Why was I disappointed by a novel that everyone else seems to love? Follow me as I try to find the answers.

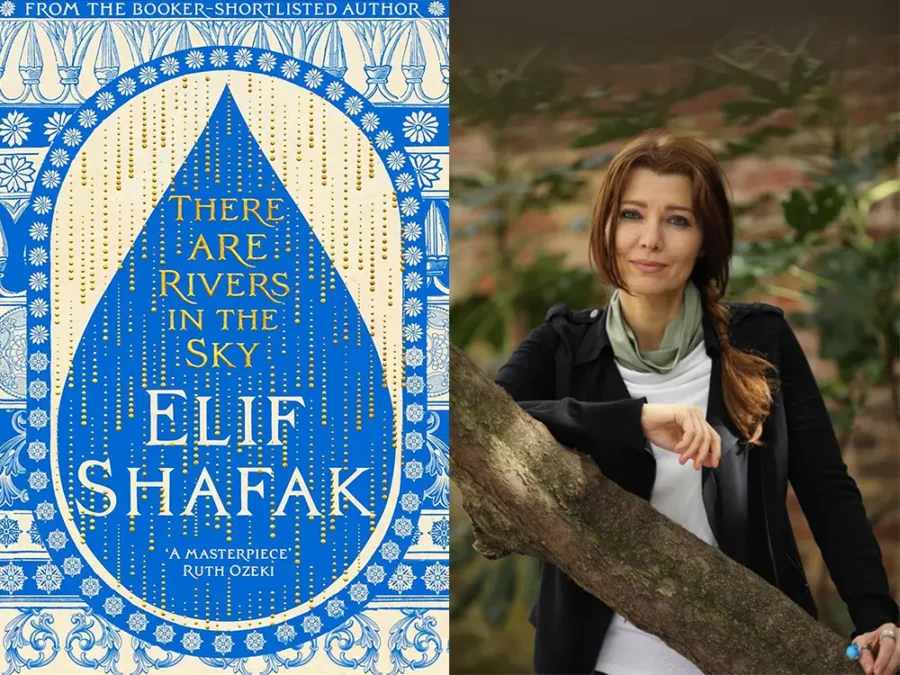

Maybe I’m wrong about this one. I mean, Ruth Ozeki calls it an odyssey, an epic, a lament, a clarion call and a masterpiece, all in one short blurb. Mary Beard calls it a “brilliant, unforgettable novel”, while Nadifa Mohamed calls it “Literature on a grand scale.” Critics, novelists and Goodreads reviewers all seem to be competing over how much praise they can heap on There Are Rivers in the Sky, the new novel by Elif Shafak published in August.

So why did it leave me cold? After all, I’ve read and enjoyed many of Shafak’s previous novels. I listed 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World as one of my best books of 2019. And I love the concept of a historical epic with the characters all linked across space and time by their interaction with a single drop of water.

There are also some beautiful and poignant moments throughout the book, especially in the sections involving Narin, a young Yazidi girl living a peaceful life with her grandmother by the banks of the Tigris until they encounter the brutality of ISIS. Shafak’s writing is never bad, and I certainly didn’t hate this book. But I didn’t agree with any of the quotes and reviews. It was admirable in many ways but ultimately disappointing for me.

I think there are several reasons for this: one structural, one conceptual, and one to do with character.

1. Disconnected Narratives

The first is that the strands are too disparate. We start with King Ashurbanipal in ancient Nineveh, and then we skip forward to Arthur, a baby being born in the Victorian slums of 1840s London, and then we spend some time with Narin in 2014 before skipping ahead to Zaleekah, a depressed academic living on a London houseboat in 2018. The king is quickly abandoned, and most of the novel involves switching between the other three narratives.

All the characters are connected by that drop of water as it completes its long cycle of falling as rain, flowing out to sea, etc. It’s a beautiful image showing the unseen connections across time and space, but it’s quite tenuous as a way of linking narratives. They’re also brought together in the denouement, but it didn’t feel particularly satisfying to me and wasn’t enough to justify almost 500 pages of entirely separate stories.

