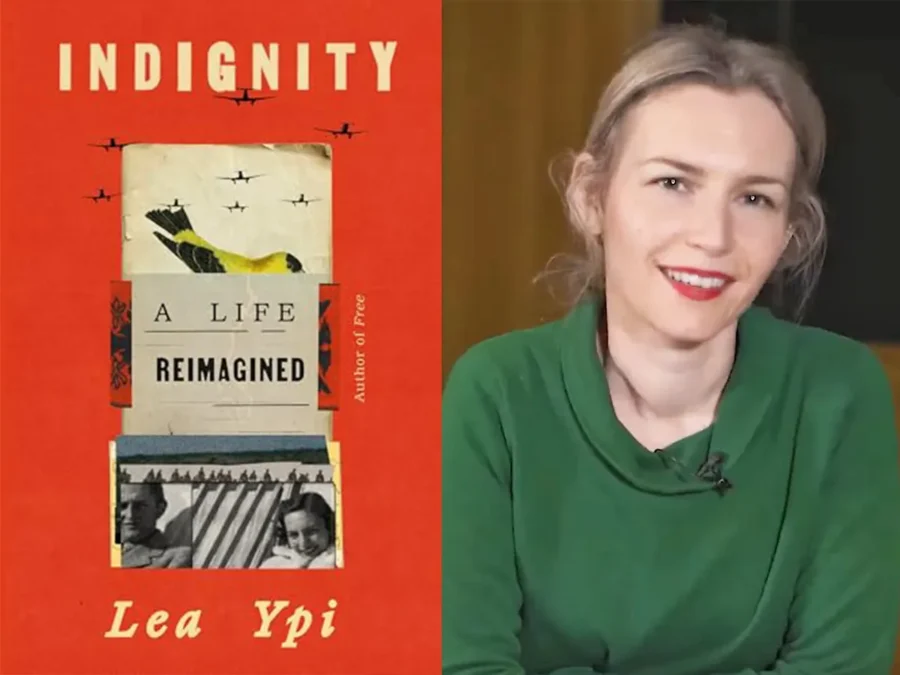

This book started with a social media post. The author, Lea Ypi, saw a photo of her grandmother posted online and going viral in Albania. Some of the comments were offensive and wildly inaccurate, and since her grandmother is now dead, she could not respond. The sight of strangers casually shaping and summarising her grandmother’s life made Ypi want to set the record straight and tell the truth.

But what is the truth of a life? Ypi knew some of it from her own experience of her grandmother and the conversations they had, but there were still large gaps. The photograph raises questions for her too: it’s from 1941, when her grandparents were honeymooning in the Alps, a time her grandmother always described as the happiest in her life. But how could she be happy amid the horrors of World War II?

Ypi being an academic, she heads to the archives to find answers. As you’ve probably guessed from the fact that an old 1940s holiday snap went viral, Ypi is from a prominent Albanian family. Her paternal great grandfather was Albanian head of state on two occasions, and her maternal great great grandfather was a pasha in the Ottoman Empire. So the archives hold more information on her family than they would on others. Yet there are still huge gaps and unanswered questions, which is a major theme of the book.

Although the title of the book is Indignity, the book is more about its opposite. Its genesis was Lea Ypi’s attempt to defend her grandmother’s dignity, but it also goes more broadly into the idea of recovering the dignity of individual human life in political climates that attempt to destroy the individual.

For, although Ypi’s grandmother Leman came from a prominent family and married into an even more prominent one, her life was seriously affected by the volatile political times she lived through, encompassing the demise of the Ottoman Empire, the authoritarian rule of King Zog in Albania, Nazi occupation in World War II, and then the authoritarian rule of Enver Hoxha’s Communist regime after the war.

The other characters in Indignity also suffer at the hands of what you could call fate or wider social forces or just the outside world. Her family suffers a downturn in fortunes as Ottoman Salonica became Greek Thessaloniki, her childhood maid Dafne is forced to move to Turkey as part of the population exchange, her aunt Selma is forced to marry a rich German businessman, her cousin Cocotte is badly burned in the great city fire, the family doctor fights in vain to preserve the Jewish cemetery and then is persecuted by the Nazis, etc.

In the later parts of the book describing the Hoxha regime, Leman and her husband Asllan are both seen as politically suspect, with Leman being sent to work on a collective farm and Asllan being imprisoned for 20 years.

The characters featured in Indignity have widely differing responses to the circumstances they find themselves in. Yet, amid all of it, the human spirit shines through.

