Here’s a little life tip for you. If you ever feel that the time is starting to drag and you’d like your life to be busier, try signing up for a blogging event. As soon as the dates roll around, you’ll find your life getting so hectic that all your plans for diligent participation go out of the window.

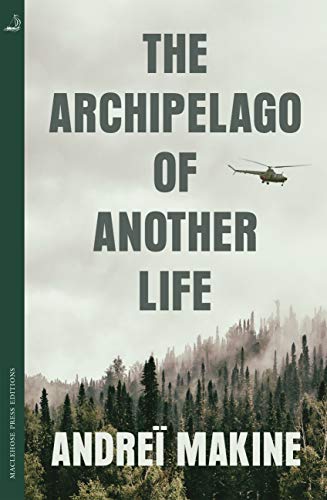

That’s why, of this four-part readalong of The Archipelago of Another Life by Andreï Makine, you’ve only seen evidence of Part 2 and, now, Part 4. My only contribution to Part 1 was a belated comment on Carol’s blog answering a few of the questions, and Part 3 passed me by altogether.

But why dwell on the past? Here are my answers to Emma’s questions on the last part of this intriguing story of chases and pursuits in the Siberian wilderness.

1) The last quarter features several walks (Pavel and Elkan, then Pavel by himself, then again with Elkan; then Pavel and the teen; and the trip with Sacha). How similar/different are the last ones from the other walks we have seen before? What do you think the author is trying to convey?

As we’ve discussed before in this readalong, we can read the journeys in The Archipelago of Another Life as taking place on several different levels: physical, political, spiritual. In all three cases, the goal is a freedom which seems elusive, even impossible at first. So the journeys we see in the earlier parts of the book are difficult, confusing, and long, with lots of changes of direction and general disorientation.

In the last part of the book, the journeys are noticeably easier. First, Pavel turns back to return fearfully to the life he knows—a reaction that will be familiar to anyone who has attempted any of the three types of self-liberation. Of course, it’s easy to go back, much faster to undo something than to do it.

After his time in “the world where men hated one another so much” turns out to be a disaster, he returns quickly to Elkan because he is now familiar with the terrain and it doesn’t scare him as it did the first time, when everything was unfamiliar and intimidating. He knows now exactly where he is going.

And in the later journeys, both Pavel and the narrator are older and wiser, so the bewilderment and disorientation is gone and the progress is faster. On the trip with Sasha, the sea gets rough for a page or two, but that’s it. The initial journey that took most of the book is now accomplished several times in a fraction of the time. So I think this shows the growth and maturity in the characters.

2) Any comment on what’s awaiting Pavel at the military camp?

It’s a perfect indictment of the Soviet regime and other oppressive systems: the people who tell the truth are tortured and beaten and branded as traitors because their truth threatens the lies by which their superiors have profited.

It’s also the moment when Pavel finally achieves liberation from his subservience to the system, symbolised throughout the book by the image of the rag doll. Now, as he is being beaten by the enraged Ratinsky, he feels no fear:

“Dumbfounded, I discovered that the ‘rag doll’ had vanished!”

After this, everything seems easier: his escape, his return to Elkan, his life on the island, in a gentler world of mutual refuge from hatred and violence. Perhaps he needed to go back to the camp to truly escape from it.

3) There’s again a huge place given to nature and wilderness in this last part. What is the author’s message through it?

I think Makine positions the wilderness as a utopia, partly in the modern sense of a desirable state, but with more of the shade of its original Greek meaning of “no place”. The wilderness is a place that doesn’t exist, a place completely outside of and in opposition to civilisation, which Makine shows in this book to be quite uncivilised. It’s significant that the islands are a place where some kind of magnetic anomaly prevents even compasses from working, and that the short stretch of sea separating it from the mainland is plagued by dangerous currents.

Life in this wilderness is harsh and difficult, and yet stepping outside of civilisation exerts an irresistible appeal on Pavel, Elkan, the narrator, and Sasha too. They want to liberate themselves from a world of hatred and violence, a world where the truth gets you killed and lies get you promoted, and return to something simpler: human cooperation, compassion, tenderness. They want to find, or fashion, their own utopia.

After describing the wars and violence, the injustice and hatred, Pavel denounces “the farcical charade of a world in which men have lived in mutual hatred since the beginning of time.” The narrator then delivers a beautiful line which, I think, makes clear what the wilderness represents:

“Their exile was less about a fear of being arrested and thrown in a camp than it was about a refusal to take part in any such games.”

4) What do you think about the structure of the book?

I loved how all the journeys across the wilderness intersected with each other and echoed across time. I think, if we return to those three types of journey that I think Makine is talking about, they all involve walking in the footsteps of others, following the signs that they’ve left along the way. And, with the passage of time, our role often changes: we move from the eager pursuer to the older, wiser fugitive/guide. The narrator learnt his survival skills (and a lot more…) from Pavel, who learnt from Elkan, who learnt from how many numberless people who had made the same journey in the past?

5) Did you find the last sentence was a satisfactory ending?

Yes. For me, it was a beautifully balanced ending. It wasn’t a Hollywood “Pavel and Elkan survived after all!” ending, but it did give a fragile, tender sense of hope, even as the narrator acknowledges that it’s “barely realistic”—a bold admission for a novelist to make about his own ending, but one that I thought worked brilliantly to balance hope with realism.

The idea of the “most beautiful trace that a love between two people could leave among the living” was also a lovely note to end on. So much of what we do as human beings is about leaving a mark, like dogs peeing on trees. And yet, ultimately, what is left when we are gone? A sail half-glimpsed on a distant sea seems about right to me.