2. Undercooked Characters

The second problem is in the characters themselves. Arthur gets the most airtime of the three, and although on the surface it was a compelling story of rising from poverty to become an expert on Mesopotamian artefacts and to uncover the mysteries of the Epic of Gilgamesh, I struggled to maintain much interest. It felt more like a biography of a historical figure than a story about a human being.

That was very surprising to me because one of the strengths of Shafak’s writing in the past has been her ability to create characters who feel utterly real and compelling. That wasn’t the case for me with Arthur Smyth. Maybe it’s because we skim through his whole life at high speed, never lingering long enough on interesting details. For example, Arthur has a perfect memory—he never forgets anything, and he can recall not just details and conversations from years ago but even the snowdrop that fell on him as he was born in the mud and filth on the banks of the Thames. This could have been explored in very interesting ways, as Jorge Luis Borges did in his short story “Funes the Memorious”, in which the teeming particulars that crowded a man with a perfect memory made it impossible for him to generalise. But in There Are Rivers in the Sky, it mostly just functioned to make Arthur more of a genius and less of a believable character.

Zaleekah was potentially interesting because she was so clearly lost and as a reader you want to know why, but she spent most of the novel in denial about the problems besetting her, and we spent so little time with her that her epiphany, when it came, felt underwhelming.

As for Narin, it was fascinating to get a glimpse of Yazidi culture, which I encountered a little in my travels in Armenia and Georgia and was happy to see rendered so well in fiction. Hers is the most interesting narrative, which is strange since she’s just an innocent nine-year-old kid. The other two characters should have offered more complexity, but the opportunities were missed.

3. Research Overwhelm

The third problem is, I think, related to the other two. There was clearly an enormous amount of research involved in creating There Are Rivers in the Sky, and it shows. What I mean is that in trying to convey the wealth of research she uncovered, I think Shafak undercooked the most important things in a novel: character and plot. At times, she just has the characters convey chunks of research to us in their conversations, and at others, they offer opinions on things like the theft of artefacts for European museum collections—opinions I generally agreed with but didn’t need to have spelled out for me like that.

Ultimately, I think perhaps the concept of the novel contained its flaws for me (and perhaps also what other people loved about it). Water is perhaps the antithesis of a fictional character: it flows and shapes the world around it but has no desires, no goals, no hopes and fears. The attempts to make raindrops and rivers into characters fell flat for me, and the water-based structure felt too amorphous, too difficult to grasp. Yet these are perhaps the very qualities that all those other readers loved.

So take my thoughts on There are Rivers in the Sky with a large pinch of salt, check out other reviews, and by all means give this one a try. I’ve focused more on the negatives here because I was trying to understand why my reaction differed so wildly from almost everyone else’s, but the novel does have plenty of good features too. You can do a lot worse than reading it, but you can also do a lot better—pretty much anything from Shafak’s back catalogue is better than this. I’d recommend Honour, The Island of Missing Trees, and 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World in particular.

There are 51 comments

What a bummer the book didn’t really work for you. It’s always extra disappointing when you’ve read and liked other books by the author. I have this one in my TBR pile on my desk and hope to get to it in the coming months. It’s a big pile though, so you never know 😀

Hey Stefanie, this comment makes me very happy. Elif Shafak’s book may not have worked for me, but I’ve FINALLY succeeded in getting comments working again on my site!! Thanks for letting me know about the problem and for persevering in leaving a comment despite all the issues recently 🙂

And on the bright side for you, There Are Rivers in the Sky does have a beautiful cover design, so it will make an aesthetically pleasing addition to your TBR pile.

Well we’ll see what happens when I finally get around to the book 🙂

So glad you got your comments working again!

I really appreciated reading your review – I had a similar reaction to this book: it truly disappointed me, particularly after all of the high praise.

