Mahatma Gandhi is one of those people whose position as a hero of history is assured. He overcame the most powerful empire on earth with the power of nonviolence. He is immortalised through his quotable epigrams like “Be the change that you want to see in the world” and “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win” (which he never actually said).

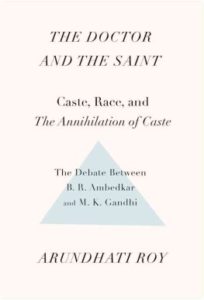

But there’s another side to Gandhi, and it’s revealed in The Doctor and the Saint, Arundhati Roy’s fascinating introduction to a debate between Gandhi and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. This other side involves a defence of the caste system and inequality in India, racism against African people, and several episodes of rank hypocrisy. None of this negates his achievements and his importance to history, but it does allow us to reach a more rounded, realistic view of the man, which seems more useful than uncritical hero-worship.

Gandhi and Ambedkar

First of all, you may be wondering, as I did, who B.R. Ambedkar is and what the debate with Gandhi was about. Ambedkar was an early 20th century intellectual from a Dalit (known in those days as “Untouchable”) caste. Ambedkar wrote a book called Annihilation of Caste in 1936, and Gandhi responded by arguing against Ambedkar and defending the caste system. The edition I read, an ebook published in the UK by Verso Books, doesn’t contain the debate itself—it’s a standalone edition of Roy’s introduction, which is definitely lengthy, detailed and interesting enough to stand as a book by itself.

In case you’re also wondering why a 1936 debate between Gandhi and Ambedkar would be relevant or interesting today, consider these little facts that Roy shares with us:

- Every day, more than four Untouchable women are raped by Touchables.

- A crime is committed against a Dalit by a non-Dalit every 16 minutes.

- Every week, 13 Dalits are murdered and 6 are kidnapped.

- In recent years, some Dalits have been stripped and paraded naked, forced to eat shit, had their land seized, and been prevented from accessing drinking water.

- In 2005, Bant Singh, a Mazhabi Dalit Sikh, had both his arms and a leg chopped off for daring to file a case against the men who gang-raped his daughter.

So the caste system and its attendant evils are still relevant today, just as they were in 1936. (As well as these grim facts, Roy gives plenty more examples in the book.) The basic question of whether some people should have such massive power over the lives of others due to their birth is still very much alive today.

Gandhi and the Caste System

Given what we know about Gandhi and his struggles for social justice, it’s astonishing to see him come out on the side of the caste system in this book. Gandhi believed that the lower castes should be treated well, and he would clearly have condemned the violence described above. But he consistently defended the system itself and the custom of “hereditary occupation”, by which the entire trajectory of your life is determined by the caste you are born into.

In 1921, Gandhi wrote:

“To destroy the caste system and accept the Western European social system means that Hindus must give up the principle of hereditary occupation which is the soul of the caste system. Hereditary occupation is an eternal principle. To change it is to create disorder.”

What comes across strongly in The Doctor and the Saint is Gandhi’s fear of disorder, which Roy links to the generous funding he received from industrialists such as G.D. Birla, who paid Gandhi a substantial monthly retainer from 1915 through to the end of Gandhi’s life to cover the cost of his ashrams and his political work.

Although Gandhi advocated strongly for poor people to be treated better, Roy writes, at no point in his political career did he ever seriously criticise or confront an Indian industrialist or the landed aristocracy. He believed instead in the notion of trusteeship, writing:

“The rich man will be left in possession of his wealth, of which he will use what he reasonably requires for his personal needs and will act as a trustee for there remainder to be used for society. In this argument, honesty on the part of the trustee is assumed.”

It’s a nice idea, but a quick look around the world today will show what became of that assumption. Ambedkar, on the other hand, believed that relaying on the charity of the rich was not enough. He described Hindu society as “a multi-storeyed tower with no staircase and no entrance. Everybody had to die in the storey they were born in.” Ambedkar wanted to tear down this nightmarish tower and build something fairer. Hence the debate.

Gandhi in South Africa

Gandhi’s early years in South Africa are often referred to as his political awakening, but what is not so well known is that he advocated for the rights of Indians at the expense of Africans. For example, he complained against the Durban Post Office having two entrances: one for Blacks and one for Whites. His proposed solution was not to unify the entrances, but to add a third entrance for Indians to spare them the indignity of using the same entrance as the “Kaffirs”.

In an open letter to the National Legislative Assembly, Gandhi argued that both the English and Indians were “sprung from common stock, called the Indo-Aryan,” and he complained:

“The Indian is being dragged down to the position of a raw Kaffir.”

You don’t see that one made into a Facebook meme, do you?

History Rewritten

Much of this history was later rewritten, first by Gandhi himself and then by his many followers and admirers. The result is a skewed vision of a saintly figure, which Roy’s book does much to correct. There are many more examples beyond what I could cover in this post—more examples of Gandhi trying to position Indians above Africans in the colonial hierarchy, of volunteering to aid the British Empire in defeating a Zulu uprising, and later in India of opposing strikes and other protests that seemed to threaten the overall structure of society too much, or of limiting the Dalits’ democratic voice in the constitution of the new independent India.

