be that immigration has become more difficult over the years, and those who stay find it difficult to attract international attention. There are probably a lot of factors, but it did strike me as strange. When you think of the most famous writers in most countries, they’re usually mature but a range of ages. There are of course plenty of younger writers, but none who’ve reached the same heights (as far as I know).

Yes, Crossing the Mangrove is a great place to start. Or else I recall very much enjoying I, Tituba, Witch of Salem (at least, I think that’s the translation – Moi, Tituba, sorciere in French). I would love to know what you think of her.

Thanks! I also heard good things about I Tituba (yes, you have the right translation, or at least the one I’ve seen before). I wasn’t so interested in the subject matter, though – I’ve read quite a bit about the Salem witch trials before, and was more curious to read something set in Guadeloupe. But if I like Maryse Conde’s work, which it sounds as if I will, I’ll probably get to it in the end!

Austin Clarke is one of my favorite writers & yes, there are many “younger” writers from the Caribbean out there. Check out the web sites for Calabash, Bocas and my own: https://geoffreyphilp.blogspot.com/.

Peace,

Geoffrey

Hi Geoffrey,

Thanks for visiting! I hadn’t read anything by Austin Clarke before, but am looking forward to reading Amongst Thistles and Thorns. Do you have a particular favourite of his that you can recommend?

I didn’t mean to imply that there aren’t any younger writers from the Caribbean – it was more that the older ones have a higher profile (to me, anyway). But perhaps that’s because I’m from London, and the people who are high-profile in London are not necessarily the same as those who are high-profile in their home region. Thanks for the links – I love your site, with the photos on the front page linking to the posts! Lots of good info there to explore too. I know Calabash, but Bocas was new to me, so thanks for letting me know.

My favorite was Growing Up Stupid Under the Union Jack.

Re the Walcott workshop. I’ve been to several Walcott workshops and some times he has been cruel and sometimes very kind.

Similarly, I’ve been to readings where he has been on fire and sometimes phoned it in.

He can be very tempermental, which is why I prefer to stick to his books and enjoy his genuis.

Peace,

Geoffrey

Hi Geoffrey,

Thanks very much – my wife also recommended that one, so I’ll have to track it down and read it next (she no longer has her copy).

Interesting to hear about Derek Walcott – since I wrote the piece I’ve heard from other people that he can certainly be temperamental. I spoke to one of the other people in the class a few days later and when I said how shocked I was, he shrugged and said “That’s Derek Walcott, isn’t it?” I suppose if I’d known more about his personality beforehand, it would have been a different story, but I went there just having read a few poems and knowing nothing else about him. I still think it’s a shame he has to be that way, but I think your plan is the best – stick to his books and enjoy his genius!

My reaction to Walcott is almost like a reaction to a parent, “What are your going to do?” He is who he is and there is no changing it.

While it doesn’t excuse his sometimes irascible moods, I can also tell you that one night in MIami a group of us were at an expensive restaurant and I said I wasn’t hungry, He said “Sure you are,” and he shared half of his meal with me.

What are you going to do?

That’s a lovely story, Geoffrey! Thanks for sharing it. It’s very interesting that you bring up the analogy of a parent. It got me thinking about Walcott in a slightly different light, as a kind of stern, traditional, “tough love” parent. From what I’ve seen so far, that model seems far more prevalent here than it is in London, which could partly explain my reaction – maybe it’s partly a cultural difference. Because I’m used to a more nurturing model, his methods came across to me as cruel, but maybe there was a genuine desire to help hidden away there beneath the abuse. And maybe people who grew up getting licks and blows would have taken it much better.

Anyway, you’re right that he’s not going to change, so what are you going to do?! Interesting to see, and reactions like yours have really got me thinking and brought a new angle to it. Thank you!

Andrew, the sad part is that Walcott probably doesn’t think that he is being “cruel.” He is also behaving in a way that many of the teachers at my former high school, Jamaica College (you can wiki our history) would have condoned.

In a way, we have become so desensitized to violence in all forms that his behavior seems “normal.” The apocryphal toad in boiling water.

I’m not saying that writers don’t need to have a thick skin– a particularly bad review of my short story collection shook my confidence for months until I recovered.

But sometimes them should take it a little easier pon the yout’

Peace,

Geoffrey

Hi Geoffrey,

I looked up Jamaica College and it does look like one of those highly traditional schools. I can just imagine the teaching methods. I guess DW would have had a similar upbringing, so you’re probably right that he doesn’t think of it as cruel at all.

I know what you mean about bad reviews – writers get rejection and criticism all the time, so we can’t be too sensitive. It’s part of putting work out into public view. But I’m not sure that there’s a way around that, or that harsh treatment will “toughen us up”. Bad reviews just hurt, no matter who you are. My view is that people can help not by piling on the criticism, but by building up the writer’s confidence (or, in other words, taking it a little easier pon the yout’!)