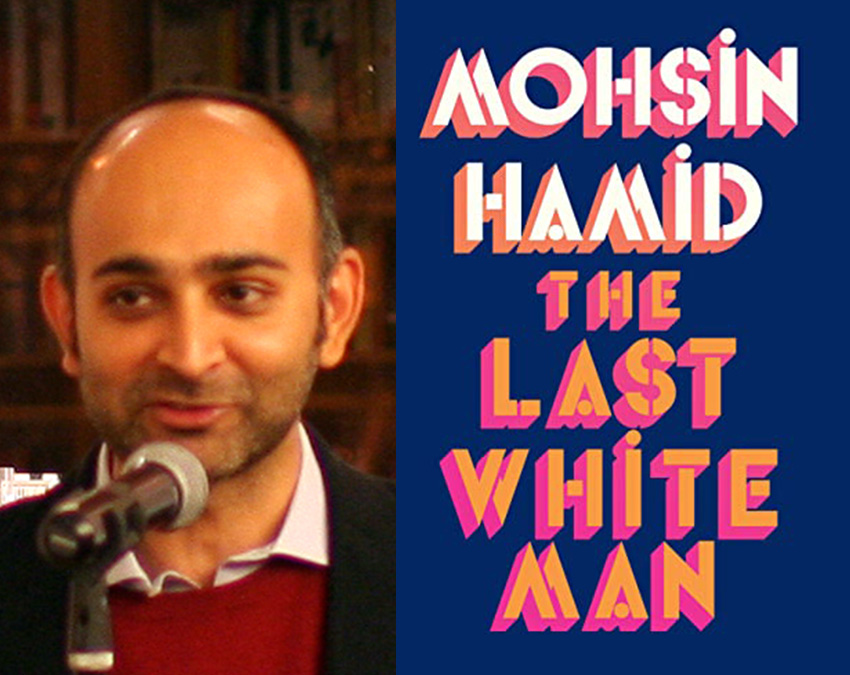

What would happen if white people started turning brown, one by one? Mohsin Hamid explores the question in his latest novel.

The premise of Mohsin Hamid’s latest novel The Last White Man is fascinating: a white man, Anders, wakes up one morning to find that his skin has turned a deep brown. The language is reminiscent of the opening lines of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, and it sets the stage for an interesting exploration of racial identity.

The book centres around Anders and his girlfriend Oona’s attempts to deal with this sudden change, while also coping with ageing and somewhat racist parents. At first, it seems to be just Anders who has changed, but soon it becomes clear that this is happening to other people too. White people all over the town, all over the country (both unnamed) are turning brown.

Oona’s mother believes the whole thing is part of “a plot that had been building for years, for decades, maybe for centuries, the plot against their kind.” And others seem to agree because they form a kind of militia that attacks, threatens or even kills people like Anders who have turned brown. The mood becomes ugly, riots and violence are everywhere, Oona and Anders become afraid to go out.

Then, of course, Oona herself changes, and Oona’s mother, and all the angry people trying to defend whiteness. One by one, everyone changes, and in the end, there are no white people left at all.

It’s a clever idea for a novel—it seems like an exploration of what would happen if the paranoid and misguided white nationalist Great Replacement Theory actually came true, at breakneck speed. The ugly fear and paranoia also reminded me of the “war on woke”—the terror that some people seem to feel when some white people, although not literally turning brown, begin to question the system of white supremacism.

There are a couple of problems, however, that prevented the book from reaching its full potential. The first is the language, which is formed of long, winding sentences held together with commas. For example:

“He sat down on the sofa and after a moment’s hesitation she went and sat next to him, and they spoke, and she could tell he was desperate for reassurance, but she was reluctant to provide it, resistant to being drawn into that role, yet again, not again, and resistant also to lying to him, because she did not know what good it would do, so she told him what she thought, flat-out, that he looked like another person, not just another person, but a different kind of person, utterly different, and that anyone who saw him would think the same, and it was hard, but there it was.”

There’s a drifting, stream-of-thought quality to it that works quite well at first, but I found it quite repetitive over the course of a whole novel. It also seemed to have a strange kind of distancing effect.

The second, larger problem is that both Anders and Oona are muted, passive characters. The metamorphosis that opens the book is so profound that you expect a dramatic reaction from Anders, but it never arrives. He does experience a brief desire while looking in the mirror to “kill the colored man who confronted him here in his home”, but then he just kind of shrugs and accepts what’s happened. He eats a sandwich, calls in sick to work, shops for groceries, smokes some pot.

As for Oona, when Anders first tells her on the phone, her initial reaction is to feel that “she was cashed out, emotion-wise” and to try to get away from him and focus on herself. But she does go to see him for reasons she can’t name, and when she does, their conversation amounts to this:

“So you see? he said.

“Damn,” she replied.

Then they smoke a joint and have sex.

Throughout the book, as society falls apart around them, they still seem to be drifting around in a kind of pot-fuelled haze, reacting belatedly and cautiously to what’s happening, hiding out and stocking up on groceries and waiting for things to blow over.

The supporting cast is not much better. Even Oona’s racist mother, who believes in a huge anti-white conspiracy, doesn’t actually do anything when she finds out her daughter’s boyfriend is one of those who is no longer white. She worries and moans, and finally accepts it. Anders’s father, too, seems like the kind of guy who would reject a non-white son, but he too just kind of grumbles and moans and then accepts it. There’s a lot of violence and drama in the wider world, but none of it really affects the main characters. Even when a white mob turns up at Anders’s home, they just issue a threat and go away again.

Perhaps this is Hamid’s point: that despite all the importance we attach to the entirely invented category of race, it’s really not that big a deal. Maybe he’s showing how misguided the “Great Replacement” scaremongers are: even if the white race disappeared in a few weeks, it really wouldn’t be that big a deal. Here’s how Oona’s paranoid mother develops towards the end of the book, for example:

“Oona’s mother had expected a reckoning and when that reckoning did not come, when those who had been white were not hunted down and caged or whipped or killed … she began to relax, and she found that she did not detest being out among people, no different from the others, not visibly different, not obviously identified as being of one tribe or another, and that it was a kind of reprieve…”

As a political analogy, I get it, but as a story, The Last White Man felt a little dissatisfying. Hamid does such a good job of setting up a brilliant premise and building up an atmosphere of threat and danger in a new and unstable world, and it would have been great to be in the company of characters who interacted with that world in more interesting ways.

There are 4 comments

I’ve been on the fence whether to read this one because it does sound like an interesting set up. But I think I will be just fine with your review 🙂

Hi Stefanie, I know what you mean! I’m still a bit on the fence about it even now – I’m glad I read it, but it’s not one of those books that I’d whole-heartedly recommend.

I think you don’t understand the book! People want to make it a book about raise but to the author that isn’t a big enough deal. It about change how everything changes you can stop the seasons or culture from changing. Everyone get pissed but in the end everyone has no choice but to accept it. I think of it as a study into grieving, everyone grieves the loss of everything because things change and that’s inherently human. It’s OK grieved the loss of a white nation, but you’re not gonna stop it going away. When it does you ask if it was ever their to begin with

Hi Charles, I think there are many different ways of reading and understanding a book, and it’s quite arrogant to believe that only your interpretation is correct and that people with different opinions have failed to understand it.

The odd thing is that we seem to have a lot in common in our interpretations—as I wrote, “Perhaps this is Hamid’s point: that despite all the importance we attach to the entirely invented category of race, it’s really not that big a deal.” That sounds quite similar to your point.