I’m hosting an upcoming book group and “Rivers” is the book that we voted on reading, based on one member’s statement that it is “outstanding” and sure to be loved by all. When we meet as a group, I will likely (and, to me, inexplicably) be the lone dissenter in terms of loving the book, so it’s rather heartening to see that my opinions are shared by someone out there. 🙂

Hi Tammy, Glad it was helpful. I had similar feelings after reading the book and seeing all the gushing reviews out there. But the comments on this post suggest that we are not alone!

Thanks for this full and thoughtful review Andrew. I quite enjoyed 10 Minutes but was not bowled over, so will probably not go for this one.

Hi Mandy, good to hear from you! I don’t generally write negative reviews, but sometimes I find it useful to try to work out why a particular book didn’t do what I thought it should. Glad it was helpful for you too.

I know what you mean, that sense of “what did I miss” when not only are the blurbs and interviews and supporting materials all positive but one has personal experience with the author’s work that’s positive too. Sometimes I think it’s just timing. But I can also recall many instances of that burdensome-expertise that has saturated novels that I otherwise loved (even when I found the research itself fascinating). It’s hard to edit out parts of reviews that are interesting but weigh things down and detract from the overall piece (when one has a word limit, I mean, not just casually bookchatting), so I can only imagine how much harder it could be to delete entire sections of research that really resonated for the author but might not actually fit in the finished manuscript. Did it put you off so badly that you’d hesitate to read another? (I’ve read The Bastard of Istanbul and one other, also very early.)

Yes, it must be hard to delete research that’s fascinating but not quite relevant. I think it infected the characters too—Arthur Smyth is apparently based on a real historical figure, so perhaps that’s why his sections came across to me more like a biography than a compelling human story.

I think I probably will read more Shafak books, but I’ll probably go backwards rather than forwards. I’m very interested in The Bastard of Istanbul, for instance, but I won’t be rushing to try her next one.

Elif Shafak always receives heaps, tons of praise, no matter what book of hers is in question, so I am not at all surprised. That’s her bubble and publishing influence. Sure, I also consider 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World “good”, but that’s where I stopped in 2019. She puts out a book a year, this is to be expected. “Disconnected narratives” and “undercooked characters” – I find it true re a number of her books, though you do recommend Honour, and I haven’t read that one, and am now intrigued. Thanks for this review. I do appreciate your honesty, and think that critical reviews are essential for readers to make good judgements and think critically.

Hi Diana, Yes, I think the publishing industry tends to work like that. Shafak has been shortlisted quite a lot for her recent books, so the assumption is that she’s due a win, and people don’t want to look stupid by panning a future Booker winner. And there’s a lot of mutual back-scratching going on in the blurb-writing business, I’m sure.

I do think Shafak deserved the attention in the first place for her earlier work, though, and would definitely recommend Honour. I’m also intrigued by The Bastard of Istanbul and may try that one next—maybe this is a case where reading backwards through her catalogue would be more rewarding.

I’m so glad I found your review, because I completely agree with it. I just let the book go last night, after about 70 pages, and I feel relieved. I actually found the writing to be trite. I also hate when a writer spells everything out for the reader. It’s my first book of hers, and was sucked in by the blurbs, esp Mary Beard! I think these writers must be friends and give each other nice blurbs. Too much purple prose and corny dialogue. I was really disappointed. My standards for literature are high, though, I admit.

Hi Gail, Thanks for stopping by. Good for you on two counts: first for having high standards for literature, and second for letting go of a book that’s not working for you. I tend to soldier on to the end, and it rarely pays off when things have got off to a bad start.

Sorry that this was your first Shafak. If you ever want to try another of hers, I can recommend earlier books like Honour. But I get the impression you probably won’t, and I can understand why. Better luck next time!

