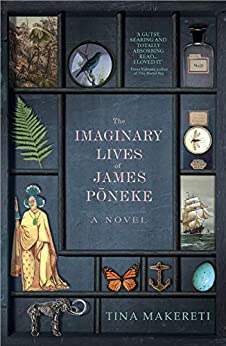

Set in Aotearoa and London some time in the 19th century, Tina Makereti’s excellent novel tells the story of a Maori boy who makes his way to London, where he is exhibited in an artist’s show. But he soon begins to turn his own critical gaze on the city and people that claim to be at the heart of civilisation.

As part of Indigenous Literature Week, here’s my review of The Imaginary Lives of James Poneke by Maori author Tina Makereti.

The violence of colonisation can take many forms. There’s physical violence, of course, in the form of land grabs, murder, rape, mutilation, and other forms of terrorism. There’s psychological violence: the colonisation of the mind of its subjects with the insidious idea that they are innately inferior. There’s cultural violence: the destruction of traditions that have evolved over centuries or millennia, the colonisation of language, etc. There’s spiritual violence: the imposition of a foreign god and the insistence that local beliefs and practices are the works of the devil. There’s economic violence: enslavement, exploitation, the appropriation of goods and raw materials, etc. The list goes on.

In The Imaginary Lives of James Poneke, Tina Makereti explores most of these forms, but her focus is mostly on the violence of the colonial gaze.

Set in Aotearoa and London some time in the 19th century, the novel tells the story of a Maori boy whose whole family is killed in the chaos of war between local tribal groups and displacement by the advancing British colonial forces. Hemi aka James Poneke eventually makes his way to London thanks to an English artist who uses him as a live exhibit in his show, where he is poked and prodded and scrutinised as a “savage”.

But Hemi is not content to remain a victim. He also turns his own gaze on the people of London, overturning the power dynamic and rebelling against the role he has been allotted. He plays his own part, seeks his own education, his own experiences. And this is his memoir, his story told in his own voice, and he has a lot to say about the city that claims to be the heart of civilisation.

At the heart of the book, especially in its early and middle stages, is the relationship between Hemi and the English artist, known only as “The Artist”. It carries strong overtones of cultural appropriation, as The Artist travels all over Aotearoa creating portraits of Maori people while showing very little knowledge or understanding of their lives. Worse than that, he’s not even interested in their lives or in the meaning of the cultural objects he portrays in his sketches. All he cares about is getting back home to England, exhibiting his drawings in London, selling his book, and achieving the fame that will justify the whole expedition, so that he can repeat the whole process in South Africa.

And that’s where Hemi comes in. He attaches himself to The Artist, hoping to travel with him and see the world and get an education. When he finally asks to go with him to England, this gives The Artist an idea:

“James, what do you say you join in? A living exhibit! A chief’s son – my drawings made real!”

And so James Poneke becomes an exhibit at a gallery in Piccadilly, playing the role of a Maori chief for the delight of the English public. In his spare time, The Artist’s father and sister take him to see sights that seem uncomfortably close to his own role: animals in a zoo, peep-shows made of layered paper, parks in which nature is eerily controlled and manipulated, stuffed animals in a museum, etc.

At first, he is mostly bored during his appearances, and in his boredom he begins to observe the people around him, just as they are observing him.

“I had already begun to think it was not me they came for but the idea they had of someone like me.”

“Only the boldest asked me questions directly, but those questions seemed posed not necessarily to hear my answer but to observe the novelty of my reply.”

“They had come to view some far-off part of the world in the Artist’s paintings, and some other kind of person in me, though in the end I think they came only to know themselves, to understand their own thoughts and see their world or their selves reflected in our images and faces.

Gradually he begins to observe the class differences, too, and notices that those with shabbier clothes often look at him more as a human being, or even with a spark of recognition. It’s when Hemi finally makes a friend, Billy Nelson, and goes out among the poor and working classes, that he discovers “a splendid tribe, not unlike the tribes I had known at home, and I felt warm in the cradle of it.”

As he explores this new world with his new friends, he loses his boyish admiration of The Artist and begins to see him for what he is:

“He had taken what he wanted from my land, and now sought to do the same in other lands: once his book sold, he would be done with us. As I felt his interest wane, so did my own.”

In the world of working-class London, far beyond the museums and scholarly gatherings, Hemi finally receives the education he’d wanted all this time. He comes to understand the world and himself in new ways, some of them exciting and some extremely painful. He travels across oceans, and he ends up back at the home of The Artist’s family, where he narrates the story that will become The Imaginary Lives of James Poneke.

The narrator of the story sounds like an old, tired, jaded man, so it’s quite jarring to learn that he is still so young when he’s telling the story. I think this is a great way of showing the toll that his experiences in London have taken on him. And yet, for all the various forms of violence to which he is subjected in this book, James Poneke is never beaten. He is damaged by everything he goes through, but not broken. He never loses the boldness, the thirst for new experiences that carried him so far from where he began. He’s a compelling narrator, and this is a wonderful book.

Indigenous Literature Week runs until 11 July, so there’s still time to write a review if you want to take part. Or you can participate by reading and commenting on other people’s reviews for Indigenous Literature Week.

There are 4 comments

This question of stolen artifacts, even more so when they are not objects but living human beings, is such a great lens through which to view colonialism, isn’t it. To really bring home how cruel and inhumane the practices were. I mean, it’s unethical if it’s a totem pole, eh? But maybe not everyone readily recognizes how different beliefs endow different kinds of objects with cultural meaning…but with a person, undeniably unethical. I’ve got this one on my TBR and can’t remember how it got there now, but obviously for good reason!

Yes, the “living exhibit” idea in the book was very powerful for bringing home the hugely problematic nature of this kind of way of seeing people and appropriating their sacred objects with no respect. Makereti does a great job of exploring the complexity of cultural appropriation through the character of The Artist, and Hemi’s relationship to him is well drawn. She makes the unequal power dynamic clear, without making Hemi into a powerless victim. I’m glad it’s on your TBR, and hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

This is a marvellous review… thanks for contributing Andrew:)

Thanks so much, Lisa. And thanks for arranging the event – I really enjoyed participating!