The Vastness of the Dark seems to be a quite simple tale about a young man escaping from the confines of his family to find freedom, but it becomes something more complex in the last few pages.

Alistair MacLeod was a Canadian writer who told stories about the rugged landscape of Cape Breton island in Nova Scotia and the rugged miners and fishermen who inhabited it.

Marcie over at Buried in Print has embarked on a fascinating reading project covering all of his short stories over the next couple of years. I probably won’t be able to join her for all of them—I have my hands full with Borges, among other things—but I wanted to drop in and read along with her this month.

This month’s story is The Vastness of the Dark, a story that seems to be a quite simple tale about a young man escaping from the confines of his family to find freedom, but that becomes something more complex in the last few pages.

MacLeod’s prose, like the story itself, seems simple but is actually quite complex. There are no stylistic fireworks here, but every word seems carefully chosen, and even the simple language conveys a boatload of meaning.

For example, we start with a beautifully detailed description of the narrator’s father lying in bed:

“lying there on his back with his thinning iron-grey hair tousled upon the pillow and with his hollow cheeks and even his jet-black eyebrows rising and falling slightly with the erratic pattern of his breathing.”

The description goes on, taking in the bubbles of saliva at the corners of his mouth, the way his left arm and leg are hanging over the bed and touching the floor, as if ready to respond to an emergency.

But the interesting thing is that the narrator hasn’t seen any of this. He’s imagining “how he must be”, and he goes on to imagine how his father will get up and go downstairs, and we get another highly detailed scene told in the future tense as his father struggles to button his trousers with the three remaining fingers on his right hand while holding his shoes in his left, etc.

The only way the narrator could know all this detail without seeing it, of course, is because he has seen it so many times before, and it always happens in exactly the same way. It’s a wonderful technique for showing us the suffocating familiarity of this repetitive, predictable, intimate life lived in a very small house with a very large family.

The narrator, James, is the oldest of eight children, and it turns out that his birth was unplanned. His grandfather lets that fact slip one night while he’s drunk:

“when I heard it I said, ‘Well, he will have to stay now and marry her because that’s the kind of man he is, and he will work in my place now just as I’ve always wanted.'”

So by being born, James effectively trapped his father into staying in this small Cape Breton town and working in the same mine as his grandfather. And now the mines have closed and the jobs have gone, and there’s nothing left for his father to do but get drunk and violent and to keep waking up early every morning and banging the stovelids in the kitchen in a futile pretence of having somewhere to go.

As for James, there’s nothing here for him at all. He feels like a prisoner, oppressed by the family’s mining tradition, which dates back to 1873. There’s a clear meaning behind his description of the blind old pit-horses his father used to take him to see:

“They had been so long in the darkness of the mine that their eyes did not know the light, and the darkness of their labour had become that of their lives.”

And so, when he turns eighteen, James makes his escape from this place. But here’s where The Vastness of the Dark gets more complicated.

As James hitch-hikes away from Cape Breton towards an unknown destination, he gets a ride with a coarse, brutish man who speaks disparagingly of the grim mining towns they’re passing through and boasts of his sexual conquests. But the towns remind James of his own, and the women remind him of his own mother, and so it is as if he’s seeing his own life from the outside. And then he sees the people in the street looking at him in this car with Ontario licence plates and dismissing him as an uncaring outsider.

This process of looking through the glass, of seeing and being seen, helps James to realise that he can’t so easily be free of his family and his upbringing simply by leaving town. He is not the outsider and never will be—he is of this place, even when he’s trying to leave it.

“And perhaps I have tried too hard to be someone else without realizing at first what I presently am.”

And at the same time, as a reader, I realised that James had barely spoken in the whole story. He is the narrator, yes, and so we have access to his thoughts and experiences, but almost all of the dialogue involves other people talking to him while he listens silently or gives terse responses. And that seems to be another way in which MacLeod is showing us how fragile this young man’s identity is, how he is still being shaped by those around him, and perhaps he won’t truly find freedom until he learns to shape himself.

The Vastness of the Dark, then, is a short story that gives us plenty to ponder, plenty to chew on. It’s one of those stories in which not much seems to be happening, but then you realise you’ve covered a lot of ground, and it all felt quite effortless.

I didn’t know Alistair MacLeod or his writing before Marcie began her reading project, but I’m very glad I do now. Why not join in for a story or two yourself? You can find details of the reading project, or get the Buried in Print take on The Vastness of the Dark. (Update: Naomi at Consumed by Ink also wrote an excellent post.)

There are 12 comments

I like what you say about James seeing his own life from the outside. I did not like that guy driving him, but I guess he served his purpose.

I absolutely loved the descriptions James gives of his family as he lies in bed. And those other children – will they be sad when they find out James is gone? Or maybe the oldest will be glad to have his bedroom, and it will go on like that until the youngest is 18…

Hi Naomi, Oh, that guy! He must be one of the least likeable people ever to appear in the pages of fiction. But you’re right, he does serve a purpose. I think he helps James to see who he is, and who he’s not.