I’m glad to see that someone else felt as I did. The New York Times review was gushingly positive (The Guardian review was spot on) and I felt so flummoxed by that. I am a writing teacher of high school seniors and I swear I could’ve picked out so many sentences that I would ask them to rewrite. So much telling, so little showing, way too much was unbelievable in its connections; overall not convincing. Like others there were parts I liked, especially learning of the Yazidi culture and the genocide with ISIL, which I’m embarrassed to say I did not know about. I love Gilgamesh, and I love learning about Mesopotamia. But in terms of writing quality, this book was quite weak.

Hi Bean, Thanks for stopping by. I hadn’t seen that Guardian review, but you’re right, he hits on a lot of the flaws that I was trying to identify in my post. I think writers get to a point of fame where editors either don’t dare ask them to rewrite things or don’t care because they know the book will sell anyway. But this book could really have benefited from serious editing to bring out all those good elements and iron out the flaws.

Hi Andrew. We share (me by marriage) a last name. I also share most of your views on this book. Perhaps it was obvious, but I wanted more closure with the ending, specifically with how Leila connected Arthur with Narin.

Overall, the metaphor of water was at once tenuous, as you refer to with the raindrop, and overdrawn, with the rivers. But I’ve been a grumpy reader of late, finding metaphors overused.

Hi Joan, pleased to meet you. I used to think it was a rare name, but the internet has revealed that there are quite a few of us out there!

I enjoy a good metaphor, but I did feel that the poor raindrop was asked to do a bit too much work in this novel. I do like the concept, and perhaps if it had been a bit more in the background and the connections between the characters and plotlines had been stronger, it would have worked better.

Hi Andrew,

I didn’t realize you’re a fiction writer and a reviewer. Your list of reads intrigues me–I have not read many of them, but I’ll put them on my list. I did read Our Missing Hearts, and I absolutely agree with you on that one, too. Which of your books should I read first?

I’m a writing teacher (30+ years), but it’s time for me to peace out in our current AI world. Though most of my students remain authentic and truly want to write their own words and ideas, I can see where this is all going. The Ed tech companies want us to “prepare our students for jobs of the future” by becoming prompt engineers.

I look forward to additional book reviews from you. And it looks like you subscribed to my blog. Not much traffic on mine, but I read a lot, and as a writing teacher, about the only writing, I have time to do are my book reviews.

Ah, I agree with you about AI. The pace at which we’re handing over more and more chunks of human creativity to machines is astonishing. I’m hoping that we’ll still value things like art and creative writing even when AI can produce it at the click of a button, in the same way we value the individuality of handmade textiles even though machines have long been able to create flawless results. It’s good to hear that most of your students still want to write in their own words, and I’m sure you’ve been able to pass along some of the love of literature that’s evident from your blog.

Thanks for asking about my books. You could start with my debut novel, On the Holloway Road. It’s old now and was never a huge best-seller anyway so you probably won’t find it in bookshops, but it’s on Amazon etc. It’s about a couple of young Londoners who try and fail to recreate the epic American road trip in the narrow confines of modern Britain.

By the way, ChatGPT tells me that “There Are Rivers in the Sky by Elif Shafak is a richly layered narrative, drawing readers into a world where time, culture, and geography intersect.” Not only that, but “Shafak’s prose flows with a vivid, almost poetic quality,” and the book “rewards readers with a powerful, immersive experience that resonates long after the final page.” So I guess we must both be wrong after all!

I am so glad I found your review.

After all the raving reviews about this book, I was left feeling flat on completion of this book. And I thought, what am I missing?

The story is so loosely brought together, hanging from a desperate drop of water in the last 3 pages of the book!

3 stories with so much more potential, the threads were left hanging.

Grandma Besma certainly did not have a fitting end and I expected much more development of the storyline between the ‘englishman’ and great grandma Leyla from her point of view. But in reality there was no actual story there, it was rushed and did not develop well.

Zaleekah and Narin… Such an underwhelming plot line and meeting of characters. The issue of illegal organ harvesting though a serious one seemed like info dump for this book, it didn’t fit well into the plot and seemed like a last ditch attempt to tie the story together. I expected a deeper meaning or relationship between them.