The point, for me, is not to swing from the extreme of “Gandhi as saint” to a new extreme of “Gandhi as villain.” It’s to reach a deeper understanding of an important historical figure and to reinforce the simple truth that there are no saints and no villains. There are only human beings struggling to do their best while grappling with their own prejudices and external influences. They can achieve great things despite their flaws, and recognising these flaws does not diminish or negate their achievements—it just makes them real. Roy’s excellent introduction to the debate between Gandhi and Ambedkar tells us more about the real Gandhi than the inspirational quote memes clogging the internet.

If you enjoyed this post, please sign up for my free newsletter to stay updated. Or if you want more on Arundhati Roy, read South African writer Lucinda de Leeuw’s excellent guest post on The God of Small Things.

There are 6 comments

Wonderful post and review, Andrew! Ambedkar is a legend in India, but it is sad that he is not more well known internationally. Gandhi’s reputation has taken a beating in the past few years as some of the suppressed facts about him have emerged, mostly because of the internet. They are eye-opening. As you have said, he is a complex, flawed individual. I remember reading in the news that African students got infuriated after reading his comments that they brought down his statue in their university campuses. Glad you liked Roy’s essay / book.

Hi Vishy, Thanks for your comment! I didn’t know that Gandhi’s reputation had taken a hit recently or that people had brought down his statue. Roy’s book was the first I knew of his less saintly aspects. For me, the book didn’t change my admiration for all his achievements, his championing of non-violent protest, his philosophy, etc. It just gave me a more rounded picture of him, which I appreciated. Although I think it’s important to move beyond the “Gandhi as saint” image, I think it would be a shame to go straight from there to “Gandhi as villain”. I’d like to see us celebrating his achievements while remaining aware of his flaws.

Each of us, every one of us, is a prisoner of the times we live in, a prisoner of the times we were raised in, and a hostage of the world view we were educated in, and a prisoner of every single decade of our lives. Gandhi never asked to be a saint or to be called a saint. He didn’t. When you examine the life of any so-called great or good person from the past, you will find that their lives and their thinking DO NOT HOLD UP to today’s thinking. And I must say, Andrew, the older one becomes, the more one understands this.

Hi Judith, I agree with you to some extent. We are all influenced by the times we live in, and it’s easy to look back and judge historical figures harshly by the standards of today.

I take issue with the word “prisoner”, though. To me, that implies that we have no choice or ability to evolve. Human progress has depended on people rising above the prejudices and limitations of their time and helping us all to move forward. Gandhi himself is a great example of this in other areas, like the championing of non-violent protest, which went on to influence so many other resistance movements later on.

I understand that it was a different era, but there were people in Gandhi’s time and for centuries before that who recognised the humanity of African people. And, as the debate with Ambedkar showed, there were plenty who took a much stronger position on the caste system as well. Gandhi deserves to be criticised for his views on race and caste as much as he is rightly praised for all his other achievements.

As I said in the post, I have no desire to demonise Gandhi – I still admire so many things about him. I just have a more rounded picture of him now. To me, that was the value of Roy’s essay.

More discussions like this (Roy’s and your response to her work) could help erode this tendency towards polarized thinking that is so prevalent today. People are complex.

As to whether one generation is always improving upon the generation before, I agree that there have been individuals in every era who have striven towards equality. Just this week I was reading a collection of essays which included a short piece by an American woman writing in the 19thC, Lydia Marie Child, and learned how she had advocated for the rights of African-Americans and been attacked and silenced because of her public stance on the issues.

Yes, she probably got some things “wrong” too, but it’s unfortunate that so many of the people who have tried to work towards equality have been forgotten/overlooked/neglected, leading too many people to think that working towards justice is only a matter of concern for “today”. (Maybe she’s better known in the U.S. but somehow I doubt it.) Maybe for some it’s just too painful to admit how little has changed over the centuries? Maybe for some it’s a rationalization to stop trying or stop hoping in the present-day because their efforts will only be dismissed by future generations?

I hope so! Ideological purity is not a realistic goal even for people today, let alone applied retroactively into the past. We definitely need to get past this binary mode of thinking.

You raise some good points about progress. I’ve never heard of Lydia Marie Child either, but I’d like to learn more based on that quick sketch. I think it’s a real shame when people get overlooked like that. I think there’s also a tendency to focus on a few (often male) “heroes”, obscuring the fact that most social change has come from mass participation by huge numbers of people who did the unglamorous work of organising meetings and signing petitions and turning up to marches, and will never be remembered for it. And many of the things they achieved, like the existence of the weekend, are now so commonplace that we don’t even think about them or acknowledge that people had to fight for them.

I came across a nice phrase recently: “being a good ancestor”. I liked that way of framing our actions, even though I don’t have kids myself. What can I do to be a good ancestor? If I make some positive contributions to the world and help to give future generations a better chance, I’d be happy with that. It keeps the focus on the long game, which is where real progress tends to happen. In the short run, the Trumps of the world tend to be the winners, but in the long run we’ve got a chance of doing better.

Thanks for a thought-provoking comment!