Yes, I wondered about the other children too. It was all so abrupt, wasn’t it? A whole life, and then one morning, “I think I’ll be leaving now.” I did like how he showed the parents stumbling towards saying something affectionate but unable to get beyond indirect stuff like the mother saying she was going to bake a cake. Not very emotionally expressive people, to say the least!

Just how close to Cape Breton are you, Naomi? I’m guessing close enough to have experienced some of this “talking about baking cakes instead of talking about love” kind of “affection”? I know there’s a good bit of that in my family’s history, and only half of my lineage is similar to yours and half a continent away at that. Feel free to deny everything and supply cake recipes instead! 🙂

We are about a two hour drive from the causeway to Cape Breton. And there are a LOT of Cape Bretoners in Truro.

Huh. I’ve never really thought about our family’s affection habits. It’s funny, though, because it’s true that we didn’t talk much about love and emotions growing up, even though I felt the love. I never once felt unloved or like my emotions were being suppressed. So, apparently, talking about cakes works just as well! 🙂

I’m voting for a series of kids moving in/out of that bedroom. That’s something I was wondering too! That guy was SO believable. His statement about the woman/girl’s mouths felt like a slap!

Yes!

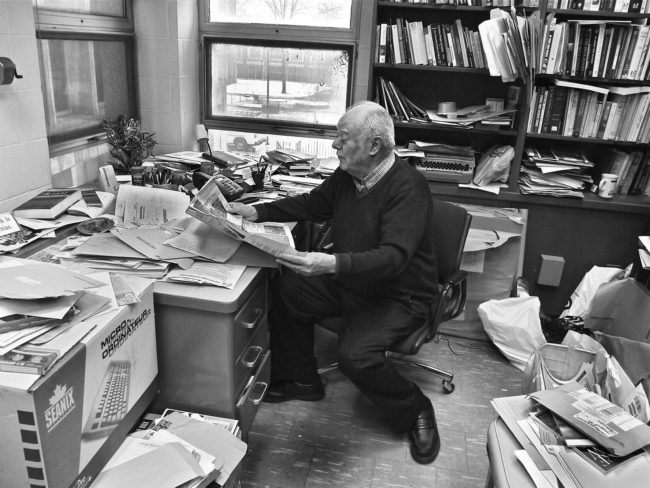

I love that you’re writing about the great Alistair MacLeod! I grew up in Windsor, Ontario with his daughter, Marion. I was often at the house sharing meals and stories with the heaping family of kids. Alistair’s quick wit and burning red cheeks startled me at times, but I knew I was in the space of someone great. His papers spilled out of his home office like fingers trying to grab us. He is a master writer and is missed here and abroad. So great to read that Marcie is working on a project about him. His son, Alexander, is a fine writer as well. The others…excellent musicians, parents, friends…

That’s amazing, Vanessa. What lovely images are conjured from the memories you’ve shared. I was born in Windsor but didn’t live there long, although visited a fair bit over the years; I should likely have mentioned more about his connection to that city, via the university, but it seemed simpler to stick with Cape Breton. Maybe it’ll come up later in the project, with stories that have more of an Ontario element.

Thanks so much for this comment, Vanessa. It’s great to get a little glimpse of his home life. I love the image of his papers spilling out like fingers trying to grab you!

I didn’t know that his son was a writer too—I’ll look up his work.

Alexander MacLeod’s stories are also SO GOOD.

I have a feeling that, as many readers as there could be for one of Alistair MacLeod’s stories, that each of those readers could write about just a few of the elements in the story and never (or barely) brush against what another reader had chosen as a focus. It’s trite, but when people speak of whole worlds existing inside a few pages of a short story, this is the kind of writing that creates that expansiveness; I’m so glad that you are enjoying his work and are pleased to have made the discovery. (Also, I love the header of your post!) I had to check my own post to see if I had included the bit about James’ conception out of wedlock (I’d deleted it) but I’m glad you mentioned it because it casts the whole story and the questions of inevitability and legacy into quite another light. And you have a sense, after you come to know this truth behind his parents’ marriage, that much of the story actually rests on this question, this detail, that’s never been spoken aloud. What does it mean to his ideas about belonging, to his sense of feeling obliged to remain, if his conception was an accident? Maybe nothing, maybe everything. I also appreciate your observation of the “suffocatingly familiar” and the idea of James being sketched largely through others’ eyes.

You’re right about that, Marcie. There’s so much in each of Macleod’s stories to look at and think about. I’m very glad you introduced me to him!

That’s a good point about his conception too. I’d been thinking of it more in terms of being trapped—his birth trapped his father in that small world, and James doesn’t want to get stuck there as well. But you’re right, it could affect his sense of belonging as well, to know that he wasn’t “intended” for this life in the way that his younger siblings were (and we get a lot of information about their conception too—it feels as if we can count the strokes too!).