Although in her previous novels Aminatta Forna has grappled with wars and atrocities in Sierra Leone and the former Yugoslavia, her latest novel, titled Happiness and set in the heart of London, may be her most challenging undertaking yet.

Although in her previous novels Aminatta Forna has grappled with wars and atrocities in Sierra Leone and the former Yugoslavia, her latest novel, titled Happiness and set in the heart of London, may be her most challenging undertaking yet.

After all, happiness is often as elusive as the foxes and coyotes that slink across the pages of Forna’s novel. It is wild and untamed; it doesn’t play by our rules. Try to capture it by working hard or following your dreams or buying the latest iPad, and it will likely slip away. Turn your back, and it might just sneak up on you in the unlikeliest of places.

A woman bumps into a man on Waterloo Bridge. It’s a fleeting encounter, but then they keep meeting again. They discover each other: Attila the Ghanaian psychiatrist and Jean the American wildlife biologist. Their lives slowly intertwine. It’s a classic romance plot. Will they? Won’t they? Of course they will.

But this is not the sort of happiness that Happiness is really about. Forna is trying to get at something more complex: why ishappiness so elusive? Why are some people unhappy when they have everything, while others seem to be happy in much harsher circumstances?

To answer this question, she builds up a complex and fragmented plot involving not only the slow-burn romance between Attila and Jean but also the wrongful detention of a young Ghanaian woman, the search for her missing son, the slow decline of Attila’s former colleague and lover from early-onset Alzheimer’s, and much more. To add to these multiple threads, there are flashbacks to everything from the sudden death of Attila’s wife in Accra to his former driver’s kidnapping in Iraq and a wolf hunt in nineteenth-century Massachusetts.

Forna’s London is a city of outsiders. Jean and Attila are joined by a supporting cast of traffic wardens, street sweepers, security guards and doormen from across Africa, as well as a Bosnian who works as a Savoy chef by night and a silver-painted street performer by day. Then there are the ultimate outsiders: the wild animals like urban foxes and parakeets that, having moved from a place where they couldn’t survive to one where they thought they could, now find themselves targeted for extermination in the name of safety.

What all these disparate subplots and minor characters have in common is that they help to build a picture of happiness and how it might—or might not—be attained.

One logical way to pursue happiness would be to remove or avoid things that lead to unhappiness. Yet the characters in the novel who try that approach don’t fare too well. The parakeets, after having their eggs addled and their tree cut down due to complaints of noise and damage, simply relocate and survive elsewhere, leaving the angry denizens of Twitter and radio talk-shows to find new targets. One of Jean’s rich clients in her garden design business seems to have insulated herself from everything that could make her unhappy, and yet what is left is certainly not happiness, but a numbing existence behind glass in her chic City Road apartment, worrying a cuticle with her teeth, afraid to make even the simplest decisions.

If happiness cannot be achieved by subtracting unhappiness, what is the alternative? The answer lies, perhaps, in another book with an ambitious one-word title, Resilience, by the French psychiatrist Boris Cyrulnik—a book which Forna reviewed for The Daily Telegraph in a 2009 article that now reads like the novelist’s early draft for the central themes of Happiness. What makes some people resilient while others succumb to trauma, Cyrulnik argues, is not so much the experience itself as the way people frame it.

Attila comes to a similar conclusion, telling his audience at a conference lecture that psychiatrists have unwittingly divided the world into those who have suffered, who must necessarily be traumatised, and those who haven’t, who should be normal. The trauma victims are left with no hope of recovery, while those on the other side of the divide desperately try to cleanse their lives of contact with suffering and wonder why they’re not happy. They are doomed to ‘face the void without ever knowing the reality of life’, forever trapped in ‘the creeping numbness that the fear of suffering, the terror of pain has created.’

In an age of Brexit and the refugee crisis, of climate change and deepening inequality, Forna’s novel is a timely reminder that building higher walls will simply leave us like Jean’s client, biting our nails behind glass, terrified of the suffering outside. We may all have a better shot at happiness if we open the doors and bravely face the void alongside the Sierra Leonean traffic wardens and the Bosnian street performers—and perhaps even the foxes and the parakeets too.

If you enjoyed this post, check out my review of Aminatta Forna’s earlier novel The Hired Man for Puritan Magazine. Or click here to discover other books I’ve reviewed.

There are 2 comments

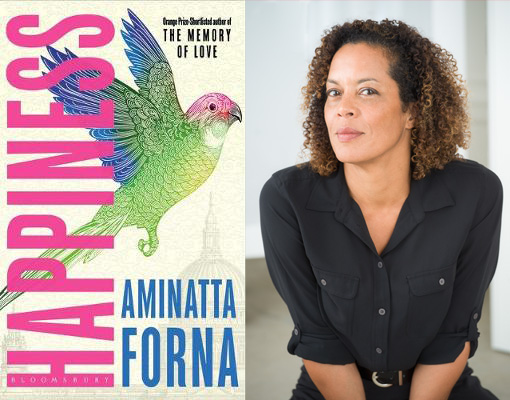

Ooh, I like the sound of this one! And bonus, the cover is pretty too!

Yes, I think you’d like it, Stefanie! The cover is eye-catching, isn’t it? One of the things I don’t like about reading ebooks is that I don’t get to appreciate beautiful covers. I only really noticed this one when I was putting this post together!