This month, I am reading Joseph Roth’s novel The Radetzky March in the excellent company of fellow book bloggers Caroline and Lizzy. The readalong takes place over three weeks, Roth having helpfully split his novel into three parts just for this purpose.

This week, I read Part 1, and I am responding to questions that Caroline and Lizzy came up with as prompts.

Welcome to the #germanlitmonth spring readalong of Joseph Roth’s most famous novel, The Radetzky March. What enticed you to readalong with us?

A strange sequence of coincidences. I was in a second-hand bookshop a few years ago and came across Roth’s book The Hotel Years, and it appealed to me because the title describes how I have been living since 2015, with no permanent home, travelling around Europe and living in hotels.

But then the book languished in boxes and suitcases and I didn’t read it until last September, so it was still fresh in my mind when German Literature Month came around and Caroline mentioned reading The Radetzky March together. I loved Roth’s prose in his feuilletons for The Hotel Years, and I wanted to see what he did in a full-length novel.

Plus I loved the Effi Briest readalong that Lizzy and Caroline organised back in 2011, so I immediately signed up!

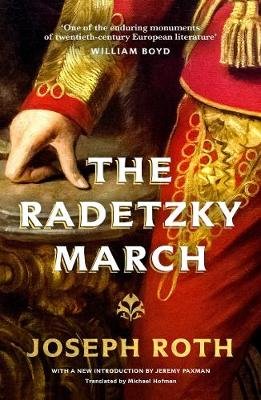

Which edition/translation are you using and how is it reading?

I’m reading the Granta edition, translated into English by Michael Hofmann. He’s the same translator who rendered Roth’s prose so beautifully in The Hotel Years, and he’s doing a good job here too. Hofmann has translated loads of Roth’s work into English, and it’s good to have a translator who knows a writer’s work and style so intimately.

I haven’t read the original German so I can’t say how faithful Hofmann is to Roth’s style, but I can say that it’s a pleasure to read in English.

Is the novel living up to your expectations?

I wasn’t sure what to expect. A novel is so different from a short newspaper article, and I wasn’t sure what Roth would do in a longer form.

I am a little surprised at the way The Radetzky March reads to me like a 19th-century novel, even though it was written in 1932. It has a broad historical sweep, a confident omniscient narrator, a traditional narrative style. There’s no hint of modernism that I can detect.

The novel is doing an excellent job, though, of pulling me into the story and creating a world that feels entirely real and believable. And it’s amazing to look back on Part 1 and see how many dramatic events were packed into it, even though the pace felt quite languid. That’s quite an achievement.

How would you comment on the first few sentences? Is this an effective opening?

“The Trottas were not an old family. Their founder had been enobled following the battle of Solferino. He was a Slovene. The name of his village – Sipolje – was taken into his title. Fate had singled him out for a particular deed. He subsequently did everything he could to return himself to obscurity.” (Translation: Michael Hofmann)

For me, it wasn’t effective at all. In fact, I think I zoned out somewhere in the first few pages and had to go back and reread from the beginning.

Part of it is due to the passage of time. Styles have changed, attention spans have shortened, and novels now try to hook the reader much more quickly—something that Roth was good at, actually, in his newspaper articles, but presumably didn’t think it was necessary to do here.

Another result of the passage of time is that the battle of Solferino, which would have had great resonance at the time, meant nothing to me. Now I know that it was a historic defeat for the Austrian Empire, so it sows the seed for the subsequent decline of both the empire and the family even at this moment of heroism. I like the part about fate and obscurity too, in retrospect, but on a first reading it just all felt too abstract.

Roth subscribed to Chekhov’s view that a writer “should not be a judge of his characters or what they say, but an impartial witness”. That doesn’t mean that we as readers need to be the same! How do you feel about the hero of Solferino’s crusade to return to obscurity? What are the ramifications of this for his descendants?

His actions struck me as quite extreme, and they’re the only part of the book so far that didn’t feel very believable. To throw in his whole career over a slight misrepresentation in a children’s book is an extreme reaction.

I can see what Roth was saying about the man’s absolute, quasi-religious faith in the monarchy and his feelings of betrayal and disgust when it showed itself to be capable of even the smallest dishonesty. And he also seemed uncomfortable with his sudden fame and was perhaps looking for an excuse to get rid of it. But I struggled to stay with the novel at this point.

The ramifications for his descendants are quite considerable. His prevents his son from joining the military and forces him into a career as a bureaucrat. And the son’s suppressed desires get passed on to the grandson, who is funnelled into the military from a young age even though he never seems suited for it.

Such is the power of fathers over sons in this family that two generations seem to get warped: the son who should have been a soldier becomes an official, and the grandson becomes a soldier when he probably should have been pretty much anything else.

Carl Josef von Trotta follows his grandfather into the military. Is his life there honourable and meaningful? Is his fateful relationship with Dr Demant’s wife innocent?

His whole life in the military seems devoid of honour and meaning. He wants to live up to the memory of the hero of Solferino but never can. There are numerous details, such as his terrible riding skills, that show he’s in the wrong career.

The question about his relationship with Dr Demant’s wife Eva is interesting. I like that Roth left it ambiguous—I think that was an excellent authorial choice. The previous relationship with Frau Slama foreshadows this one and suggests that his relationship with Eva is not innocent. It’s clear, too, that Eva doesn’t love her husband and has been unfaithful to him before. And Carl Joseph’s long, empty, dry-mouthed silence when Demand confronts him is pretty damning.