The concept of the water droplet featuring through the ages in different forms almost felt too forced with too much explanation given to the reader.

I am disappointed in this book, a great idea and great potential but poorly executed with more information than storytelling.

Hi Safiyya, I’m glad you found my review too! It sounds as if you had a similar reaction to mine. I agree, the organ harvesting felt like a sudden, forced insertion near the end. And also agree about the huge potential that didn’t quite seem to be developed. I found the grandmother a compelling character at first, but I also thought that she could have been a more effective link between the distant story of the Englishman and the present day. In the end, it all came down to the drop of water, which just wasn’t enough.

Because she’s not very good – bottom line. Shafak seems to have bewitched European and western audiences with her romanticised, folksy tales of Turkey, but it is not a country recognised by most people who live there. Its Turkey – lite for people who know very little about the modern republic. Orhan Pamuk is in a completely different sphere of ability. Not all of Shafaks novels together as whole can hold a light to the The White Castle, The Black Book or the utterly staggering My Name is Red. I’m mystified as to why respected authors like Ian McEwan, Hanif Kureshi and Arundhati Roy seem to have fallen for her.

Hi Lou, As I mentioned in my post, I’ve enjoyed previous books by Shafak, so I don’t agree that she’s not very good. I do agree with you that Orhan Pamuk is a better writer, but that’s a tough comparison since he’s a Nobel Prize winner. I don’t know anything about how Shafak is perceived in Turkey except for the common snippet that she’s “the most widely read woman writer in Turkey”, so I’d be interested to learn more about that if you can recommend any links. Thanks!

Elif ?afak is not a writer who lives in Turkey. She now lives in London. There is an arrest warrant out for her in Turkey stemming from her book The Bastard of Istanbul. Snippets are not necessarily gospel truth. It is not always helpful and is too subjective to say that one book, or one author, is ‘better’ than another. Such a shame that one has to even consider reviews on AI-generated ChatGPT. Personally, I absolutely love and admire Elif ?afak for the woman she is, her astonishing research abilities and her spirituality and love of humanity. These are great reasons for reading any book.

Hi Suzanne, Thanks for contributing some balance and standing up for Elif Shafak here! I was disappointed in this particular book for the reasons I mentioned in the post, but I have found much to admire in her earlier work, so I’m happy that you came and shared your perspective. She is a much-loved writer, so there are clearly plenty of people who agree with you, even if not many of them have showed up in these comments yet.

A couple of points:

– I think the snippet I referred to was talking about Shafak being widely read by people in Turkey, not saying that she lives in Turkey.

– The ChatGPT comment was just a bit of fun in response to another commenter talking about living in an AI world. Of course you’re right: AI reviews shouldn’t be taken seriously at all.

– Comparing writers and books is certainly a subjective exercise, but I don’t think that means we shouldn’t do it, any more than we should stop talking about which movies we prefer or which actors or singers we think are better than others. We’ll always disagree, but isn’t that part of the fun?

I totally agree with the last comment. I also agree with the reviewer… However, I can forgive Elif Shafak for all the things that didn’t work for me (and they fall in line with the reviewer). This was a story that needed to be told and all the themes need to be discussed. I’m glad Elif wrote the book and glad I have read it through to the end.

Finally I’m back and with hope and fingers crossed that this comment will go through! It was so interesting to read your analysis of the Shafak novel. I’ve only ever read Black Milk, which is nonfiction about motherhood. I enjoyed it very much, but have hesitated to pick up any other books by her without quite knowing why. I read a lot of books that get derailed by excessive research – or the excessive recounting of research, at least – and that on top of a lot of different narratives is definitely an ambitious move. It’s hard to give any element the time and space it requires. I will read Elif Shafak again (I own Three Daughters of Eve), but inevitably with a prolific writer, some novels will work better than others, and I’m glad to have your thoughts on this one.

