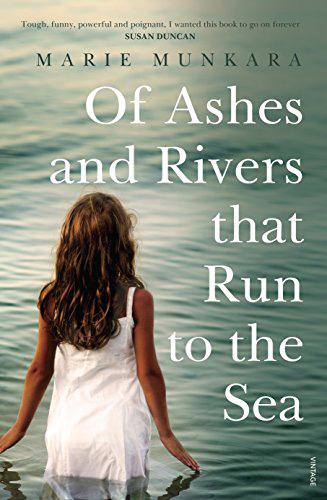

I learnt about Of Ashes and Rivers That Run to the Sea from Emma’s excellent review on Book Around the Corner. It’s a very moving memoir by a woman, Marie Munkara, who was taken from her Aboriginal family in northern Australia at the age of 3 and placed with a white foster family in Melbourne.

The Stolen Generations

Munkara was one of thousands of members of the “Stolen Generations” of Aboriginal children taken from their homes by the Australian government or church missions. According to Wikipedia: “Official government estimates are that in certain regions between one in ten and one in three indigenous Australian children were forcibly taken from their families and communities between 1910 and 1970.”

This brutal policy was so common, especially with lighter-skinned children who could be more easily assimilated into White Australia, that Munkara’s family considered throwing her to the crocodiles at birth:

It was better that we die in our own piece of country than be taken by the authorities and lost to our families forever.

From Loving Family to Child Abuse

Although the rhetoric around this state-sponsored child trafficking was about giving kids a better chance in life, it doesn’t work out that way for Marie Munkara. Her foster mother is cold, critical and angry, and her new father is a paedophile who abuses her regularly throughout her childhood. She knows nothing about her true origins until, at the age of 28, she discovers her baptismal card slipped inside a book and begins to track down her Aboriginal family in a small township on Bathurst Island on the other side of Australia.

It’s not an easy reunion, however. Think about all the things that happened to you between the ages of 3 and 28, and how they shaped your beliefs, your personality, and more or less everything else about you. Marie Munkara was shaped by the values of her racist parents (before she goes to Bathurst Island, her foster mother warns her that they’ll take all her money: “You know black people are shifty and dishonest, I’ve always told you that”). She is initially disdainful of her family and how they live, distrustful of the Aboriginal people she meets, and wary of large crowds of “blackfellas”.

Culture Shock

What follows, then, is a profound experience of culture shock. Munkara is appalled by what she sees as the lack of hygiene, disregard for her possessions, cruelty to animals, and more. She tries to tag along on hunting or fishing trips and gamely tramps through mangrove swamps looking for mud crabs, but she is always the outsider, never able to understand or to keep up or to do the things that come naturally to them—and would have come naturally to her, too, if she hadn’t been taken away.

After a lifetime of not being white enough for her white family, then, she quickly discovers that she is not black enough for her black family. She sums it all up towards the end of the book:

I know that I’ve disappointed them all. The anger from the white parents. The pitiful looks from the black. The fretful and all-consuming silences from them both. I wish I could open the doors to my mind and let them in, so they could see the world from my eyes and forgive me for not being able to fit their expectations. But I can’t because this journey is all mine.

Alternative Pasts and Futures

Although Munkara does become close to her Bathurst Island family in the end, it’s a profoundly difficult process. I can’t help imagining what her life would have been like, and by extension what the lives of thousands of other Aboriginal kids would have been like, if this profoundly racist policy had never been enacted. Marie Munkara would probably have missed out on some of the material and educational advances, but she would also have escaped the emotional and physical abuse, as well as the dislocation and alienation.

It’s impossible to know what would have happened, of course, and as tempting as it is to wonder, it makes no real sense. It happened, and those other possible futures are gone. Marie Munkara is who she is. As she says of her two families:

They don’t realise that there is no stolen and there is no lost, there is no black and there is no white. There is just me. And I am perfect the way I am.

But still, I wonder, and I seethe at the injustice of it all. I’d read about the Stolen Generations before, but reading this personal story really brought the horror and complexities of it home to me in a new way. At a time when open racism is becoming part of mainstream political discourse once again in some parts of the world, I’d recommend Of Ashes and Rivers That Run to the Sea as a powerful antidote.

Read more posts about Australian literature. Or sign up for my free monthly newsletter. And please comment below to let me know your thoughts!

There are 8 comments

Great review Andrew. It gives a good vision of the book and the issues Marie Munkara shares. It must have been a very difficult journey for her. The culture shock was violent, wasn’t it?

There’s a lot more about Aboriginal lit and non-fiction on Lisa’s blog. (ANZ Litlovers) I have read True Country by Kim Scott and I recommend it.

Thanks for the link to my billet.

Thanks Emma! Yes, the culture shock was very violent. I admired how the writer didn’t try to hide or soften her own initial prejudices or the characteristics of her family that might make them look bad to outsiders. It felt like a very honest book. And I also like how she communicated the culture shock with a heavy dose of humour. Despite the sadness and the tough themes, it was a fun book to read, and I think that’s quite an achievement.

Yes, ANZ Litlovers is great! I have fallen behind with reading blogs (along with writing my own!) but am planning to devote more time to it again, because I always enjoyed it. I plan to join Indigenous Literature Week next year as well (and maybe I’ll read that Kim Scott book—thanks for the recommendation).

Excellent review Andrew. I love how you’ve distilled the essence of her experience.

I’ve read and reviewed a book that captured many of the stolen generations stories. What comes out is that many were abused in one way or another – some sexually, some physically and/or some emotionally (taken advantage of, treated as servants etc.) Some though were treated well, and love the foster parents who treated them well but they mourn the loss of their culture, the inability to ever, really, properly engage with their family and culture. That is an irrevocable loss, I think.

Thanks very much! This was my first book dealing with issue of the Stolen Generations—I’d only read about it before in articles. It’s astonishing to me that people could abuse children in the name of religion and civilisation, but I suppose it shouldn’t surprise me at this point. You make a very good point, though—even if the children were treated well, it would still have been a huge loss.

Is the book you’re referring to the one edited by Carmel Bird? Just read your review of it, and it sounds very good. Am linking to it here for people who want to learn more: https://whisperinggums.com/2017/10/26/carmel-bird-ed-the-stolen-children-their-stories-bookreview/.

Great review Andrew. What went on with the stolen generation was the Indeed infuriating and disturbing. What these parents and children went through was unimaginable.

Ms. Munkara’s experiences seem fascinating. I think some folks would have given up trying to intergrate back.

The book sounds so good. I may give it a try.

Yes, it’s quite shocking to read about, Brian. The book is also quite entertaining, which didn’t really come across in my review. She’s a great storyteller.

I know you’re reading more of the classics these days (or at least that’s what you’re writing about!), but if you feel like something contemporary, I’d recommend this one.

This is a book my book club would adore! The more horrifying the better, I’m not sure if that is good or not… but this sounds truly heartbreaking!

Hi Dani

Thanks for stopping by! I think it would be a good book club read, actually. It’s definitely a heartbreaking story, but it’s also told with a lot of humour and insight. I think my review focused more on the horrifying aspects, but there’s more to it, and plenty for a book club to discuss.