In any case, what matters is not the trace, but the love itself, and the hope it represents for a better world, dominated not by the violence and lies of Ratinsky but by the brave souls who manage to liberate themselves from “that rag doll lurking within every one of us, stirring up our fears, our desires, our selfishness”.

Such a world may be “barely realistic”, but as the daily newspapers chart our steady march towards an unliveable climate, perhaps it’s time to realise that our current “rag doll” way of life doesn’t have much of a future either.

6) How do you now understand the title? What do you think is the author’s ultimate message of his book? Do you agree with him?

I wonder if The Archipelago of Another Life is intended as a reference to Solzhenitsyn’s famous Gulag Archipelago. We all know the horrors of that archipelago, but what’s the alternative to that? I think it’s what the characters in the book are trying to find, the archipelago of another life, not of violence and domination but of love and compassion.

If that’s his message, then yep, sign me up! I think that, as difficult as it is to find our way to that archipelago, and as much as we might get lost along the way, we have no choice but to try.

7) Did you like this book, why or why not?

If you’ve read this far, you probably know what my answer will be. Yes, I loved it. I loved the complexity of the ideas, the layers of meaning, some of which we’ve uncovered in this readalong but plenty of which I’m sure are still out there in the text waiting for the next curious reader to discover them. And I loved the way Makine broadens The Archipelago of Another Life out beyond a critique of the Stalinist USSR into a comment on civilisation itself, with the oblique references to Vietnam, Baghdad, Belgrade, pollution, atomic bombs, etc.

And interestingly enough, I loved the novel much more after writing down my thoughts and reading Emma’s and Carol’s responses too. I tend to be a quick reader, and the pressures on my time mean that my reviews in recent years haven’t been as detailed as they used to be. So it was good to spend more time with this novel, with some good questions to prompt my thinking, and to understand and appreciate it a lot more.

So I guess that, despite the lack of time and the way I got overwhelmed and had to rush or skip some of the parts, maybe signing up for blogging events is a good idea after all. When’s the next one?

There are 6 comments

Yes, life often has plans of its own, not always compatible with book blogging! So I’m glad to see you back and read your comments for the end of the book.

2/ “Perhaps he needed to go back to the camp to truly escape from it.” Good point!

3/ I also noted this sentence. I find this reaction in other contemporary French authors, especially Serge Joncour (Wild Dog; Nature humaine) and Sylvain Tesson (Sur les chemins noirs; The Consolations of the Forest; and many more).

I like that you found a symbolic meaning to the real magnetic phenomemon.

4/ Very nice how you highlight this handing our of wisdom.

5/ I totally agree with you about the ending.

6/ The reference seems so obvious, how come neither Carol nor I mentioned it!! And in French, it’s the same word “archipel” used in both works.

7/ Like you, I tend to read quickly, and many books at the same time, and I’m taking less and less time to review. So it was also so much more enriching for me to slow down, reflect, and take time to put my thoughts into words.

I have recently participated in readalongs with another blogger, Julie Anna from https://www.sincerelyjulieanna.com/. We have just read the classic scifi by Michael Crichton, The Andromeda Strain (https://wordsandpeace.com/tag/the-andromeda-strain/) and before that the recent Japanese title Before the Coffee Gets Cold (https://wordsandpeace.com/2021/04/04/before-the-coffee-gets-cold-read-along-part-3/).

I am planning to read something else both with Julie Anna, and with Carol, maybe in September. We would definitely appreciate your participation. Let us know if there’s any genre or particular title you would be interested in.

Thanks Andrew for participating, and thus enriching our reading with your own perspectives.

I’m going to add the link to your post on my own post

Thanks for the comments, Emma! I don’t know Joncour or Tesson, but those works sound interesting—I’ll look them up.

I’m going to read your post now—I held off until I’d written mine because I didn’t want to end up giving the same answers 🙂 I’ll be interested to see your responses.

I’d love to participate in another readalong—as I said, I got a lot out of this one. But I’m hoping to start travelling again in the next few months, and when I do, I’ll have even less time than I do now. So for the September readalong it’s probably best to proceeed without me, and I’ll join in at the last minute if I have time. I follow your blog by RSS, so I’ll see the announcement.

Thanks again for organising this, Emma, and for the thought-provoking questions!

Heheh It’s true, having a deadline always makes everything else busy. Agreed, that reading “in company” always leads me to a different kind of appreciation too. One of the wonders of the ‘net, especially for those of us who didn’t have reading friends as kids!

Yes, reading was always a very solitary pursuit for me as a kid. I loved that retreat into my own world, or the world of the author—it felt very intimate. But there’s a lot to be said for sharing the pleasure. Genie and I sometimes read books to each other aloud, alternating chapters, and that’s a lot of fun. The reading often gets interrupted for comments, appreciations, disagreements, etc.

I’m so glad you joined Andrew. Your comments have definitely enriched my experience. I’m still not enough of a romantic to be satisfied with the ending but your interpretation appeals to me at an intellectual level. I lack the imagination necessary to have seen the ending as you did but your description makes me appreciate the beauty of it.

I also loved the book and I think I would have even if I’d read it alone. Perhaps this just shows the power of Makine’s writing. He covers all the bases such that skeptical or orthodox or artistic minds can all appreciate the narrative.

I’m glad too, Carol. Thanks for your insightful questions and responses throughout! I know what you mean about romanticism, but I don’t consider myself a romantic; I think I’m more realistic than the realists 😉 Anyway, you’re right that Makine’s writing works at multiple levels, which is one of the great things about this book.