Hello again! Receiving you loud and clear 🙂 Sorry for the problem with commenting before, but it’s all fixed now, so you can hit that button without worrying that it will all go up in smoke!

The odd thing with the separate narratives here is that one of the characters, Arthur, gets plenty of time and space but still fails to feel quite real. I think it’s because he’s based on a real historical character, and so we get lots of recounting of details Shafak has found about him in the archives, whereas building a character in a novel is about something else altogether.

I’ll read Shafak again too—perhaps I’ll try Black Milk, actually, since I’ve never read any of her non-fiction.

Interesting. I love Elif Shafaks novels, especially 10 Minutes. Last year I read an older book by her, Three Daughters of Eve, which did not work for me. A few pages into There are rivers I was thinking that it fell somewhere in between. But as I kept on reading I was mesmerized and I ended up loving the book.

I thought that the three storylines were intertwined much more than through water, through mythology, history and religion. As for characters Arthur kept growing on me through the book. Anyway, it is always interesting to read other peoples opinions.

Hi Lotten, Thanks very much for your comment. I think the tone of my post has mostly attracted commenters who agree with me, but I know from other reviews that a lot of people loved this book, so I’m happy that you came here to represent that viewpoint. You’re right, it’s interesting to read other people’s opinions. It’s fascinating how the same book can have such a different effect on different people (and even on the same people at different times of life!).

after a strong recommendation i started out on this book and soon felt that i was at the bottom of an 80+ year old’s rag bag of memories and they were to hold together recent (or more recent) history. i was irritated to be reading Little Dorrit and Bleak House as i was later in the book to re-read news stories about the Yazidis. so i wasn’t going to go on with the book until i saw a video clip of the author talking to Mary Beard. Shafek came off best as a charming intelligent woman.

perhaps she just should not write or not historical fiction.

I agree, Shafak comes across really well in interviews and talks. As I mentioned, I’ve also enjoyed quite a few of her previous novels, including some with historical elements, so I wouldn’t agree that she shouldn’t write historical fiction, but I do relate to some of those irritations with this particular book. Thanks for commenting!

expectations of a book…varied; The statement that it is a book of serious literary prowess to be respected and admired…I agree, but it seems in some ways to be an unfinished work. it is a mountain. What was Elif Shafak’s aim? I really enjoyed the book. I finished it and had toured with the text. Both the actual text and the dream trip across time cultures and actual characters trapped me. I was fascinated with each story but must admit that I found it hard to follow sometimes and this was caused by the overdoing of detailed background information. Not only that but the ‘drop’ of water metaphor was worn to death by the end of the book. I listened it to it once, parts of it twice and own a paper back copy. This book is stimulating and enthralling and opens up mesmerising images leading me to want to investigate further. Yes, write the book like this and open the windows of wonders to our world not forgetting the barbarous truths that are sometimes shifted to one side or another in denial or for an easy read.

I also agree, I didn’t love this one. I found the water motif particularly irritating as I am a scientist and the descriptions are often unscientific/scientifically incorrect and it wouldn’t have been hard to get someone to read and correct . It just grated for me, and like you I found it too conceptually loose to draw together the stories.

Oh, that’s interesting to hear, Alison—I didn’t realise there were scientific inaccuracies too. Very surprising that they were not checked in such a high-profile book. Thanks for letting me (and other readers/commenters) know about that.

Hello Andrew!

Five pages into the book and I had suspicions that some of it is AI generated. Came to google to find out whether others felt the same or not. Reading your review, I think I realise it might not be AI, just the disconnection. But the flow is rather unlike any of Shafak’s other books. I have loved every work I read by her till now, so I’ll continue with this to come at my own conclusions.

The Island of Missing Trees is along the same lines as it uses a tree as a character and has a historical background incorporating a lot of research, but it was an absolute joy to read.

Thanks for the review!

