My thoughts on Mikhail Bulgakov’s long-banned satire on Soviet social engineering.

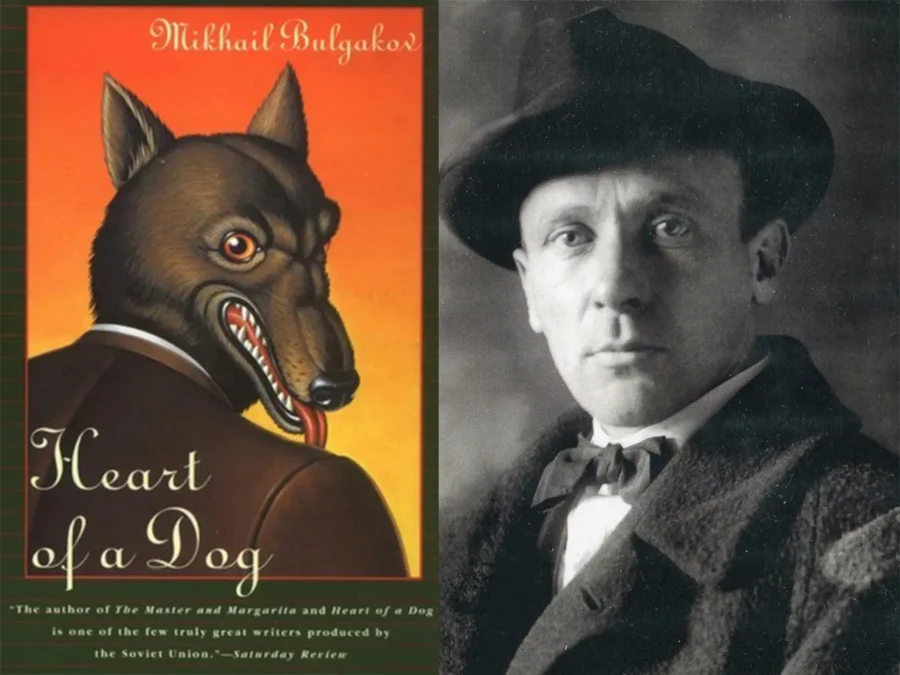

What would happen if a pioneering surgeon transplanted organs from a recently deceased criminal into a stray dog? When the idea is filtered through the imagination of Mikhail Bulgakov, the result is a sharp satire of Soviet attempts at social engineering.

The Heart of a Dog is a fairly short novel, probably closer to novella length, and a much easier introduction to Bulgakov than his major work, The Master and Margarita. Like that novel, this one has plenty of absurd and comedic elements, with strong political undertones.

It’s chastening to think that while many of us today are reticent to speak out on certain issues for fear of backlash, Bulgakov wrote this searing critique of Bolshevism and submitted it for publication in 1925, when the USSR was under the rule of Joseph Stalin. So, although I’m reading it for two 1925-themed book-blogging events (The 1925 Club and Hundred Years Hence), this book’s publication history is more complicated. For decades, The Heart of a Dog was available only via dissident samizdat, and it remained banned from official publication until long after the author’s death.

The political implications are much more open than in The Master and Margarita. There’s the main story, of course, which is obviously poking fun at Soviet attempts to change human nature and engineer a “New Soviet Man.” The results are comical: the stray dog, Sharik, quickly morphs into a nightmare of a man, Poligraf Poligrafovich Sharikov, who has an inflated sense of entitlement and a dim sense of morality, and who engages in political chicanery with the housing committee while also howling and chasing cats.

Despite the novel’s title, Sharikov’s creator, Dr. Preobrazhensky, explains that it’s the human elements, not the canine ones, that are the problem. In one place, he regrets his operation to “transform a most likeable dog into such a nasty piece of work it makes the hair stand on end.” And later, he says to his assistant:

“You have to realize that the whole horror of the thing is that he already has not the heart of a dog but the heart of a man.”

The disastrous results of the operation are a clear commentary on the USSR’s aims of uplifting the proletariat. And other critiques of Bolshevism are also woven through the novel.

The housing committee, which is appropriating the apartments in Dr. Preobrazhensky’s building and breaking them up into smaller accommodation, is a frequent target for mockery. Its members are pedantic and vindictive, and yet they fail to take any of Dr. Preobrazhensky’s ample space because he counts senior government officials among his patients and is able to call on them for favours.

Later, as Sharikov gets his official papers and finds a job as a cat-catcher, we see a system riddled with corruption and favouritism, governed not by its high ideals but by connections and power. Dr. Preobrazhensky several times expresses his contempt for the proletariat who are stealing his galoshes, as well as his dislike of the system in general. While the author’s views don’t necessarily align with the character’s, the criticisms expressed in The Heart of a Dog are quite explicit, and I can see why Stalin wouldn’t have been a fan.

The book doesn’t have the depth and complexity of The Master and Margarita, which is to be expected of a novella with a simple satirical premise. So I’d recommend the other book to see the best of Bulgakov, but The Heart of a Dog also has plenty to appreciate and is a quicker, easier entry point.

Have you read this or any other Bulgakov novels? Are you taking part in either of the 1925 reading events? Let me know in the comments.

There are 11 comments

I love this book – but then I love all Bulgakov. M&M is always going to be the favourite, but I think both this and Fatal Eggs are wonderful short satirical novels (novellas?) which really capture their era and also take the rise out of them! I had considered going back to one of Bulgakov’s titles for 1925 but haven’t got to it – maybe I’ll do so for Novellas in November. Thanks for taking part in the Club.

You’re right, it does capture the era really well. I just looked up your review from back in 2013 and would recommend it to anyone who sees this and is looking for another opinion: https://kaggsysbookishramblings.wordpress.com/2013/02/14/an-old-favourite-a-dogs-heart-by-mikhail-bulgakov/

I’ve not read Bulgakov though I keep meaning to “one of these days.” You know how it goes. This one sounds like an interesting read, though I suspect when/if the one of these days arrives I will go right to M & M 😀

Oh, I do know how it goes – I’ve got loads of those “one of these days” books and authors on my TBR list. Hope you get to Bulgakov one of these days. By the way, there’s a pizza place here in Serbia called The Master and Margarita. Gotta love a literary fast food pun 🙂

Great review! I have enjoyed it as well, and also The Master and Margarita, though as you said the satire is much more coded in the latter

Thanks Emma! Glad you liked this one. Our reading seems to overlap quite a bit!

Indeed!

He really had guts to criticise the establishment under Stalin! I have M&M on my shelves but it daunts me. This seems an easier read. I shall search for it.

Thank you for taking part in #HYH25. I shall link this up.

Yes, I was quite amazed at how clear the criticism is here. It was right at the beginning of Stalin’s rule, so probably he didn’t have as tight a grip as he did later on, but still, it did take guts to write this.

Thanks for organising this event! Hope you like this book if you do end up reading it.

What a timely read! (Unfortunately. I’m sure MB was hoping he would be out of fashion by now.) I would like to make a point of reading through his work (and other courageous Russian writers who turned to fiction to express their hope and desire for change) but didn’t even think of this one for 1925.

I think that would be a wonderful project! There’s a lot to learn from writers like Bulgakov as we start to navigate treacherous political waters of our own.