My thoughts on Funes, His Memory, aka Funes the Memorious, a short fiction by Jorge Luis Borges about a man with an infinite memory.

Haven’t we all wished for a better memory sometimes? One of the reasons I started this blog was to help me remember the books I’d enjoyed reading but whose details continually slipped from my mind. When I think of all the knowledge contained in the hundreds of books I’ve read and the tiny proportion of it that I’ve retained, I mourn. And as for the events of life, that’s even worse. A few things stick out, but so much is lost forever.

In his short fiction “Funes, His Memory” (often translated as “Funes the Memorious” in other editions), Jorge Luis Borges explores what it would be like to have an unlimited memory. It’s not as pleasant as you might think.

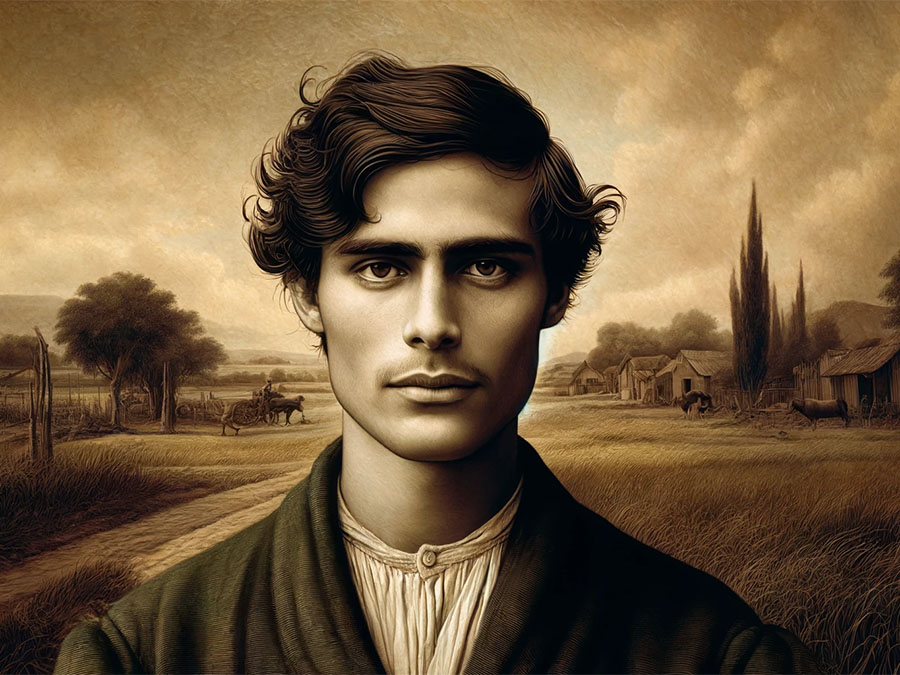

The man with the unlimited memory is Ireneo Funes, a young Uruguayan from a small country village, and the narrator of the story is a man who meets him just a few times. The narrator’s memory, unlike that of Funes, is far from perfect: he remembers and tells us all kinds of irrelevant details but has forgotten much of the conversation with Funes that is the main thrust of his story.

“I will not attempt to reproduce the words of it, which are now forever irrecoverable. Instead, I will summarize, faithfully, the many things Ireneo told me. Indirect discourse is distant and weak; I know that I am sacrificing the effectiveness of my tale.”

Funes suffers no such limitations. He remembers absolutely everything.

“With one quick look, you and I perceive three wineglasses on a table; Funes perceived every grape that had been pressed into the wine and all the stalks and tendrils of its vineyard. He knew the forms of the clouds in the southern sky on the morning of April 30, 1882, and he could compare them in his memory with the veins in the marbled binding of a book he had seen only once, or with the feathers of spray lifted by an oar on the Rio Negro on the eve of the Battle of Quebracho.”

It sounds like a gift, but it quickly comes to look more like a curse. Remembering everything and perceiving all the tiny differences between objects makes it impossible for Funes to generalise. A word like “dog” makes no sense to him because he remembers every dog he’s ever seen and how different they each were from each other, and even how the same dog appears and behaves differently at different times.

He invents his own numbering system, memorising thousands of simpler alternatives for numbers: “Instead of seven thousand thirteen (7013), he would say, for instance, “Máximo Pérez”; instead of seven thousand fourteen (7014), “the railroad”. He couldn’t understand why this random list of words was not a useful number system: even though it was quicker to say “the railroad” than “seven thousand and fourteen”, it didn’t communicate the numbers of thousands, hundreds, tens, etc. For him, it was simple to divide the railroad by the whale to get Napoleon, so the system was of no importance to him.

These difficulties hint at a larger problem: by perceiving and remembering everything in its infinite difference, Funes becomes unable to think.

“He had effortlessly learned English, French, Portuguese, Latin. I suspect, nevertheless, that he was not very good at thinking. To think is to ignore (or forget) differences, to generalize, to abstract. In the teeming world of Ireneo Funes there was nothing but particulars—and they were virtually immediate particulars.”

Linked to that, I think, is the idea of insomnia. In the foreword to this collection, Artifices (1944), Borges refers to the story “Funes, His Memory” as “one long metaphor for insomnia.” This feeling of endless teeming particulars crowding in the brain is what insomnia sometimes feels like for me. Sleep is a kind of ignoring and forgetting, a retreat from this teeming world into the general, abstract world of dreams. Funes is unable to do this, so he rarely sleeps. The conversation with the narrator takes place overnight, in total darkness.

Readers of other parts of my Borges Marathon (if there are any) may be noticing parallels with other Borges fictions at this point. I found myself thinking of “The Library of Babel“, in which the idea of an infinite library containing every possible book quickly comes to seem more like a nightmare than a dream. In the chaos of infinite books, all meaning is lost. To make any sense of the world, we need to select from it, retaining some things and discarding others. An infinite library, like an infinite memory, encompasses everything but prevents us from perceiving patterns and creating order.