Hi Aafiyat, Thanks for commenting. I agree about The Island of Missing Trees, which did share similar features but was a joy to read for me as well. The idea of AI generation hadn’t occurred to me, and I don’t think Shafak would have done that, but I do understand your feeling of something being “off” or different from her previous work. There Are Rivers in the Sky does have lots of fans, but quite a few other people have made it to this corner of the web to share our confusion and disappointment.

I hope you enjoy at least some aspects of the book as it goes on, and I’d like to hear whether your view of it changes later on. So feel free to drop any extra thoughts here as you go along or when you’ve finished.

I concur with the many negative comments. I came to Elif Sharak on the recommendation of friends and ordered this one for no particular reason. I gave up halfway through. The characters are cardbnoard and it’s a preachy sort of narrative. I lost it when Charles Dickens turned up.

Hi Alan, Thanks for commenting. I think your friends’ recommendation was a good one, but unfortunately this book isn’t the best introduction to Elif Shafak. If you’re still willing to give her a chance, I’d recommend one of the earlier novels I mentioned at the end of my post.

Hi Andrew,

Phew, I am not alone!

I want to express the relief and gratitude I felt when I found your review. A friend recommended the book to me and I’ve been struggling with what to say when I return it to her tomorrow. I didn’t want to say I hadn’t enjoyed it without giving her a constructive explanation and you’ve put into words what I want to say. Your three reasons for finding it an unsatisfactory read are the same as mine. I think Elif Shafak has been over ambitious in trying to bring together all the research she has gathered into one coherent whole. I nearly gave up at several points (the Charles Dickens’ moment was one) but elements of the book kept me going, many of which have been described by others. Assyrians, Mesopotamia, Nineveh, Yazidis, all words conjuring up so many aspects of the culture and history of the Middle East but swept away by the allusions to water in its many forms.

I enjoyed “The Island of Missing Trees” and may try “Honour” and “10 mins 38 seconds” if I come across them.

I would also like to say my appreciation of your balanced criticism and the respectful responses you gave to those who have enjoyed “There are Rivers in the Sky”.

Hi Claire,

Thanks for taking the time to leave such a thoughtful comment. It is hard when a friend presses a book into your hands and you don’t enjoy it as much as they did, but I’m sure she will understand.

Thanks also for your comment about the balance and respect. It can be tricky writing negative reviews, and I find it more interesting and useful to think about what did and didn’t work, rather than just “sticking the knife in”. Also, like you, I did find elements of the book that I genuinely liked, which perhaps made the flaws all the more disappointing.

I’m also glad to find this corner of the web! I listened to Are there rivers… on audiobook a few months ago, having previously read Bastard of Istanbul (which I didn’t really enjoy much, but thought maybe I’d picked the wrong book). I felt Rivers was very much a mixed bag – some bits were great, others really not so good and totally agree about the feeling that you’re being taught everything she’s researched, rather than the research being used as a stepping stone for the novel. Anyway, my sister recommended 40 Rules of Love, which I’m reading now, and I find the character & set up of Ella so terribly written, the dialogue so unnatural, I am amazed that people rate this book so highly. The Shams/Rumi story is immeasurably better written, it’s almost like she wrote that with love and then her editor forced her to situate it in the 21st century and so, grudgingly, she wrote a parallel plot. I think this will be the last Shafak book I bother with.

Glad you made it here, Pippa. I didn’t know Shafak had written about the Shams/Rumi story. I’m reading some Rumi poetry now, and there are so many loving references to Shams that I was curious about their relationship, and I think I’d like that part of the novel at least. Sorry to hear that the contemporary part didn’t work so well.

It sounds as if you’ve definitely given Elif Shafak a fair shot at this point! Sometimes it’s just not meant to be. Better luck with your next reading choice!