“There is something about the human spirit, my grandmother would say, that withstands all attempts at offence, injury or humiliation—something animals are incapable of, because they are incapable of thoughts disconnected from their immediate existence. We call it dignity.”

The word “Reimagined” in the title is important. The archives can only take Ypi so far: they provide some details, particularly in the records of the former Albanian security services, which include extensive details of who Leman spoke to, what she said, where she went, etc. But to tell the full story of her grandmother’s life, she needs to imagine some of it.

So what we get is a kind of hybrid of memoir and historical fiction. Ypi’s present-day encounters with social media trolls and archivists are the framing device for each section, and there are also occasional “Intermezzos” in which documents from the archives are reproduced verbatim. But the majority of the book is a fictional tale of Leman’s life, from her childhood in Salonica to her young adult life in Tirana, her romance and eventual marriage, the war, and then life under Hoxha.

It’s interesting, however, that this is not “A Life Imagined” but “A Life Reimagined“. Imagination seems more appropriate for the activity of a historical novelist, but Ypi has clearly chosen the word “Reimagined” for a reason.

There are perhaps two reasons. One could be related to the social media storm that prompted the book: those strangers took the liberty of imagining Leman’s life, and now Lea Ypi is responding with her own act of reimagination. The second reason is connected to a twist at the end of the book, which I won’t give away here, except to say that it raises questions about the accuracy of the archives and whose life is being documented. It leads Ypi to revise much of what she thought she knew, and perhaps that’s the act of reimagination.

So there are lots of interesting themes to chew on in Indignity. It was the best book I read in September, although that was a low bar, as I mentioned at the time. The strengths of the book are what I’ve described so far: its assertion of human dignity and depiction of how individuals survive and navigate turbulent political times.

And yet I didn’t love the book as much as I expected to. I think it’s because of the hybrid form which, although interesting, didn’t quite work for me. The fictional sections, which make up most of the book, are well written but don’t work as a novel. There’s no narrative arc or anything like that. It’s just the narration of a life: an interesting life, lived in interesting times, but still not exactly a story.

Because the aim is to tell us the truth of Leman’s life, while also including a depiction of the complicated political background and switching back to the non-fiction parts about the author, we end up covering a lot of ground, and it feels rushed in places as we skip forward through different eras. The later sections about life under Communism feel especially scanty, with more focus on the author’s archival work and speculation about who the informers were, and less on things like how Leman coped with the loss of her husband for so many years in prison, what perspective she gained with age, how she experienced the post-Communist era, etc.

I think Indignity could have worked better as a historical novel, with the author’s archival research in a prologue and/or epilogue. But this is the book Ypi wanted to write, and perhaps making it a novel would have taken her away from her original goal of telling the truth of Leman’s life and involved a little too much reimagining.

I still think the book is well worth reading, despite the reservations I mentioned towards the end. It gives a real insight into life in the Balkans in the first half of the twentieth century and how individual people lived their lives and asserted their dignity in different ways amid the political turbulence around them.

There are 6 comments

Sounds interesting and I understand why the author felt like they needed to combine fiction with nonfiction, but it also sounds like it wasn’t a very seamless combination, which is unfortunate. I wonder if the boo reached any of the people that had posted online and whether it changed their stories about Leman?

I hope it did reach them! People often post their thoughts online without thinking about the real human beings on the other side of the screen. I think it would be good for them to reassess their opinions, if they’re open to that.

Even given your caveats about the form and the author’s approach, this does seem like a fascinating read. I love this kind of book that delves into big political issues, viewing them through a very personal lens. It reminds me a little of Marta Barone’s Sunken City, in which the author tries to reconstruct a picture of her father’s life, including various acts of resistance during Italy’s Years of Lead.

Thanks for writing about this one as I may well try it on audio, which I often use for non-fiction and hybrid works.

I don’t know that book, but from reading your review, it does seem quite similar. I normally love this kind of book too, so I was surprised not to feel more strongly about Indignity. Despite the caveats, I do think it’s worth a read, especially if you’re into books like this.

it sounds like one of those instances where the story behind the story is almost as interesting as the story itself. Also one of those instances where, if one’s interested in matters of craft, the question of how to handle the ideas of facts and truths is almost as interesting as the story itself too. This whole question of hybrid forms sends me spiralling, in a good way. Although it alllllllmost seems like too much to not only play with the non-fiction/fiction question but also introduce the question of how we view (and re-vision) history right in there too. How much fun is it to spiral, before it turns into “well, now I’m simply dizzy”.

Yes! I should have mentioned that the author is a philosopher, so I think it’s her job to make us dizzy 😉