Like many Borges fictions, this is less of a traditional story than a fictional exploration of an idea. There is no plot as such: things happen, but more to set the stage for the exploration of the idea. Funes has no narrative arc, no goals or character development in the conventional sense. When he has served his purpose, Borges disposes of him callously in a quick final paragraph: “Ireneo Funes died in 1889 of pulmonary congestion.” The narrator, too, seems like a mere vehicle for delivering the story, with little life of his own.

I recognise that some readers may find this kind of thing may be frustrating, but I find it very effective. Borges overturns traditional ideas of story-telling and gives us something different, something fresh and surprising. I’m pulled through the fictions not by wanting to find out what happens to Funes or the narrator but by wanting to see where Borges and his spiralling imagination will take us next.

There are 14 comments

Excellent! Another one by Borges I want to read. Well, anyway, what wouldn’t I like to read by him, lol?

OMG, of course I have read it, as I read all of Ficciones. Here is my take on that story: https://wordsandpeace.com/2021/12/23/ficciones-by-jorge-luis-borges-the-garden-of-forking-paths/

I love that in your first comment you forgot that you’d read a story about a man who never forgets anything 🙂 I’ll go and read your post now – thanks for the link!

???

“Borges overturns traditional ideas of story-telling and gives us something different, something fresh and surprising.” I think you might have pinned down there what I love about Borges!!

It’s a wonderful characteristic, isn’t it? I remember the first time I read the Collected Fictions, years ago, feeling my mind opening up to new possibilities in storytelling all the time. Some work better than others, but there’s always something to think about. I loved this one.

Not being able to forget would be horrific. I am reminded of Solomon Shereshevsky who had such a good memory people thought he remembered everything, though he was studied so much they found this was not the case. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solomon_Shereshevsky Memory is such a fascinating thing.

I get very frustrated when I forget things, so I’ve always wanted a better memory. But you’re right that forgetting also serves an important purpose. The more you think about it, the more of a nightmare a perfect memory comes to seem. But I’d still like one that’s just a little more functional 🙂

I am not Irineo, I read Ficciones and I have definitely forgotten everything, possibly because I never blogged or wrote about it, making me want to read everything by Borges now! Like Kaggsy, you nailed it with your comment on how innovative he is while respecting the storytelling craft. His obsessions -memory, libraries, time-, are definitely mine and I suspect that’s why his philosophical and yet literary written stories are always a fabulous read.

Hi Silvia, Yes, I’m nothing like Ireneo! I’d like to be a little more like him, without approaching the kind of perfection that plagues him. That’s a big reason why I’ve been blogging so long, as a way of remembering all the wonderful (and sometimes not so wonderful) things I read. I first read Borges years ago, and as I reread the stories now, some are very familiar but others feel almost like I’m reading them for the first time.

Elisa Gabbert’s essay collection, Any Person is the Only Self, contains an essay that explores real life examples of people with this condition – hyperthymesia. Naturally she gives a nod to Borges’ story in it. You’re right it’s a curse and I love what you say about the way it prevents us from seeing patterns and creating distinctions. It must also overwhelm the project of creating a self, which is surely delineated by our choices, including the choice of memories and events and information. It’s intriguing that Borges creates his writing persona precisely by means of stories that refuse the choices of plot and story, reaching out instead to unimaginable infinity and the impossibility of meaningful constraint. Lovely review from you as always!

Oh, thanks for this – I didn’t know there was an actual condition with that name. And I looked into that essay collection and it looks very interesting too. Another one for the TBR list!

That’s a great observation about the role of memory in creating a self. My sister and I have very different memories of the childhood we spent in the same house, experiencing largely the same things. The memories we retain are those that reinforce a story about our version of events, and they fit a pattern dictated by our respective personalities.

I find it very interesting that you frame it as a choice because I’ve never thought of it that way. I tend to think of the personality already existing and influencing the memories we store or discard, but I’m fascinated by the idea that it could, instead, be a conscious choice, a project of self creation. I need to think about that some more. Thanks for the thoughtful comment!

What an interesting examination of this installment in your project. I find the idea you raise about how callously, expeditiously Borges disposes of his “vehicle” of story, dispatching him with a single line. It reminds of a talk I heard from Annie Proulx about her novel Barkskins, where she spoke about how abruptly a couple of her characters died in that novel (it’s a veeerrrrry long novel, that’s not a spoiler) and she said, well, it was over just that quickly. So there goes Borges’ character: he doesn’t remember anything now, there’s nothing more to say about him really! (On a practical note, I quite enjoyed Julia Shaw’s book The Memory Illusion. And in a literary echo, Billy Collins’ poem “Forgetfulness” which is available online in full in a variety of places, in case you’ve…forgotten it.)

I think Borges must have enjoyed killing his characters like that because it happens quite a bit. Lazarus Morell, the antihero of the first installment of this marathon that I wrote back in 2009, also died of pulmonary congestion in a single, emotionless line. Other characters have met diverse fates, from gunshots to stab wounds to mysterious illnesses, usually delivered laconically. My favourite is Hakim, the Masked Dyer of Merv, who is trying to explain himself to an angry mob when Borges simply says: “No one was listening; he was riddled with spears.”

The theme behind it all, I believe, is human frailty. Most of the characters who meet these swift deaths have lived extraordinary lives and often enjoyed huge amounts of wealth, status and power. Borges seems to take pleasure in cutting them down to show that all these things are, in the end, temporary and illusory.

Thanks for the recommendations! The Shaw book seems hugely popular but somehow I missed it. Definitely sounds like the kind of thing I’d enjoy.