I’m very interested in your review. I’ve just finished the book, and found it exactly as you described. I wondered if the writer might have played with footnotes/ endnotes to remove some of the clearly research-heavy chunks to a better place. There seemed to be a didactic ‘telling’ when I’d have liked to be trusted more as a reader to sift more myself…more ‘showing’. For example, in the section when Narin overhears her relatives visiting from Germany explain to her Grandmother how their culture works, it seemed a clumsy way of filling in the reader, but completely unrealistic. And there were too many instances of that. It felt as if the book needed a structural shake-up, but also a careful editorial hand at the level of sentences to eliminate matters like ‘ a beautiful paradise’, as if paradise might be anything else. I truly loved learning of Yazidi culture, appreciated the ambition in the plaiting of the narratives, but I felt it could have been so much more. I think it’s hard too when a writer has the very morally courageous mission to open up perspectives on great wrongs, but it does not necessarily lead to a great novel. The ending felt as if the writer had tired of her immense project and it was too pat to feel in any way true. That’s a great pity. However, your review has helped me realise what I hoped/ suspected. I WILL seek our her earlier work. Thank you.

Hi Beth, Thanks for commenting. Interesting idea about footnotes/endnotes! I tend not to like them much in fiction, but they would have been better than the kind of telling you describe in that scene. There were lots of cases like that. I agree about the structural shake-up and sentence-level editing – it could have fixed a lot of the issues and brought out the many positive aspects of the novel. Much of the research could have been relegated to a few telling details or dropped altogether, and other parts could have been shown through the kind of vivid scenes that Shafak writes well.

Anyway, I do appreciate your thoughtful comment – this post has generated some great responses, and yours was a great addition. And I’m glad you still plan to seek out her earlier work. I hope you enjoy it more!

Thanks for the review! Made me feel better as I was struggling to work out why, like yourself, this book has left me cold. That’s an under statement! I never not finish a book but being only 2/3 of the way through I’m tempted to give up. It’s my first encounter with this author. A disappointing introduction, are the others quite so laboured and, in occasions poorly written/edited? 10 minutes 38 seconds … Is worth trying?

Hi Simon, Thanks for your comment, and sorry for the slow response. Yes, I’d say 10 minutes 38 seconds is definitely worth trying. This book is not the best introduction to the author.

Hi Andrew, thanks for your review. I’ve just finished this book after sitting in my TBR pile for a while. I’m now reflecting on the read, as well as the over the top cover quotes (seriously, can any book/author be THAT good?) I agree with most of your comments – except when you say Shafak’s writing is never bad – some of the writing in this book I found obtrusively clunky.

But my final response is almost the opposite of yours. Why were you disappointed? After experiencing the disappointments on the journey much as you did, why do I end up NOT disappointed?

I don’t think this book is anywhere near a masterpiece, but for me it was ultimately worthwhile. Thanks for helping with my reflections.

Hi David, That’s an interesting take. There are definitely worthwhile elements to the book, so I can see why you had that reaction. I’m glad you didn’t end up as disappointed as I did, despite your disappointments along the way!

Good day

While one should carry out a critique of other Author’s works and i totally respect that and believe that to be an objective critique ; i still emphasize that it is the priviledge of the author to touch upon or to deeply get engrosse in an aspect she or he wants reader to notice.

Shafak has experimented with water , rivers , and three or four characters and in the process she has brought about so many trends that are shaping today’s world and society / culture. in my view , author should not be blamed to address all the concepts or constructs in complete totality. Author must have made a plot and the things she wanted to be spoken by the characters. while there are gaps or may i say jumps , i dont find loose ends and author considerably tried to keep in with the links and overall sequnce of things .So while respecting others’ views , i stronly and loudly vote for Elif Shafak and her THERE ARE RIVERS IN THE SKY and she has done a great job like her previous novels … most of which i have read through . Masood

Hi Masood, Thanks very much for this vote for Elif Shafak and her novel. As I said in the original post, I do think she did a great job in her previous novels but was disappointed by aspects of this one. But I like how the comments have shown that every reader has a different take on the book, and I appreciate you sharing yours in such a thoughtful and respectful way.