So I doubt the relationship was innocent, but I’m glad that Roth left that possibility intact.

Strauss’s Radetzky March is heard almost as a refrain throughout this section. What is the significance of that?

It strikes me as a symbol of the gap between the old and the new, both in the empire and the family. In the old days, it was an expression of pride and a celebration of military achievement, but to Carl Joseph’s generation, it’s a relic of the past, played in peacetime by a small-town band to whom the notes are so familiar that “they could have played it in their sleep without a conductor.”

The image of the musicians playing The Radetzky March in their sleep is quite resonant, as is the idea of a band playing on without a conductor. Given what I know about the decay in the Austro-Hungarian empire of the time and the other references within the book, it seems like an apt symbol of this decline: an empty ritual stripped of its original meaning.

Roth may not judge his characters, but his sights are aimed at other targets: the social order and the military code of honour, for instance. How does Roth critique these?

It’s significant that the Trottas are a noble family because of a single random act that inspires the emperor’s whimsical grant of nobility. And this act is then misrepresented and disavowed by the “hero” himself.

This is how all aristocrats originally became aristocrats, after all. They did a favour for a powerful man and were rewarded with wealth and a title that got passed down through the generations. Usually these origins are old enough to be obscure, and all we see are the present-day manifestations, so I like the way in which Roth shows us the emptiness of these titles to which people pay so much respect. It’s a strong critique of the social order.

But that doesn’t stop the grandson from feeling entitled and accepting all the privilege that comes his way, including the privilege to duck out of the consequences of betraying his friends. He does nothing to prevent the death of Dr Demant, his best friend, and nor does anyone else, even though the outcome is obvious to them all. It doesn’t seem a very honourable code of honour.

Set in what was very much a man’s world, what do you think of the way Roth portrays the female characters?

None of them seem very fully developed so far. The women in the family die too early to have much of a role, leaving us with only a patriarchal lineage, which I think is deliberate because Roth is making a point about the distant, cold father/son relationships being like those of the emperor to his subjects.

As for the two women in Carl Joseph’s life, I don’t really understand their motivations. Frau Slama’s only role is to seduce the young Carl Joseph and then to die and provoke his guilt. Eva’s character could have been much more interesting as she is trapped in a loveless marriage. But although we get the tragedy of it from Dr Demant’s side, we never hear much about her frustrations, her feelings, her conflicts.

Do you have any further comments on this section?

I like the way in which death is embedded in the book in so many ways, and there are mentions of the Great War to come. The feelings of decline and decay are so tangible. And everyone seems to be tied to their fate and unable to change it. The death of Dr Demant, for example, was so pointless and avoidable, and yet nobody did anything or seemed able even to try to avoid it.

And yet, even though I suspect that things won’t end very well for young Carl Joseph, I am still very interested to see what happens. I think that’s quite an achievement by Joseph Roth: to tell us a story in which the trajectory is pretty clear from so early on, and yet to keep us (or me, at least) very interested in how things turn out. I’m looking forward to Part 2!

Update: I’ve now published my thoughts on Part 2 of The Radetzky March.

There are 8 comments

The book sounds so good and so rich. I an sorry that I could not join everyone for this event. The theme of fathers and sons as compared to monarchy and subjects seem particularly interesting. I also think it is interesting how major historical events fade into obscurity. I had barely heard about the battle of Solferino.

Yeah, it would have been great if you could have joined, Brian—I would have loved to hear your take on the book.

It’s interesting about historical events, isn’t it? My old Wall Street Journal editor used to make a point of saying “Remember the Maine” every time we passed the USS Maine memorial in New York City. His point, of course, was that nobody remembers the Maine, even though it was a huge event at the time and the phrase was a popular slogan to justify the Spanish-American War. And now millions of people pass it every day without even knowing what it signifies.

I felt the same about the opening. I had to reread it and felt like the book held me at arm’s lenght.

With hindsight, I might have answered the question about its living up to my expectations differently. There’s one element that struck me – the way Carl Joseph thinks of death but overall it is much drier than I remember it. I also forgot that it has hardly any female characters.

I skipped The Radetzky March question because I do so not like that music. But it’s a very fitting choice for this book.

I must say, you’re absolutely right – it does feel like a much older book.

Thanks for joining us.

Thanks for arranging it, Caroline! I love the format of having questions to answer—it gives the event a really nice focus and helps me to read more carefully and think about details that I’d gloss over in a general review. I got a little behind with reading other people’s posts because of work this week, but heading over to read yours now 🙂

Beautiful post, Andrew! I loved what you said about the relationship between fathers and sons, and about the origin of aristocratic titles. I loved the way how Roth depicts the evolution of the father-son relationship across generations, and how it tends to get better. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

Hi Vishy,

I thought I’d replied to this before, but I guess it didn’t go through. Or maybe my own site swallowed the comment 😉 Anyway, I love the insight about father-son relationships and how they tend to get better. I hadn’t really seen it that way before – they all seemed pretty awful to me! But the earlier ones are particularly awful, so I do see that there is some progress there 🙂

Love your insight on this book. I haven’t heard of it before but you definitely piqued my curiosity with this one. Will have to look into this book/author now. Thanks for sharing! 🙂

Hi Lashaan, Thanks for stopping by, and I’m glad your curiosity is piqued! It’s a very good read.