Authors and publishers generally live in different camps. They have their own associations, their own awards, their own complaints about the people in the other camp. Meike Ziervogel is one of the few people to have a foot in both. She’s the founder of Peirene Press, which publishes contemporary European fiction in translation, and she’s also written two novellas, published by Salt Publishing.

Authors and publishers generally live in different camps. They have their own associations, their own awards, their own complaints about the people in the other camp. Meike Ziervogel is one of the few people to have a foot in both. She’s the founder of Peirene Press, which publishes contemporary European fiction in translation, and she’s also written two novellas, published by Salt Publishing.

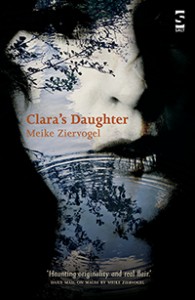

The first, Magda, explored complex mother-daughter relationships through the harrowing story of Magda Goebbels and her poisoning of her children. The second, Clara’s Daughter, which came out this month, is billed as a mother-daughter story too, and the title primes you to read it that way, but to me it was about a lot more besides.

The main character, Michele, seems to have everything she wants: a family, a high-powered job, a nice house in Hampstead. But it all seems strangely hollow, and the things that should make her happy are sources of strain. It’s clear that she loves her husband, and her mother, and her sister, and her job, but they’re all dragging her in different directions. Whether it’s her husband wanting intimacy or her mother needing care, she never seems to have the time. Her kids, meanwhile, are gone, only appearing in the book obliquely, through a look at their empty rooms and a photo on an iPhone.

It’s not surprising, then, that some of these loved ones start to feel more like encumbrances, and gradually remove themselves from Michele’s life. First to go is her husband Jim, walking out into the rain one night after an argument about things like whether to light the candles and where to put the clay model Michele’s mother gave her.

The scene is typical of the book: quiet, understated, yet packing a heavy punch. The argument is obviously about much more than a clay model and some candles, but these things are never mentioned openly. Only Jim’s abrupt suggestion to make love in the rain and Michele’s dismissive reply show the distance between them, but you can feel it all through the arguments over minutiae. When he walks out, it feels like the only logical thing to do.

Michele’s mother, Clara, moves into the basement, but quickly feels unwanted, and begins to plan a way out.

I felt safe in my own house. Here I don’t feel safe. The walls are too white. Like in a madhouse. Michele never liked me. I know. […] They have put me in a cellar. Out of sight, out of mind. I won’t have it.

But freedom is not what Michele wants. As she begins to lose more and more elements of her life, she doesn’t seem to feel any lighter. The attachment she feels for them never wanes—in fact, it seems to strengthen. She thinks about Jim, imagines the two of them in happier times, and struggles to let go of the bin bags containing his clothes. Unencumbered, she feels lonely and consoles herself by buying towels online. She wants it all, it seems, even though it’s more than she can handle. It sets up a fascinating conflict, and a satisfying conclusion.

The structure of the book is also interesting. It’s a very fragmented narrative, starting with a scene of marital bliss that turns sour, then jumping forward a week to a scene of Clara bagging up Jim’s clothes after he’s slept with another woman, and then jumping back and forth to fill in what happened in-between, as well as going forward up to 18 months in the future to see how Michele deals with the aftermath. Sometimes we find ourselves in a scene that seems incongruous, only to discover that it’s a memory.

This choppy narrative can be a little disorienting, but it serves a purpose. It misleads us in the same way that the characters are misled. We see something from one angle, only for later (chronologically earlier) events to show us that the truth is quite different. Much of the plot development is a result of misunderstandings that, thanks to the structure, we share with the characters. As it goes on, we discover more about what really happened, and how Michele and Jim and Clara had things wrong, and how things could have been different. Or maybe they couldn’t. Maybe they’d have ended up in the same place, even if by a different route.

On my first reading, I felt as if there was too much of Jim in the book and not enough of the mother-daughter relationship. But I think that was just because of the expectations set up by the title and the cover blurb. In fact, Clara’s Daughter is richer for not being merely a story about a daughter, but also a story about a wife, a mother, a CEO, and a human being who wants things she doesn’t know how to have.

The book follows the Peirene formula: short (131 pages, with some pretty generous white space) and yet offering the reader plenty to chew on. The story is told in spare, simple prose for the most part, never trying too hard, and yet achieving a lot. It’s a cleverly drawn, intricately plotted portrait of a family in which people are forced apart not because they don’t love each other, but because of their inability to articulate that love and act on it. Thought-provoking stuff.

There are 9 comments

I had not heard about Clara’s Daughter before. I’m glad I read your review. I can appreciate your initial hesitance about the narrative structure. Sometimes it can feel gimmicky or simply confusing. I don’t mind being challenged as a reader, but my patience can wear thin if I’m pulled out of the story too often trying to find the plot line. But it sounds like the narrative works well in this novel. Kudos to this author for trying this experimental structure and making it work.

Great review.

Hi Jackie,

Yes, I think for me it depends on whether I can see the purpose in the structure. Sometimes it feels as if writers just had a normal story to tell, and tried to make it seem more “literary” by messing around with the sequencing. That isn’t the case here: there’s a clear justification for the structure, and it’s really well tied in with the plot and with the themes of the book. Thanks for commenting!

I like the sound of it and your review does justice to the book, it makes me want to read it.

I don’t read translations in English but Pereine does a great job, according to the English-speaking bloggosphere.

Thanks Emma! Yes, Peirene produces some good books – I’m never sure how to judge the quality of translations without having read the original, but they read well in English anyway 🙂

I think this might be the most compelling review of Clara’s Daughter I’ve read yet (I’ve seen good reviews all over the blogging world recently). I think after loving Magda as much as I did this is worth a try. I do love a short novel you can get lost in for a few hours.

Thanks Alice! I appreciate that. Yes, I think you’d enjoy this one. It’s quite different from Magda in some ways – a much quieter kind of story. But definitely worth reading, and yes, you can get lost in it!

I’ve read Annabel’s review of this and now yours, and I am beginning to think I must read this! Those very French novels with lots of white space and complex chronology tend to remind me of my university research! So I’ve often avoided them as I switch into work mode with them. But this does sound intriguing.

Ah, I can see your dilemma 🙂 Switching into work mode is not a good thing. I haven’t seen Annabel’s review – will go and have a look at that.

I think my favourite aspect was the structure; I like how you’ve linked the misunderstandings with the reader, that’s very true. It made so much more of what was there.