November is German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzy and Caroline! If you’re not familiar with it, it’s an annual celebration of literature in the German language. There’s a schedule of readalongs, but I’m too disorganised for that, so I’m going for the “read what you want, as long as it was originally written in German” category.

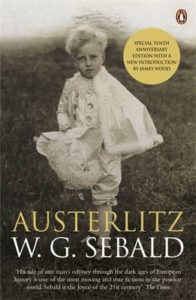

And what better book to choose than Austerlitz by W.G. Sebald, a novel that I have been meaning to read for so many years that I’d almost given up hope of unearthing it from the depths of my “to-read” list.

I’m happy to report that all the good things people have said about the book over the years, all those things that made me think “I must read Austerlitz one day”, are all true. It’s a beautifully written book that seems to meander around through digressions on architecture and fortress construction and yet, through these very meanderings, slowly builds a compelling story of a life reconstructed from the chaos and destruction of the Holocaust.

The novel’s title made me think of the famous Napoleonic battle, but it has nothing directly to do with that. Jacques Austerlitz is the name of the main character, a man who grew up in a small Welsh town, not even knowing his real name until his teenage years and not discovering his origins until much later. He was a small boy when his mother sent him away from Prague on a Kindertransport to Britain, and he remembered nothing of her or his journey until decades later, when he wandered into a waiting room at Liverpool Street Station and stood there for a long time, finding:

“scraps of memory beginning to drift through he outlying regions of my mind … memories behind and within which many things much further back in the past seemed to lie, all interlocking like the labyrinthine vaults I saw in the dusty grey light.”

It is from these scraps of memory that Austerlitz must recover the truth of his life. He does it in the same way that Sebald writes the book: slowly and with care, gradually accumulating details until something recognisable starts to appear.

And yet, although we follow Austerlitz on this powerful journey and learn a lot about him along the way, he still remains obscure and distant. I think part of the reason for this is the narrative structure. The book is narrated by an unnamed character who runs into Austerlitz at a station in Antwerp and then again years later, and he tells us about the story that Austerlitz tells him, which often involves stories that people have told Austerlitz.

So we get a distancing effect, with “said Austerlitz” appearing regularly throughout the book in an interesting device that reminded me of Tabucchi’s Pereira Maintains. And when we get stories within stories, the distance between us and the original narrator increases:

“From time to time, so Vera recollected, said Austerlitz, Maximilian would tell the tale…”

It sounds quite convoluted, but thanks to the skill of Sebald as a writer, the story is never hard to follow. He guides us through these shifting stories from different characters quite seamlessly, with the layers of story-telling adding to the obscurity of Austerlitz’s life but never losing or confusing the reader.

In fact, the descriptive writing is quite beautiful, and there are some wonderful insights not only into the darker pathways of European history but also into things like the nature of memory and the construction of identity and meaning. And the translation by Anthea Bell, who died just last month, is excellent.

I’d love to read more of Sebald’s work now. Do you have any recommendations?

There are 20 comments

Super commentary Andrew. This book has also been on my radar for a long time. It sounds very good. Thanks for recamending a translation. I find that seeking out a good one is important.

Thanks, Brian! I hope I’ve made it beep a little louder on your radar. I think you’d enjoy it!

This one sounds intense and intriguing. I, as a fellow bookworm, totally understand what you mean by unearthing from your deep to read list. Great post!

Hi Gayathri,

Yes, “intense and intriguing” is a pretty good description of this one 🙂 Ah, don’t get me started on the to read list. Mine is huge! I’m just happy that I actually managed to read something from it for once—usually I get distracted by new discoveries and read books that weren’t even on the list at all…

Lovely review. I’ve never read Sebald and am thankful for this introduction to his work. It’s a talented writer who can construct the distance you describe and still keep the reader interested and engaged. I also didn’t know it was German lit month; unfortunately I suffer from that neverending TBR syndrome that you mention, so I’m afraid I won’t get to one this month! Happy German reading to you though!

Hi Karla,

You’re absolutely right—that distancing effect really shouldn’t work at all. And yet somehow I kept following Austerlitz all the way through the novel, even though he remained obscure. And somehow the stories told by a minor character to Austerlitz and then to the unnamed narrator and then to us remained perfectly clear. It’s a real achievement! Maybe next year for German Literature Month 🙂

Great post. I especially enjoyed The Rings of Saturn

The Rings of Saturn is the fourth novel by W. G. Sebald I have read. I have now, for better or worse, read all his fiction. I wish very much there were more. I felt I somehow related to this work more than the others. Upon reflection I think this maybe because Sebald has such a unique narrative method that I needed come to understand.how to read his work.

This is a novel masquerading as an account of a walk about the narrator did in England. As he walks he reflects on the things he sees, his memories of historical events somehow connected to the path of his walk. To me it seems much of his thoughts were focused on cycles of corruption and decay hidden under something very different.

