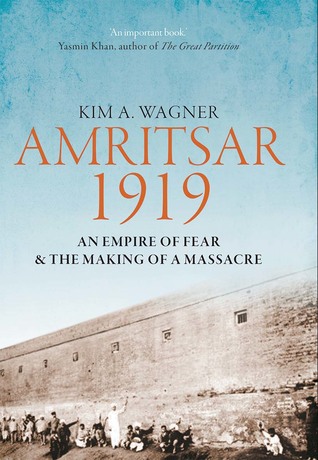

Why did British troops massacre hundreds of Indian civilians at Amritsar in 1919? This book explores the whole shocking story.

The Amritsar Massacre is one of those historical events about which I knew only the bare facts: British colonial troops massacred unarmed Indian civilians in a public garden.

After reading Kim Wagner’s detailed history, Amritsar 1919: An Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre, I now understand it in a deeper way: not just as a horrific and shameful event, but as part of a larger project of colonial violence.

What I like about the book is that Wagner tries to understand the real motives of General Dyer, who ordered and supervised the massacre, and of the other colonial administrators who participated or contributed. It’s easy to view men like Dyer as cartoon villains, but doing so lets the British Empire off the hook. It turns Dyer into an aberration, someone whose inexplicable brutality gave a bad name to an otherwise benevolent venture. That’s been a very prominent narrative about Amritsar in Britain for the last hundred years.

By seeking to understand Dyer, Wagner does not seek to excuse or justify his actions. The effect, instead, is to reach a deeper understanding of how the British Empire operated, how such vastly outnumbered colonisers were able to maintain power for so long over so many distant lands. And it has a lot to tell us about how state power still operates today.

First, the basic facts about Amritsar. On 13th April 1919, a peaceful crowd of several thousand gathered in a public park in the Indian city of Amritsar to celebrate a religious holiday and listen to political speeches. But the colonial authorities, spooked by recent rioting and violence in the city, viewed the gathering as the start of a rebellion.

Without any warning, Dyer’s troops fired 1,650 rounds into the densely packed crowd. The garden was surrounded by walls on all sides, with only narrow exits that quickly became blocked in the stampede to escape. As people scrambled to climb the walls, they were shot in the back. As they lay on the ground, they were shot. Bullets ricocheted everywhere. Hundreds were killed and thousands wounded. And Dyer gave no assistance to the wounded, instead enforcing a curfew so that many of the injured were unable to get help and died overnight.

After the massacre, the British instigated a violent and humiliating period of martial law in which, among other things, Indians were flogged and made to crawl in the dust on a road in which a British woman had been attacked a few days earleir. It was a time of collective punishment and violent retribution for the earlier riots.

Exemplary Violence

To trace the origins of the massacre, Wagner goes back to 1857, the year of the “Indian Mutiny”, in which the British reasserted control by a policy of inspiring terror in the local population through “exemplary violence”, in which hundreds were killed to teach the “rebels” a lesson.

One favoured technique was to strap captured rebels to a cannon loaded with gunpowder and blow them to pieces in front of crowds forced to watch the spectacle. Others were pursued to a river and given the choice of drowning or being executed by firing squad.

Again in 1872, after the Kuka uprising, the British unleashed brutal violence to suppress the threat and restore control. They strapped people to cannons and blew them to pieces, as in 1857, and they defended it as necessary for maintaining power in the Punjab: Deputy Commissioner Cooper said it was “the only way to strike terror into its semi-barbarous people.”

Wagner’s conclusion from this:

“British rule in India, in other words, was sustained by the application of exemplary violence, and this became one of the founding narratives of the colonial state in India after 1857.”

The story that Wagner then tells of Amritsar in 1919 is a continuation of this larger story, instead of an isolated event. He draws on multiple perspectives from both the British and Indian sides over the days and weeks leading up to the massacre, showing the fear and misunderstandings on both sides.

They became locked into a cycle in which the British, fearing another “Mutiny”, unleashed more repression, which made the Indian population protest what they saw as unfair measures, which confirmed the British in their impression of a rebellion, leading them to become even more repressive, and so on.

“The Man Who Saved India”

General Dyer thought he was doing his duty that day. He thought he was protecting a vulnerable British minority from a dangerous mob. Many in Britain thought the same—although Dyer was officially censured and stripped of his command, the Morning Post (a forerunner of today’s Daily Telegraph) took up a collection for “The Man Who Saved India” and raised £26,000, the equivalent of around £1 million today.

What’s particularly revealing about Dyer’s subsequent statements is this admission:

“I think it quite possible that I could have dispersed the crowd without firing but they would have come back again and laughed, and I would have made, what I consider, a fool of myself.”

In order not to lose face, he ordered the slaughter of hundreds of innocent civilians. But again, remember that Dyer is not an exception. He’s not a cartoon villain. Killing to avoid losing face may seem absurd or evil, but losing face is no trivial matter when you’re a tiny force trying to wield power over a huge population in a vast area. Face is pretty much all you have. Lose face, and the illusion of power disappears with it.

What comes across strongly in Amritsar is the fear and vulnerability felt at all levels of the British adminstration. They knew how few of them there were, how easily they could be overpowered, how essential it was to instill terror into the local population. Hence exemplary violence. Hence the Amritsar Massacre.

Given the thesis that Amritsar was part of a larger project of colonial violence, I’d have expected to see more about those other examples, to make it part of a whole. Wagner touches on other massacres in Africa and elsewhere, but doesn’t go into detail. It makes sense because fundamentally this is a book about Amritsar, but I thought it would have supported his argument to give a few more examples.

Overall, though, I found Amritsar 1919 to be a very well-researched, readable account of this important historical event. There’s lots of detail, but Wagner doesn’t get bogged down in it. There are personal stories from people involved in the events on both sides, and we really get to see things through their eyes. I’d recommend it if you’re interested in history or just want to understand the brutal realities of how small groups manage to wield power over much larger ones.

For another take on this book, see the always excellent Resolute Reader. Or click here to see more of my book reviews.

There are 4 comments

This brings to mind a long essay that I read on the weekend by Rinaldo Walcott, On Property. He’s actually writing about the link between the plantation system and sustained colonial violence and exploitation in the present-day but a lot of what he discusses fits with the situation you’re describing here. It sounds like the balance here, between documentation and personal experience, makes for an exceptional reading experience. Was it a recommendation from a reading friend, or part of some other research?

Oh, that Walcott essay sounds interesting! I’ll look it up. Yes, this was a very detailed history, giving lots of personal experiences of the massacre and the events leading up to it, but also giving plenty of context of how it fits into the broader picture of British colonial rule. I don’t think it was a recommendation, as far as I can remember. Amritsar is just one of those names I’d always heard thrown around as an example of the violence of empire, but I never knew the details, so I decided to remedy that. There are quite a few books out there because the centenary just passed, but this one seemed to get the best reviews, so I went for it. Glad I did!

The book sounds really good and intense. Or maybe your post is intense for me because I had not heard about this massacre before and my imagination immediately went to the horror it must have been to be trapped in those walls. I wish we could say things like that didn’t happen anymore.

Yes, it’s quite a horrific story. The book in general has that slight distance that comes from a historical narrative, but still the horror of that day comes across strongly. And yes, unfortunately “exemplary violence” is still very much with us today. These days, though, General Dyer would probably be replaced by a drone…