This dual narrative set in a 19th-century Caribbean island is an interesting exploration of a critical period, but the narratives feel unbalanced: we spend a lot of time immersed in the prejudices of the plantation owner’s daughter, while the account of her slave Cambridge feels rushed.

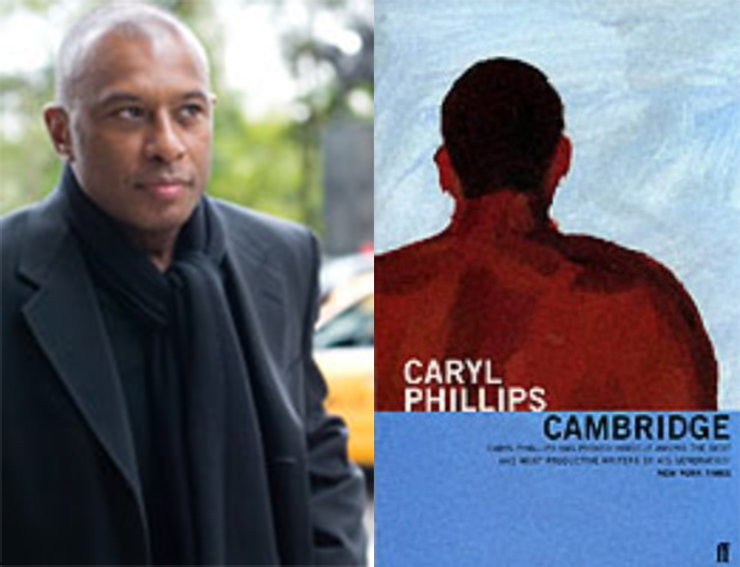

The setup of Cambridge by Caryl Phillips is very promising: we get two perspectives on slavery in the English-speaking Caribbean, one from a white Englishwoman visiting her family’s plantation, and another from one of the human beings she owns.

To some extent, the book delivers on its promise. It’s set in the early 19th century, in the period between the abolition of the slave trade and Emancipation. With the institution of slavery increasingly under attack, the young Emily Cartwright devotes a lot of time in her narrative to defending it, prompted it seems by a combination of racist ignorance, family loyalty, and credulous acceptance of everything she is told by the local whites.

Then comes Cambridge’s account, which completely undercuts Emily’s. For one thing, it shows him to be an intelligent man and an eloquent writer, not the dumb brute she takes him for. And for another, where his account overlaps with hers, it shows events in a very different light from the way she has presented them.

So far, so good. But the problem, for me, is one of balance. The book is 184 pages long, and it’s not until page 133 that Cambridge gets a voice. His narrative is just 34 pages long, and then we get an official document mostly supporting Emily’s version, followed by an epilogue where Emily gets the last word.

It feels unbalanced, especially because Emily’s story is a largely dull affair covering a few months of social engagements and ill-informed diaristic observations, whereas Cambridge’s brief 34 pages tell of his capture from Africa, his first voyage to the Caribbean, his sale and transfer to England, his ten years there mastering the language and converting to the Christian religion, his marriage to a white English woman who’s a servant in his master’s house, the death of his master, his religious tour of England, the death of his wife and child, his missionary trip to Africa, his re-enslavement by an unscrupulous sea-captain, his years and relationships on the Cartwright family plantation, and finally the events that intersect with Emily’s account.

It’s a huge, complex story, and it’s amazing that Caryl Phillips manages to tell it in 34 pages at all. But the result, inevitably, is that it feels rushed. A good reason is given in the text for this, but still, as a reader, I would have preferred to spend a lot more time with Cambridge and a lot less time with Emily Cartwright.

Ultimately, we are left to decide for ourselves which account is true. Phillips presents both conflicting tales to us, alongside the dry official report, and that’s that. For me, it was pretty clear that Cambridge’s account was much more plausible, and I took it to be the real course of events. But the interesting thing about conflicting narratives like this is that it calls everything into question. It’s possible that there are elements of truth and falsehood in both accounts. Different readers could reach different conclusions.

So this was an interesting novel, but I wouldn’t say it was particularly enjoyable to read. Emily is a somewhat sympathetic character, especially at first, but the tedium of her life and the odiousness of her judgments made her 133 pages feel very long indeed, while Cambridge’s sped by in a blur and left me wanting more. In the end, I’m glad I came across it and read it (this was another of my Barbados bookshop purchases), but I wouldn’t whole-heartedly recommend it.

There are 2 comments

Hmm, yeah sounds pretty unbalanced, especially if the pro-slavery person gets most of the narrative and the final word. What do you think the author was up to? Was he trying to make a point? Or are we supposed to think slave owners weren’t really bad people or something?

It’s a good question! I think maybe he was trying to reflect the reality of the times, with Black people’a stories existing only on the margins. And maybe with Emily’s narrative, he is kind of giving her enough rope to hang herself. We get her perspective, but a lot of her opinions and prejudices are quite damning. I suppose he wanted to avoid having the slave owner be a cliche villain, and in a way it’s effective – we sympathise with Emily in some ways, but then we see what horrific things she believes and does. So maybe the point is that a system as evil as slavery corrupts even people who might otherwise have been good.

Thanks for the question – it prompted me to think about the author’s motives and maybe see some more merit in them ?