I found the Work entirely fascinating. I admit I was shaken up a bit by his reflections on sugar and art:

“In their heyday, said de Jong, the Dutch invested chiefly in cities, while the English put their money into country estates. That evening in the bar, we talked till last orders were called about the rise and decline of the two nations and about the curiously close relationship that existed, until well into the twentieth century, between the history of sugar and the history of art. For long periods of time there was little scope for an ostentatious display of accumulated wealth, and consequently the enormous profits that accrued to the few families who grew and traded in sugar cane were largely lavished on the building, furnishing and maintenance of magnificent country residences and stately town houses. It was Cornelis de Jong who drew my attention to the fact that many important museums, such as the Mauritshuis in The Hague or the Tate Gallery in confectioner to the Viennese court, which Empress Maria Theresia, so it is said, devoured in one of her recurrent bouts of melancholy.”

Sugar plantations employed huge numbers of slaves. Under brutal conditions, the average life expectancy of a slave was two years. The great art of Europe arose from this misery. I saw the cosmic truth in this. Beauty, art, culture, great treasures, magnificent buildings in London, Amsterdam arose from misery. I wondered how this connects to Literature.

Hi Mel,

Thanks for visiting and for sharing your thoughts on The Rings of Saturn. That’s actually the Sebald novel I was thinking of reading next, so it’s good to hear that you related to this one the most. Thanks for the quote. You’re right, it’s quite shocking to think how much of European art resulted from the misery of slavery. I remember years ago reading Capitalism & Slavery by Eric Williams and being horrified by just how much of the wealth I grew up with all around me in the UK came directly or indirectly from sugar and slavery. Review here if you’re interested: https://andrewblackman.net/2012/11/capitalism-slavery/. Anyway, thanks for making these points. And I look forward to reading The Rings of Saturn!

Yes, I have recommendations: all of it. Possibly saving the poetry for after the fiction and criticism. Austerlitz is the most conventional, the most novel-like, of Sebald’s novels, for what that is worth.

Thanks, Tom! It’s interesting to hear that his final novel was his most conventional. I look forward to exploring the rest.

I, too, have long seen this book and meant to read it. Alas, I haven’t yet. But, I am encouraged by the way you tell me that he is slowly uncovering the truths of his life (something which doesn’t seem necessarily tied only to the Holocaust, in my mind). I love novels which are a search of one’s identity; it seems we have much to find out about the world and ourselves which is never quite fully revealed.

Yes, you’re absolutely right, Bellezza! The novel does have a much wider resonance. Being a child refugee from the Holocaust gives Austerlitz a more obvious reason to search for his identity than most, but I agree that we all have so much to discover, much of which we can only glimpse. Finding out who we are, where we fit in and why we’re here is such fertile ground for literature. Thanks for bringing out that aspect of the book, which I didn’t get across very well in the original post! If you do read Austerlitz, please come back and let me know what you think.

What a wonderful pick for this event! Like you, I’d had this one on my TBR for years and, like you, I finally read it this year. But earlier, and all of them, at the rate of about one/month. It was a fantastic reading experience and I highly recommend it. Afterwards, I checked the library catalogue and found a lot of essays and photography books on/about his work which extended the project yet again. I know you’re on the move, but perhaps because you’re in Europe you would have even more likelihood of finding sources in a library to begin with.

Hi B.I.P., That sounds wonderful! Maybe some Sebald immersion is just what I need.

You’re right about finding sources here, but unfortunately one of the hard things about travelling around Europe is finding so many great libraries and bookshops and knowing that I won’t be able to read most of the books in them. I have a fantasy of being a hyperpolyglot and reading all sorts of languages, but in reality, although I can say “Hello” and “Thank you” in about 25 languages, I can only read books in French and German, and then only very slowly and painfully. So I spend more time than I’d like on my Kindle instead. Right now I’m in Greece, and I can hold some basic conversations in the language, but can’t get close to reading essays on W.G. Sebald 🙁

Sebald is wonderful. A good follow-on from Austerlitz is probably The Emigrants (one of my favourite books of all time). It’s sort of non-fiction, tracing the biographies of four Jewish emigrants, but it’s an incredibly moving story of life in exile.

Hi Marina Sofia, Thanks for the recommendation! The Emigrants sounds wonderful. I’m looking forward to reading more Sebald!

Read them all again and again. All his books

Thanks, Iliana! That’s a strong endorsement to go with the others in this comment thread. I think I’ll end up following your advice!

Very interesting review, Andrew.

I started this book and liked it so much that I put it aside and then never returned to it. That said, it’s a very difficult writer in German, even for a native speaker like me. I compared the original with the English translation and must say, it flows more in English. He’s very unwieldy in German. The English translator made a choice – readability in lieu of staying true to the original. I get it. A literal translation in English would have been a disaster as he can even be grammatically wrong.

Ah, that’s very interesting to hear, Caroline! It did seem to flow very well in English, even with the long sentences and multiple layers of attribution. From what you’ve said, I am very grateful to Anthea Bell for sparing me some of the unwieldiness 🙂 It’s quite a bold move for a translator to make such a change to a writer’s style.