Homs is one of those places that, like Aleppo and Kandahar and Mosul, has become a byword for suffering. For years it appeared on the nightly news with images of corpses, rubble, wailing widows and intrepid reporters ducking as a shell lands close by. In my childhood, Beirut and later Sarajevo were similar shorthand for misery, along with Belfast during the Troubles.

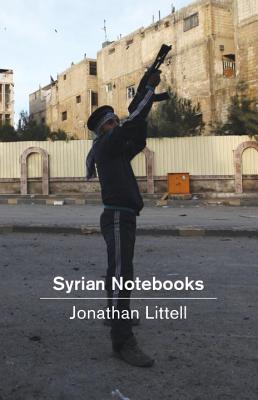

In Syrian Notebooks, Jonathan Littell takes us inside Homs for a couple of weeks in 2012, early in the Syrian uprising. He gives us a glimpse of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) when it was just starting to grow out of the peaceful protests against the Assad regime, when it was just a few isolated bands of army deserters and the volunteers trying to protect people from the brutal attacks by the security forces.

The seeds of violent sectarianism and religious extremism can be seen in some of the interviews and events, but at that time they were only seeds and might not have grown. Resentment of Assad’s brutal government was the motivating factor for most of the fighters and protesters, not hatred of a sect or religion. An interesting insight of Syrian Notebooks is the degree to which the Assad regime actually fostered the sectarianism and extremism that came later, believing that this policy would divide and weaken its enemies and make them easier to deal with.

Pros and Cons of the “Notebook” Approach

The name of the book is apt—this is pretty much a reporter’s notebook, transcribed and presumably tidied up a bit (the language is more coherent than I’d expect from notes made in a war zone), but otherwise untouched except for a few notes and explanations in italics.

This is both a strength and a weakness of the book. The downside is that, along with the interesting insights, we get a lot of mundane detail about passing checkpoints, arranging interviews, getting from A to B, ordering food, and even Jonathan Littell’s dreams. But there are also several advantages to this approach.

The first advantage is that we get an accurate snapshot of a place and time, undisturbed by retrospective judgments. For future historians of the Syrian conflict, Syrian Notebooks will be a valuable source.

Secondly, we get an inside look at a reporter’s process in a war zone and see how difficult it is to verify the truth of anything.

Littell is very clear throughout the book that the Syrian government is committing atrocities, against the people of Homs—he sees the sniper attacks, visits makeshift hospitals and see people being brought in with bullet wounds and worse. That much is beyond doubt.

But some of the details are less clear. Littell also knows that the FSA activists on whom he relies for access are also keen to push their own agenda and convince the West to intervene on their behalf. And the government, of course, has its own agenda, and individual factions have their as well.

The conscientious journalist must be aware of the vested interests of every source and try to verify every claim independently. But it’s incredibly difficult to do that amid the chaos of war. Syrian Notebooks gives a good insight into a journalist doing his best to sift through a mass of unreliable, partial, biased information and reach an approximation of the truth.

The third advantage of the unfiltered notebook approach is that we get to meet people who didn’t make it into Littell’s stories in Le Monde, but who have important stories to tell nonetheless. This is another reality of journalism: you always gather more facts and stories than you can possibly include in the final piece. What makes it into the story is not necessarily more important than what you left out: it just fits the story better. So Littell has lots of extra material, much of it compelling, and it’s good to see it get published here.

Some of his sources tell their stories in detail, like Abu Abdallah, a military doctor who resigned in disgust after seeing wounded demonstrators being tortured. His role involved, he said:

- Keeping torture victims alive so they can be tortured longer.

- Giving first aid when the person passes out, so that the torture can continue.

- Supervising the use of psychotropic drugs during interrogation.

- Taking prisoners to hospital when they are in danger of death, and saving them if they are important enough.

Others, like Mahmoud, a ten-year-old boy who danced and chanted slogans on the shoulders of grown-ups during the demonstrations, appear only fleetingly. But their experiences have been recorded anyway, and there is a value to that, especially as the situation in Homs deteriorated after Littell’s visit, and many of the people he describes may no longer be alive.

Syrian Notebooks: My Verdict

If you want an understanding of the Syrian conflict as a whole, this is not the book to read—at least, not in isolation. But if you want an in-depth look at a particular moment in time—Homs in early 2012—as well as insights into the process of being a war reporter, this is a fascinating and worthwhile read.

If you want to read a different kind of war reporting, see my review of Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia. And please subscribe to my newsletter if you want to stay updated.

There are 2 comments

The Syrian conflict is such a tragedy. It is also complex so I think that books like this that only tell part of the story are important too. It sounds like this one recounts some pretty horrible stuff.

You’re right, Brian – books that tell part of the story have an important part to play in piecing together what happened and why. I can see this book being a very useful source for some more comprehensive histories of the conflict.